By Kim Chipman and Jennifer A. Dlouhy

After decades of battling against more ethanol going into U.S. cars, Big Oil is joining Big Agriculture in a push to expand use of the corn-based biofuel.

The longtime foes are increasingly finding common ground as the growth of electric vehicles threatens to slash gasoline demand. Fossil-fuel giants are also ramping up investment in renewable fuels in a bid to capture government incentives aimed at cutting emissions and curbing climate change.

“Today’s a different world,” said Bruce Rastetter, founder of Summit Agricultural Group. “It’s a whole sea-change of oil companies working with the biofuels industry to decarbonize the gas tank.”

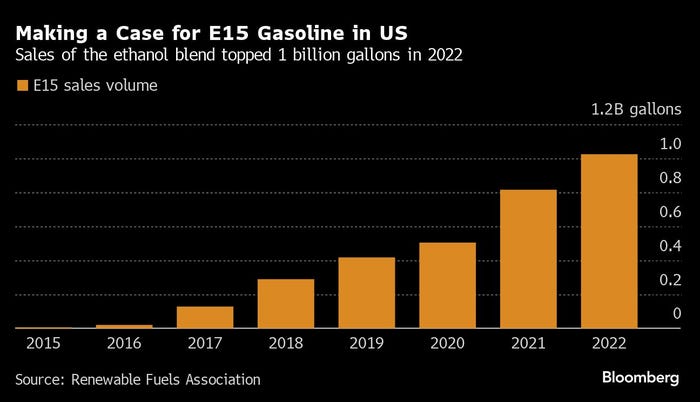

Most of the gasoline sold nationwide contains 10% ethanol, known as E10. But selling higher blends of 15%, or E15, through the summer months is generally off limits without a waiver from the Environmental Protection Agency.

The American Petroleum Institute — the powerful oil lobby — is uniting with the National Corn Growers Association and other groups to support a bipartisan measure from Republican Senator Deb Fischer of Nebraska that would allow year-round sales of E15 across the country. The legislation would also preserve access to lower blends.

The collaboration is the biggest so far between the two sides, and is changing the face of energy lobbying on Capitol Hill as they fight for liquid renewable fuels.

“We’ve been shoulder-to-shoulder on this,” said Will Hupman, API vice president of downstream policy. “Historically, that hasn’t been the easiest thing to do.”

Combative History

America’s petroleum producers have been at odds with farmers since the days of the Model T, when Henry Ford declared ethanol — the alcohol found in wine, beer and liquor — the fuel of the future. But oil magnate John D. Rockefeller and the Prohibition era set a different course for the automotive industry.

The U.S. government began to encourage the use of ethanol in the late 1970s following the oil crisis, when President Jimmy Carter tasked agribusiness leaders to produce ethanol as a way of reducing petroleum dependence. Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. started output in 1978. After the 2001 terrorist attacks intensified energy security concerns, Congress established a mandate compelling ethanol and other biofuels to be mixed into the national fuel supply each year.

That has sparked an ongoing debate, with oil producers arguing that blending brings higher refining costs, putting labor union jobs at risk and increasing prices at the gas pump.

It also has spurred clashes over pollution tied to summer driving. A federal clean air law blocks E15 sales in most of the U.S. from June through mid-September, when summer heat boosts evaporation, increasing the possibility of smog from all gasoline.

But the rise of electric cars is set to curb both liquid fuels, bringing oil and farm groups closer together.

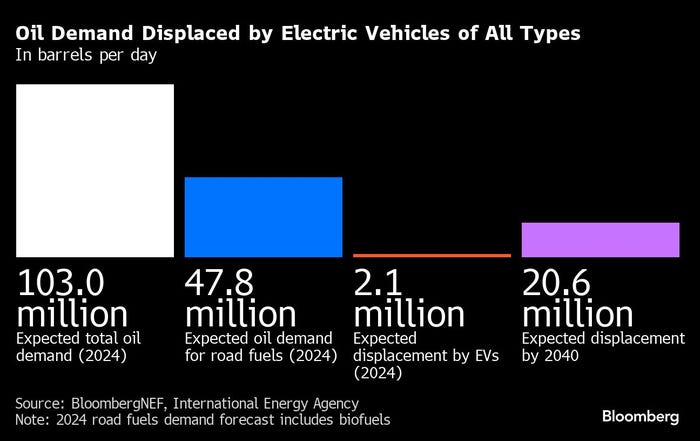

The Biden administration has set a target for half of all U.S. vehicle sales to be electric by the end of the decade. While electric cars so far haven’t made a major dent in global fuel demand, BloombergNEF estimates the displacement of oil consumption by EVs will increase to more than 20 million barrels a day by 2040.

Ethanol backers such as Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack are pushing biofuels as a significant weapon to help slash carbon emissions, noting that it will take decades or more for America’s passenger-car fleet to be entirely electric.

Corn growers say the administration’s approach to climate change is “short-sighted” for prioritizing electric vehicles over biofuels, according to a statement released on Wednesday.

“If we are going to address climate change and meet our climate goals, we are going to have to take a multi-pronged approach that includes tapping into higher levels of biofuels,” according to a letter sent to President Joe Biden on Wednesday.

API and other oil groups see the Fischer bill bringing long-term certainty to the marketplace while avoiding potential supply disruptions and upheaval posed by another approach.

That alternative path, offered by Midwestern governors, would force the EPA to apply air-pollution requirements evenly to E10 and E15, allowing full sales of the higher blend but effectively compelling a boutique, less-evaporative fuel in those states. The Biden administration is on track to approve the change within months, despite concerns it would create an uneven patchwork of rules and require the construction of costly new infrastructure.

Along with API and the corn growers, support for Fischer’s bill stretches across the political spectrum. The coalition includes the Renewable Fuels Association and Growth Energy, as well as various farm organizations and groups representing fuel marketers and truck stops.

“This is the first time I can remember in 20 years where all of these stakeholders have come together and actively lobbied in support of a common interest,” said Geoff Cooper, head of the RFA.

Still, the effort faces significant hurdles, including resistance from independent refiners more exposed to biofuel compliance costs. The Fueling American Jobs Coalition that represents union workers and independent oil refiners wants to pair year-round E15 access with caps on the cost of credits used to fulfill annual biofuel quotas. The current bill would only enrich large, integrated oil companies at the expense of merchant refiners, it says.

The measure does have the backing of some oil-state legislators including Senator Roger Wicker of Mississippi, a Republican who was among lawmakers fighting to limit ethanol blends to 10% in 2013.

Brooke Appleton, vice president of public policy for the National Corn Growers Association, said if their effort is successful, she’s hopeful the oil and farm groups can join forces on other issues. “We have a lot more in common than we probably thought we did.”

© 2024 Bloomberg L.P.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like