From the beginning of time, some agriculturists have marveled (if they thought about it at all) at the idea prairies and forests produced prodigiously without added fertility.

At last we're beginning to understand how such a thing can be accomplished, better yet mimicked.

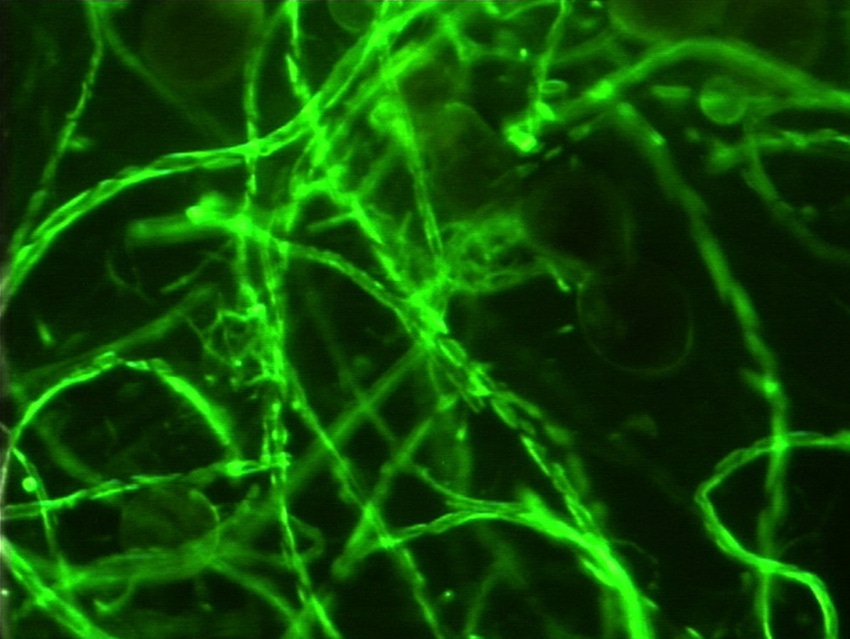

A big part of the seemingly supernatural is done via a massive underground network of fungal superhighway that links many species of plants to microorganisms and transfers and shares huge amounts of vital plant compounds such as nitrogen, phosphorus, manganese, sulfur -- all the major and minor plant nutrients -- as well as plant-produced carbohydrates.

The star of this show is an organism called arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Together with its army of associated microbes, it can mine every major nutrient from the parent material of all soils, store huge amounts of carbon in the soil, hold and share water, moderate acidity and alkalinity, and build soil structure like nothing else.

Yet nearly every major agricultural practice of the past 10,000 years has torn it apart, to the detriment of mankind. As we have destroyed this life-giving fungi with tillage and set-stocked overgrazing and further with high rates of fertilizer and with long fallow periods, we have slit our own throats and made ourselves dependent on truly mined minerals, which we must draw out of nature with massive expenditures of human energy and millennia-old fossil fuels.

One example of this fungi's magic is a compound it manufactures called glomalin, only discovered in 1996 by ARS soil scientist Sara Wright. It is a carbohydrate-based "soil glue" that contains 30-40% carbon. Glomalin is the substance that creates clumps of soil granules called aggregates. These are what add structure to healthy soil. They also keep other stored soil carbon from escaping.

Technically glomalin is considered a glycoprotein, which stores carbon in both its protein and carbohydrate (glucose or sugar) subunits. Because it stores so much carbon, glomalin is increasingly being included in studies of carbon storage and soil quality.

Further, scientists have found glomalin weighs from 2 to 24 times more than humic acid, which is the byproduct of decaying plants that once was thought to be the main contributor to soil carbon storage. Now scientists say humic acid contributes only about 8% of soil carbon.

As I alluded, glomalin is just one of the benefits of this amazing creature we're calling AMF. The more we can harness its amazing qualities to help farm and ranch, the less money we can potentially spend and the more profit we should be able to make.

We're focusing on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), what it does, and how to have more of it in the upcoming June issue of Beef Producer. So keep an eye on your mailbox. We'll also publish all that material and more here on the website.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like