August 22, 2023

If herbicide-resistant tall waterhemp is a problem in your soybeans, Bryan Brown has some science-based data that could help you manage this persistent weed.

Brown, who is with the New York State Integrated Pest Management program, got a grant from the New York Farm Viability Institute to evaluate different approaches to waterhemp management. He conducted field trials with eight products applied, either alone or in combination, and tested the use of cereal rye residue as a suppressive mulch.

“Programs that included at least two non-chemical tactics or herbicides from Weed Science Society of America [WSSA] groups 4, 14 or 15 were very effective in the trial here,” Brown says.

But he notes that waterhemp has developed resistance to groups 4 and 14 in other states. Those groups include dicamba, 2,4-D, Valor and Cobra, and he adds that groups 2, 5 and 9 herbicides should not be relied on for waterhemp control.

Brown’s main trial was planted on a field of Odessa silt loam soil where waterhemp had survived various herbicide applications, produced seed and was moderately controlled in corn. Preemergence treatments were applied after planting soybeans.

Postemergence treatments or cultivation were conducted midseason. Weed control was assessed about eight weeks later.

Waterhemp was the dominant species in Brown’s two-year trial. Additional trials were conducted by Venancio Fernandez of Bayer Crop Sciences; Cornell Extension field crop specialists Mike Hunter and Mike Stanyard; and Cornell agronomy specialist Jeff Miller.

Other species did not provide enough data for comparison. Soybean yield was measured in mid-October.

Two modes needed

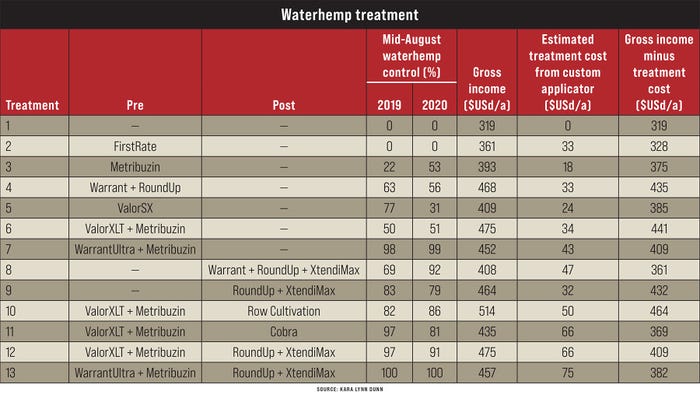

Comparing a control and 12 treatment plots, the trials showed that at least two effective modes of action — in this case, groups 14 and 15 — were necessary for successful control. The gross income in the table that follows was calculated by multiplying average yields for the three site years by a soybean price of $10.05 per bushel:

“Two-pass programs were generally more effective than pre- or postemergence-only programs, reducing the burden on each pass,” Brown explains. “If conditions are not optimal in one of the passes, the other pass can help ensure successful control is still achieved. While this approach is generally more expensive, including more diverse chemistries and/or non-chemical tactics can help reduce the risk of worsening the waterhemp resistance problem.”

High yields seen in a treatment that included row cultivation were probably because of increased soil aeration and nutrient release. However, Brown notes, “Due to the small plot size of our trial, there was some variability in yield results due to random chance.”

Cereal rye residue helps

Brown got cereal rye residue from a nearby field to test as a suppressive mulch.

The residue was immediately applied to the trial plots at rates of 7,140 and 3,570 pounds per acre, both considered attainable in New York state with or without fertilizer. A control plot received no residue.

Used alone, the cereal rye applied at 3,570 pounds per acre provided an average 83% control compared to the untreated check plot. The 7,140-pounds-per-acre application provided an average 87% control, suggesting that its use in conjunction with a moderately effective herbicide program could provide excellent control.

“The level of control achieved with cereal rye residue alone may be sufficient to avoid soybean yield loss. However, in conjunction with an herbicide that provides only 92% control used alone, applying rye residue at the higher rate could provide the opportunity for 99% control of waterhemp,” Brown says.

Don’t let waterhemp set seed

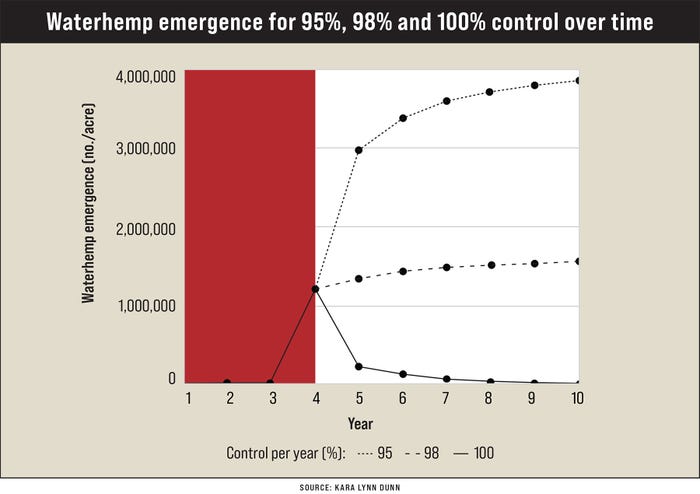

A 10-year model of waterhemp emergence was developed using a number of seeds in the soil of the trial plots.

The following assumptions — based on the work of Vince M. Davis, Joseph M. Heneghan, William G. Johnson and colleagues at Purdue University — were factored into this model:

A three-year period of uncontrolled waterhemp growth after waterhemp emergence year.

8% of the seedbank would emerge each year.

For a given cohort, viability would reduce by 81% after one year, an additional 50% in years two and three, and by 32% each subsequent year.

The seed bank modeling showed that control at 95%, 98% and 100%, respectively, would cause the waterhemp emergence to increase, maintain or decrease over time.

“Our modeling shows that programs that control waterhemp 100% can result in greatly reduced emergence in subsequent years, whereas programs that achieve 98% control or less will perpetuate the problem,” Brown says.

Although 95% control would likely avoid a crop yield loss, the resulting waterhemp seed production and increase in emergence in subsequent years would likely make successful control increasingly more difficult over time.

“The results we see from the trial farm location in New York’s Finger Lakes region are likely applicable statewide,” Brown says.

For more information, call Brown at Cornell AgriTech in Geneva at 315-787-2360 or see nysipm.cornell.edu. Brown reminds growers to read the labels of any products being applied prior to use.

Dunn writes from her farm in Mannsville, N.Y.

Read more about:

WaterhempAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like