October 27, 2017

Long before GPS was part of our acronym vocabulary, my early agriculture career started in eastern Iowa and northern Illinois. On one of those scorching hot July days, as you were driving through the area, every so often the road would be higher than the fields and you could visually capture a birds-eye view of the fields below. You could see parts of the fields, where the corn was rolled up tight as the plants went in to “protection” mode – while other parts of the field look perfectly normal. Images like that help make me an advocate that managing parts of the fields differently would make agronomic and economic sense.

Now those “pictures” can be captured in detail with a drone, a plane, or a satellite and further documented with your yield file. Since 80% of the US corn and soybean crop is rain-fed, we can’t solve the problem of running low on moisture in those drought-prone parts of fields. But we can manage those areas by changing the seeding rate – spreading the plants out a few inches can provide more room for the root mass needed to maximize yield and economic returns per acre.

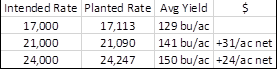

Premier Crop’s new Enhanced Learning Blocks allow users to use the equipment they have already invested in to do randomized and replicated trials. In this dryland Kansas field in 2016, two trials with 3 different planting rates and 5 replications each were conducted. In best area of the field, yields climbed as population climbed. We don’t know how high we should have gone but know that in the A zone (green), 24,000 returned $24 per acre more vs 21,000, including the additional seed investment.

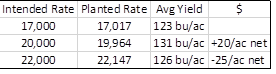

But the results in the B zone (yellow) were much different.

Consider what these results suggest about farming by the best average rate. If the grower plants 20,000 – the best rate for the B zone on the entire field – the grower loses at least $25 per acre on the best half of the field. Obviously, planting 24,000 on the entire field would be even worse economically. Picking 22,000 as the best “average” rate – mid way between 20,000 and 24,000 – would result in losing $18/acre on the A zone and $25/acre on the B zone.

If you think this might be worse case, consider that as you move east in the Corn Belt, both seeding rates and yields are higher. The higher the investment (higher seed costs) and the more return (higher yields) equates to even larger benefits to getting the rate correct. The story with nutrients is the same; the ideal rate changes within the field and economic reward or penalty is dramatic. Remember the example of having one foot in ice water and the other in hot water and the suggestion of being just right on average? Farming by averages is costing you profits! We can do better than choosing the best average rate.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like