Grain markets started the new year in desperate need of a lifeline, with corn futures making new contract lows and soybeans breaking decisively to their lowest level since the end of June. But history suggests a helping hand from a series of big Jan. 12 reports from USDA is anything but a sure bet, threatening sluggish trade into spring.

The big government data dump to kick off 2024 includes final monthly production estimates for 2023, Dec. 1 grain stocks and updated World Agricultural Supply and Demand forecasts for the current marketing year, as well as U.S. winter wheat seedings. Any, all, or none of the reports could reverse futures higher – or trigger another leg move down.

Here’s what to look for from what’s traditionally one of the most closely watched events of the year.

Yield is key

The size of 2023 crops sets the table for the number buffet at the end of the week. USDA hasn’t changed its acreage prediction for either crop since September, when planted and harvested estimates for both crops increased, so changes could be overdue. Otherwise, any modifications to production must come from yields, which also went up in November, though the 174.9 bushels per acre corn and 49.9 bpa soybean prints were still below long-term trend readings for “normal.”

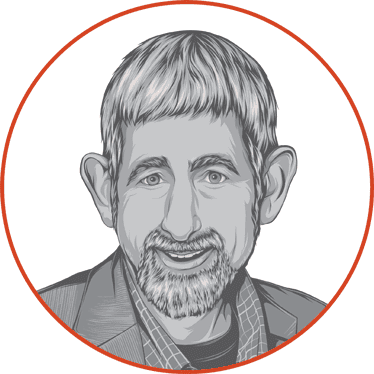

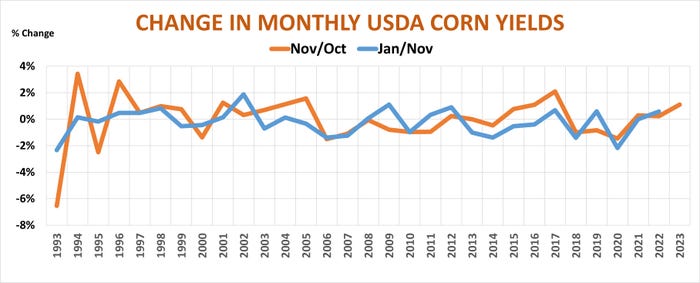

January yield changes are pretty much a toss-up historically. Over the past 30 years USDA increased its corn and soybean yields in January 14 times, and the correlation between November and January estimates is near-perfect. Still, increases in November don’t necessarily mean another boost in January. Indeed, average yields for both crops are actually a little lower in January compared to November.

So, statistically, odds for January changes are anything but a done deal.

Huge yield revisions, while more common in November, are also less likely in January. Corn changes tend to be 2% or less while soybeans move in a band of 1% up or down.

Price moves

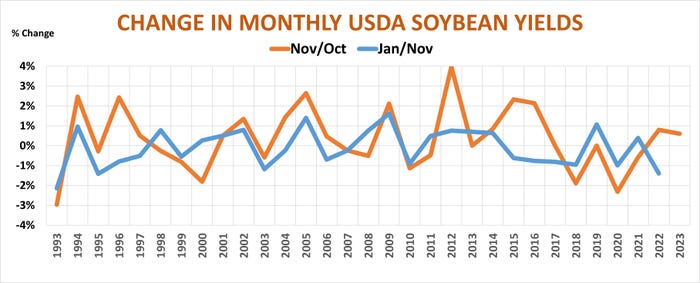

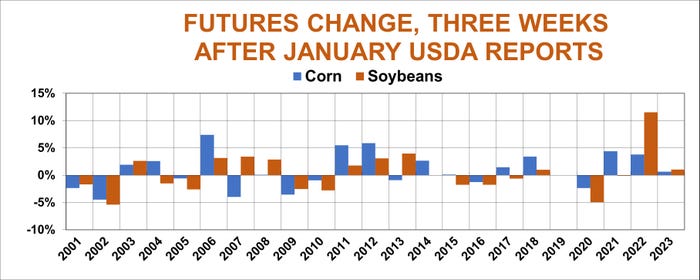

Despite the somewhat small changes for yields in the past, these January reports have a reputation for big surprises. While report day price moves recently were 2% or less, changes two and three times greater than that occurred before the U.S.-China trade war emerged in 2018, particularly for soybeans.

