Since the first mosquito left its itchy mark on ancient man’s ankle, since the first weevil infiltrated a jar of stored grain, humans have been battling pests with every tool they can devise.

Now, Kansas State University experts are bringing nanotechnology to the battle.

“If nanotechnology can be employed to control pests, it will greatly reduce the use of pesticides in the environment,” said Jeff Whitworth, a field crop entomologist with K-State Research and Extension. “And if researchers can find the right carriers for these nano-insecticides — products that may be considered organic waste — that may also reduce the amount of organic waste.”

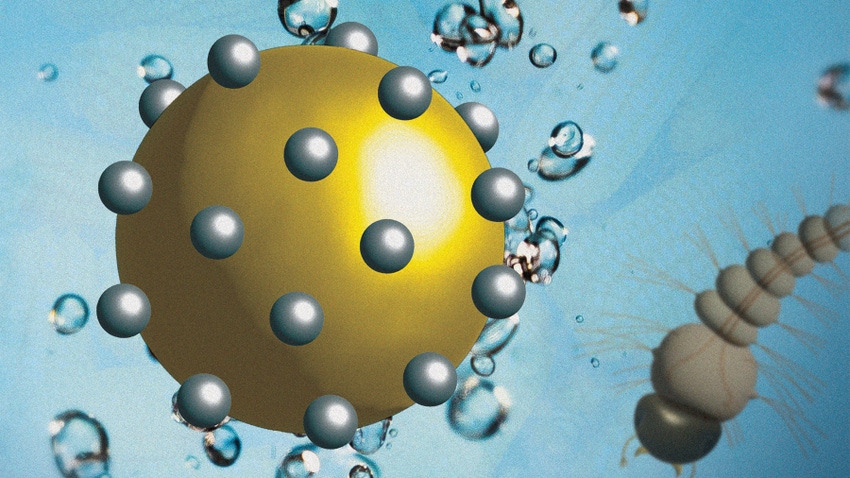

MOSQUITO LARVAE: K-State researchers are looking at ways to use nanomaterials to take a bite out of mosquitos at the larvae stage—getting them before they can get you. (frank600/Getty images)

Researchers at K-State, with four-year funding by the USDA, have made a breakthrough using nanomaterials attached to an antimicrobial that can kill mosquito larvae while using fewer insecticides in the process. The team reported this in the September issue of the American Chemical Society Omega Journal. According to K-State Research and Extension News Service, this is the first step in the larger goal of the university — to develop nanomaterials that may be viable tools against Hessian fly, corn rootworm, grasshoppers, termites and more.

The nitty gritty

What’s a nano? Well, according to KSRE News Service, a nanometer is one-billionth of a meter — a measurement so small it cannot be detected by electron microscopes. They compare it to a sheet of standard copy paper, which is 100,000 nanometers thick. The period at the end of this sentence is 1 million nanometers.

The K-State-USDA project takes silver, a known antimicrobial, and combines it with a corn protein, zein (pronounced zee-inn) to create a nanomaterial. The corn protein zein is a waste product that’s been used in biodegradable plastics, fibers, adhesive coatings and more.

As the mosquito larvae start to filter food from the water where they’ve hatched, they ingest this nanomaterial, and the silver gets into their midgut, killing the microbes that they need to survive, according to the researchers.

K-State nanoentomologist Amie Norton explains that the concentration of the pesticide in this nanomaterial from the K-State-USDA team is by far less than what would traditionally be used to combat mosquito populations. The K-State nanomaterial uses just 1 part per million of pesticide — similar to 1 drop of water in a 10-gallon fish tank.

A normal concentration of pesticides? A range from 10 to 32 parts per million, she says.

“The advantage of nanotechnology is that you have a larger surface area to work with, and nanomaterials have more bioavailability of active ingredients due to their size,” Norton says. “The increased loading of pesticides onto the surface of nanomaterials and their ability to increase the bioavailability of ingredients to targeted pests results in the use of less active ingredients [pesticides], which leads to lower costs for those using these products.”

Future applications

The goal is to find more ways to recycle agriculture waste by converting it to something useful, Whitworth said, and nanoparticles are the next step in scientific advancement.

While we typically don’t use silver today to control mosquitoes, future applications of this process could use a more common pesticide, spinosad, combined with a growth regulator like methoprene. That way, what doesn’t kill the mosquitoes will keep them from growing into adults, Norton adds.

To learn more, watch an interview with Whitworth and Norton online or below:

Source: Kansas State Research and Extension News Service contributed to this article.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like