March 15, 2024

Despite pressure to produce more food in an increasingly difficult climate, only 27% of U.S. farmers and ranchers have adopted precision agriculture technology, according to the Government Accountability Office’s latest assessment on farm technology’s benefits and challenges.

According to the report, these are the percentages for technology used nationwide:

Automated guidance systems were used for 58% of corn acres and 54% of soybean acres.

Yield mapping was used for planting 44% of both corn and soybean crops.

Variable-rate technology was used for 37% of corn and 25% of soybeans acres.

Farmers who use precision technology increase profits and reduce fertilizer and herbicide use, says the report. They also consume less fuel, save water, and prevent excessive chemical and nutrient runoff.

Yet, hurdles to adoption include a lack of standards, data sharing concerns and high upfront costs.

“To get into precision ag, equipment is very expensive,” says Brian Bothwell, a director in the GAO's science, technology assessment and analytics team, and author of the tech report.

“If [the farmer] doesn’t buy from the same manufacturer, he might have pieces of equipment that don’t talk to one another,” he says. “They’re different. They’re not interoperable. It’s not easy or cheap to swap one of them out.”

The January report broadly defines precision technologies to include emerging machines such as drones and ground robots. Other technologies include in-ground sensors, targeted sprayers and automated mechanical weeders, as well as more established tech like automated guidance systems.

Different crops

The seemingly low nationwide adoption rate for precision tech could be related to the diversity of U.S. crops.

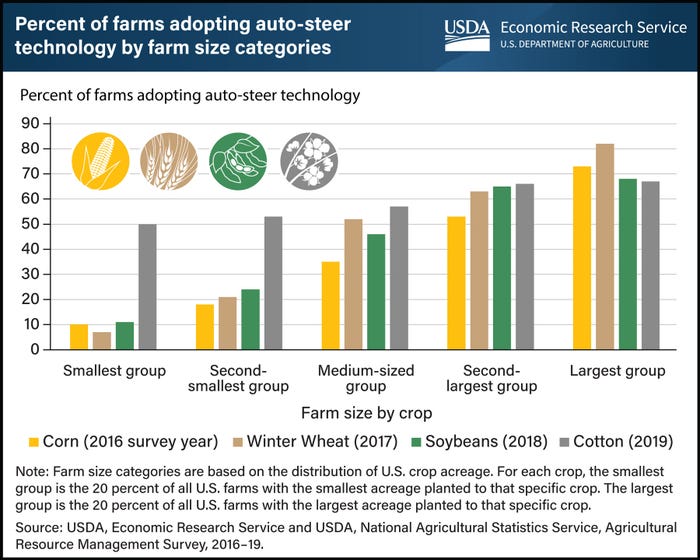

“If you look at the cost of technologies for cotton, they tend to be higher than the costs for soybeans,” says Jonathan McFadden, a research economist at USDA’s Economic Research Service. “Adoption rates vary considerably.”

According to the USDA’s most recent report on precision agriculture adoption, which McFadden helped write, yield mapping was used for 5% of soybean-planted acres in 1996. That rose to just under 45% in 2018. The adoption rate was similar for corn. Likewise, less than 5% of corn acres were planted using autosteer in the late 1990s but rose steadily. Now, half of the planted land acres for these crops is managed by autoguidance.

Due to higher costs for plant-specific precision technology, crops like winter wheat, rice, cotton and sorghum have been slower to adopt new technologies.

U.S. farms are adopting precision technologies at different rates, with the largest farms adopting autosteer guidance technology at significantly higher rates.

There’s also a stacking effect. Some farmers use more technology than others because basic technology like soil mapping is necessary to implement advanced systems such as variable-rate applications.

“It’s well known that farmers who are using variable-rate technologies tend to do so because they have soil analysis. They have soil maps,” McFadden says. “Farmers are using [data-tracking] technologies after that. One could think of that as a precondition.”

This seems to be the case for R.D. Offutt Farms of Fargo, N.D. From its inception in the early 1960s, the family-owned farm has embraced technology to maximize yields in sandy soil.

“We are committed to investing in soil health, conserving water, and keeping the food supply safe and stable,” says Jennifer Maleitzke, the farm’s director of communications and external affairs.

Over the years, Maleitzke says this mindset has helped them increase efficiency and environmental sustainability while producing higher yields. They use precision technology throughout operations, including soil mapping, variable-rate fertilizer application, spray boundaries using John Deere’s iTEC Pro software, soil moisture monitoring, and ultrasonic flowmeters to conserve water.

“We still used tried-and-true methods, such as digging both shallow and deep holes in the soil to allow us to directly check potato growth and soil moisture. However, we are also using more advanced technologies to better understand soil moisture levels, when irrigation is needed and to ensure accurate water use reporting,” Maleitzke says.

Crop variance might explain why farms in certain states use more technology than others. More than half of farms in North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa and Illinois employ precision agriculture technologies like variable-rate fertilizer applications and yield monitoring, according to the GOA report.

In California and Kansas, 40% to 49% of farms use precision technology, as do 30% to 39% of farms in Michigan, Minneapolis, Indiana, Ohio, Utah, Tennessee, Louisiana and Wyoming. Only 10% to 19% of farms in Wisconsin use precision tech.

Farm size correlation

The study revealed that precision adoption rises with farm size. “If you’re farming 10,000 acres, and you buy this widget that costs $2,000 and use it across your farm, the cost per acre is relatively low,” says Bruce Erickson, clinical professor of digital agriculture at Purdue University. For a farmer working 500 acres, “that’s a lot of money.”

Because of economies of scale, Erickson believes smaller farms are losing out on adopting this valuable technology. “With precision farm [technology], there’s more of a scale advantage,” he says. “The thing my colleagues worry about is the small farmers in Asia and Africa. They’ve pretty much been left out of this digital revolution.”

Ease of use

Complexity also determines adoption. Autoguidance systems, for example, are easily understood and widely used. Bothwell says this is because they don’t have a steep learning curve.

Based on Erickson’s annual survey of equipment dealers, most farmers use guidance and have a yield monitor, and use planter controllers and sprayer protection controllers that turn on and off. Comparatively, “less than half of farmers are doing variable-rate pesticides, versus nutrition, versus seeding rates,” he adds.

The GOA report agrees with Erickson’s assessment. Technologies that are relatively easy to use are adopted more quickly. Conversely, the report finds “data-intensive technologies that require farmers to collect, collate, analyze, and respond to data have a higher barrier to entry and are less widely adopted.”

Demographics are another notable variable. The report notes younger farmers tend to adopt precision agriculture technologies faster than their older counterparts. (According to the 2022 census the average age of a U.S. farmer is 58.1 years old.)

Read more about:

PrecisionAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like