And sometimes the report day changes are a head fake for markets focused elsewhere. That was the case in 2022. Futures gained 5.5 cents the day of the January report, despite a cut in the production estimate for Brazil. The market paid attention to that soon enough, gaining $1.62 over the next three weeks.

Overall since 2001, corn went up 12 times immediately after the numbers came out, with soybeans gaining 13 years. After three weeks corn was higher 13 years, but soybeans were up only 10 times, a reminder that rallies can quickly fade, too. And as the charts demonstrate, most years the markets keep to a 5% band, higher or lower, though at last week’s prices that translates to 25 cents for corn and 65 cents for soybeans – nothing to sneeze at.

Surprise, surprise

Of course, what matters to traders in the wake of USDA reports is not necessarily what the government says, but what the trade thought it would say – the average guess in the market. This is perhaps most true for Dec. 1 grain stocks, which seem to be harder for today’s newbie traders to understand.

The size of the 2023 crops are the starting point for these calculations, which represent how much was used from September through November, the first quarter of the marketing year, after imports and leftover supplies are added to production.

Soybeans should be the easiest to figure because the vast majority of usage is pretty well already known from previously data on exports and crush. But surprises still come from another category, called residual usage, which USDA uses in part to correct misfires from previous reports. Residual use normally isn’t large – USDA put it at 26 million bushels in December for the 2023 crop. Sometimes it can be much bigger, and some quarters it’s actually a negative number.

The biggest cause for discrepancies tends to be production that was substantially different from USDA’s January estimate. The agency typically doesn’t issue its “final” production estimate until after the marketing year closes Sept. 1, the data that comes out at the end of September.

Quarterly corn stocks are harder to estimate because so much of the crop walks off the farm after being fed to livestock. So, residual corn use is folded into the government’s feed total, which can never be precisely known, while consumption by exporters and industries like ethanol plants is reported weekly and monthly.

With that said, assuming no change in production, Dec. 1 corn stocks should come in around 12.2 billion bushels, the most since 2017. Soybean inventories near 2.9 billion could be the least since 2016.

The future?

The final corn and soybean data Jan. 12 comes from USDA’s update to the WASDE, including usage, ending stocks and average cash prices for the crops.

Assuming no change in production, corn stocks at the end of the marketing year could go up from the 2.131 billion USDA printed in December. The biggest question is ethanol, where the agency sees corn demand gaining 150 million bushels over the 2022-2023 marketing year.

Strong processing margins in the first quarter helped boost corn apparently used by plants even better than USDA’s forecast, with December consumption the best in two years. But returns plunged back into the red at the end of 2023 as inventories grew, burdened by fairly steady cash corn costs and falling ethanol prices. In contrast to USDA, the U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts lower ethanol production due to falling blender demand. What happens to crude oil likely will spell the difference, depending on Red Sea shipping disruptions, Chinese demand, and the ability of OPEC and its allies to maintain production cuts.

USDA forecast soybean ending stocks at 245 million bushels in December, a total that could hinge on export demand. While sales and shipments so far are down from last year, the current pace translates into better demand than the official outlook, which could trim the final number depending on Chinese demand and how crops turn out in South America. Rains boosted yield hopes last week and the latest sales data put total U.S. commitments to China down 25% from last year at the end of December.

Wheat wild card

A big surprise from winter wheat seedings could also conceivably spill over into corn and soybeans. If farmers sowed fewer acres than anticipated it could free up more ground for corn and soybeans next spring, impacting 2024 crop prices and dragging old crop lower.

Seasonal trend factors aren’t encouraging. The break in old crop corn to new lows puts that market squarely in line with the pattern from years when production wasn’t terribly bad. If that trend holds, futures could struggle just to get back to fall highs, though even that would be an accomplishment. The best hope for a rebound could come from big speculators buying back bearish bets, after pushing their net short position to its most negative reading since June 2020.

Old crop soybeans are also on a downward trajectory. In similar years futures did well just to get back to December highs. This year that would represent a rally of a buck a bushel, nothing to sneeze at, though funds are still a very long ways from the big short positions they held during the trade war.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like