Nitrogen. It’s on the collective agricultural brain these days, as Illinois presses toward reaching its nutrient loss reduction goals: cutting the state’s phosphorus load by 25% and its nitrate load by 15%, all before 2025.

In the southeastern part of Illinois, farmers and fertility experts are taking a hard look at what’s really going on — and what’s really running out of tile lines.

“Every single thing we do to increase yield is a nitrogen management tool. We’re applying for a certain yield goal, and the nitrogen we leave out there can turn into an environmental issue,” says Mike Wilson, specialty products marketing coordinator at Wabash Valley FS.

WASTE NOT: “What we’re learning is, we need to do a better job of applying nitrogen as the crop needs it,” says Mike Wilson, Wabash Valley FS. “We need to do everything we can to increase our nitrogen use efficiency. We’ve already spent the money on it — why waste it?”

Wilson headed up a nine-county project this year to measure tile drainage throughout the 2016 growing season. With help from Farm Bureau in each of those counties, the project received a grant from the Illinois Farm Bureau, which handed out $100,000 in nutrient reduction grants statewide this year. Wilson worked with Wabash Valley College to hire interns, and they monitored tile outlets in four or five fields in each of the nine counties throughout the growing season.

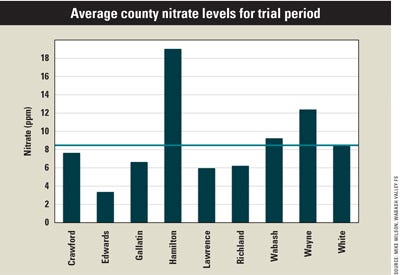

The counties in the study included Crawford, Richland, Lawrence, Wayne, Edwards, Wabash, Hamilton, White and Gallatin.

With help from the Illinois Fertilizer and Chemical Association, they also conducted an N watch study on one cornfield in each county. They monitored the amount of nitrogen in the soil and the amount leaving via tile drains, and did tissue tests to measure nitrogen utilization in plants. Plus, they administered a soil test to determine pH, sulfur, potassium, phosphorus and other nutrients.

The result of all the data?

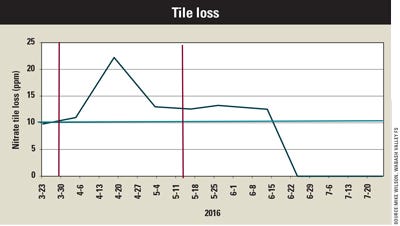

SPIKE: The April 20 spike in nitrate loss correlates with a rainy period that began the first week in April following UAN preplant application, says Mike Wilson, Wabash Valley FS.

“We do lose nitrogen after an application through the tile drains. Is it having an environmental impact? Not as much as we thought — we stayed below 10 parts per million throughout the study,” Wilson explains.

The plot thickened postharvest, when they found more nitrate left in the field than expected.

“We just didn’t use it. Was that because we applied too much? Because yields were down and the crop didn’t use it up?” Wilson asks, adding that they’re talking to each grower and showing him or her what happened.

“We need to change practices to make nitrogen use more efficient,” he adds.

Stable?

The study also revealed the effectiveness of stabilizers. Wilson says his 10-county Wabash Valley FS territory has a high rate of N-Serve use, around 60% to 75% adoption. But within the study, the farmers only put stabilizer in 40% of the nitrogen that was applied. “That floored me,” Wilson says. “We found that where we used it, it reduced the amount of nitrogen lost after a rain event.”

HIGHS? Mike Wilson with Wabash Valley FS explains that Hamilton County had fields boasting fall manure application, followed by sidedress. “Those fields don’t need any N; we figured that out!” Wilson says. “Some of those fields were still carrying 300 pounds of plant-available nitrogen — enough for the 2017 corn crop.”

Throughout the fields that were monitored, nitrogen application practices varied greatly. Some fields were in soybeans, so they could measure the amount generated and lost through beans. Some fields had preplant ammonia with N-Serve. Other fields were manure-applied the fall before (see Hamilton County data in the second chart) and sidedressed later. Still others had 28% applied preplant, followed by a topdressed urea ammonium sulfate. Others were sidedressed with ammonia followed by a second application of urea and ammonium sulfate.

“Applications were all over the board,” Wilson says. “The only constant was that we still had nitrogen left at the end of the year, and we didn’t expect it at that level.”

One farm that had been in continuous corn for 18 years (rare in that area) had preplant solution applied followed by 120 pounds per acre of actual N, followed by 120 pounds of urea and 50 pounds of ammonium sulfate. The field averaged 201 bushels per acre and had 1.1 pounds of nitrogen per bushel of corn use efficiency.

“When we took the last sample out of the field, it was still carrying over 70 pounds of plant-available nitrogen,” Wilson says, attributing the crop’s early death to corn rust. “It still had yield potential.”

A dry fall means tile lines aren’t running as frequently, but Wilson says when they do, they’re still getting 15 to 20 ppm following a rain, which means they’re still losing nitrogen.

“What we’re learning is, we need to do a better job of applying nitrogen as the crop needs it,” Wilson concludes. “We need to do everything we can to increase our nitrogen use efficiency. We’ve already spent the money on it — why waste it?”

Geographic spread

Wilson has a major takeaway from the study, aside from their N-use abilities: Geography matters.

“Things change from one side of Wabash County to the other, let alone from Shawneetown to Hidalgo. Then you look a hundred miles west or a hundred miles north? It’s a world of difference,” he says.

“Farmers are willing to do the right thing, but they need good advice by their geography. What we’re doing here won’t work where you’re at. And if we’re going to follow the guidelines of the Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy, we need good certified crop advisers giving farmers good information.”

In the end, on-farm research is invaluable, Wilson says. “Farmers have to do their own on-farm research, and there are consultants who can help with that.”

Glass half full?

How about that volunteer corn crop? Wilson tells of a field in their study that’s been in continuous corn for 18 years, and the field had 3% organic matter and a 25 cation-exchange capacity. The farmer harvested it the third week in August — and his volunteer corn tasseled.

“It was so green and had so much nitrogen, we think it helped tie up that nitrogen,” Wilson says. “I’m a glass-half-full kind of guy, so that’s a pretty cheap cover crop!”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like