January 20, 2017

Think Different

Weed scientists were surprised by both the dramatic increase of Palmer amaranth identified in Iowa last year and by its cause for expansion (contaminated native seed mixes from out of state). Indiana, Ohio, Illinois and Minnesota also reported contaminated seed issues, but to a lesser degree. While native perennial vegetation in these conservation plantings should smother Palmer amaranth over a period of a few years, the concern is that it may spread into neighboring crop fields.

Stopping the spread of this aggressive pigweed relative of waterhemp is unlikely in Iowa and other Midwest states, but how it moves into new fields can be limited. Farmers with newer conservation plantings in particular should learn to differentiate Palmer from waterhemp and other pigweeds, as it is critical to prevent its spread.

-----------

When Iowa State University weed specialist Bob Hartzler crested a hill on a Crawford County road last summer, he saw a grassy field in the distance covered with dark green specs. At first glance, he thought a CRP field had been overtaken by volunteer red cedar trees.

But as the photos show, he discovered that the four- and five-foot tall, bushy green plants were Palmer amaranth, the dangerous pigweed species that has decimated cotton, soybean and corn fields in the South. He witnessed one of the first infestations of what would become many conservation seed mix plantings across the state that were contaminated with Palmer weed seed.

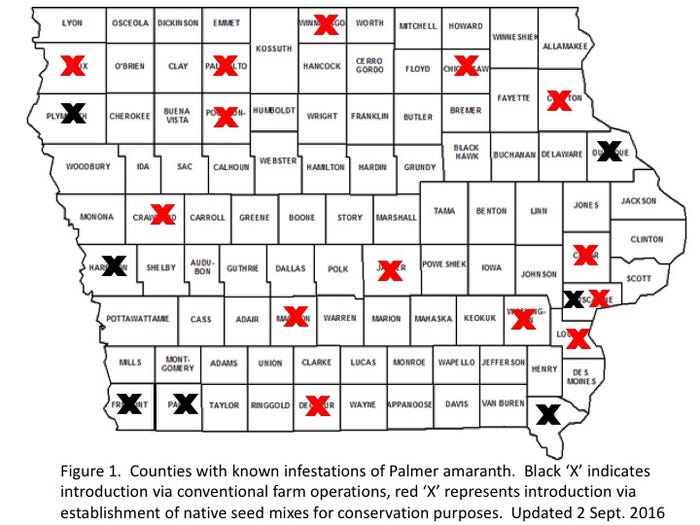

“We were surprised by both the dramatic increase of Palmer amaranth infestations in Iowa in 2016, and by the primary means of introduction,” Hartzler says. “Before 2016, only five counties were reported. At the end of October last year, Palmer amaranth had been confirmed in 46 counties, and we believe it’s present in many more, maybe all counties in the state.”

Six of the confirmed discoveries were associated with traditional livestock or crop practices, but the most prevalent source was conservation plantings.

More than 100,000 acres were planted with native seed mixes in Iowa in 2016, Hartzler explains. Many counties had between 100 and 200 fields entered into CRP programs like the pollinator habitat program. Iowa native seed producers couldn’t meet the demand for seed, so they imported seed from other states. Seed came from Texas and Kansas, two states with Palmer amaranth problems.

Tough to eradicate now

“It was inevitable that we’d find more Palmer amaranth in Iowa,” Hartzler says. “But with its introduction into so many counties through seed mixes, we are beyond eradication. We need to limit new introductions and limit its impact now.”

He says a first step is to prevent new introductions, by purchasing locally produced native seeds and being wary of using feed or bedding from states to the south. Hartzler also stresses early detection and eradication in high risk areas such as conservation plantings.

“Owners of the conservation plantings may not even know they have a problem,” Hartzler says. He took the unusual step of filing a Freedom of Information Act request to obtain the names and addresses of land owners who had contracts to seed native mixtures on conservation land last year. His purpose was to alert them to the potential problem, and advise them on steps they could take.

“There’s little flexibility from USDA in managing Palmer amaranth in conservation plantings,” Hartzler says. “Mowing and weeding by hand are the two options available. Mowing won’t kill Palmer amaranth, but it will reduce seed production. It will be critical to limit seed movement from those plantings to other fields. One practice is to limit traffic in conservation plantings, especially late in the year when seeds are on the plants.”

Palmer amaranth is not likely to persist in native grass plantings over time since annual weeds are at a big disadvantage with perennial plants. But native perennials are slow at establishing, and the Palmer amaranth will be able to produce large quantities of seed in the initial years of establishment. This provides the opportunity for Palmer amaranth to move into crop fields.

Scout and identify

The key to minimizing the damage of Palmer amaranth in Iowa and other Midwest states is for everyone involved in production agriculture to learn how to differentiate Palmer amaranth from waterhemp and other pigweeds, Hartzler says. “We all need to be observant. It could easily be overlooked in crop fields because it looks so similar to waterhemp.”

Palmer amaranth is a big concern compared to other weeds because it has proven an ability to resist herbicides, grows very quickly and is very competitive. “There is no evidence Palmer amaranth is any more adept at evolving herbicide resistance than waterhemp,” Hartzler says, “but it’s clear that uncontrolled Palmer amaranth is more damaging to crop yields than other weedy pigweeds because of its growth habits.”

The history of Palmer amaranth is that its initial rate of spread is relatively slow for 20 to 30 years, but then the weed spreads rapidly and dominates the landscape. Once a weed establishes a permanent seedbank it becomes economically unrealistic to eradicate. Hartzler says “it would be a shame to miss this opportunity to stop Palmer amaranth from becoming a dominant weed in the state.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like