How does a kid from Harlem in New York City end up as an assistant commissioner in the Minnesota Department of Agriculture?

Let’s just say it took a gentle nudge from a loving mother.

Patrice Bailey was in his senior year of high school, and he and his mother were having a conversation about what he was going to do after he graduated. “I said that I wanted to go to law school. She said, ‘There are too many lawyers. Why don’t you do something where you can actually feed yourself anywhere in the world that you may find yourself?’”

She suggested her son take an agriculture path in college, to which he recalls responding, “Mom, look, we live in Harlem. There is no knee-high in July.”

Bailey was aware of New York agriculture in the form of apples and dairy, but he admits he didn’t know what that looked like other than the stereotypes. “You know, the bib overalls, a John Deere hat and some dusty boots,” he says.

His journey in agriculture to the present started his freshman year at Prairie View A&M University, a public, historically Black land-grant university (HBCU), where he studied agriculture education.

Leaving the concrete jungle of Harlem, where the closest thing to agriculture was Central Park, to land in Prairie View, Texas, was in some ways a culture shock. Prairie View’s population was right around 8,000, compared to Harlem’s 197,000, but at the college, he saw familiar faces — not so much that he personally knew the people, but he saw what he could become.

With Prairie View A&M being an HBCU, “you see a lot of people that look like you,” Bailey says. “It was an embracing shock, because now I’m like, ‘That person is a VP. I can be a VP; I can be this.’ So, the ability to see yourself in different spaces in real time, it was really welcoming to be able to see yourself reflected on campus every day.”

Ag in big food

Though surrounded by many who looked like his own reflection, Bailey still harbored negative views of agriculture. A trip to the Worldwide Food Expo in Chicago opened his eyes to the opportunities, where he saw the connection large food companies had to ag. A chance encounter there also helped paint a clearer picture of agriculture.

A conversation Bailey had with Charlie Walsh, who was staffing the Pepperidge Farms exhibit, further changed his ag view. “That was the same guy that I saw on the commercials when I was a kid,” he recalls. “It was that conversation that changed my worldview as to how I looked at agriculture from the lens of someone from a city.”

Bailey’s ag mindset continued to blossom through two college internships with the U.S. Forest Service in Idaho.

It wasn’t until 2005, when he joined the University of Minnesota’s College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences, that he was introduced to Minnesota agriculture. At CFANS, he supported recruitment in agriculture education.

Pride in emerging farmers

Fourteen years later, when Bailey joined the MDA, he became more immersed in Gopher State agriculture, an industry largely devoid of people who resemble himself.

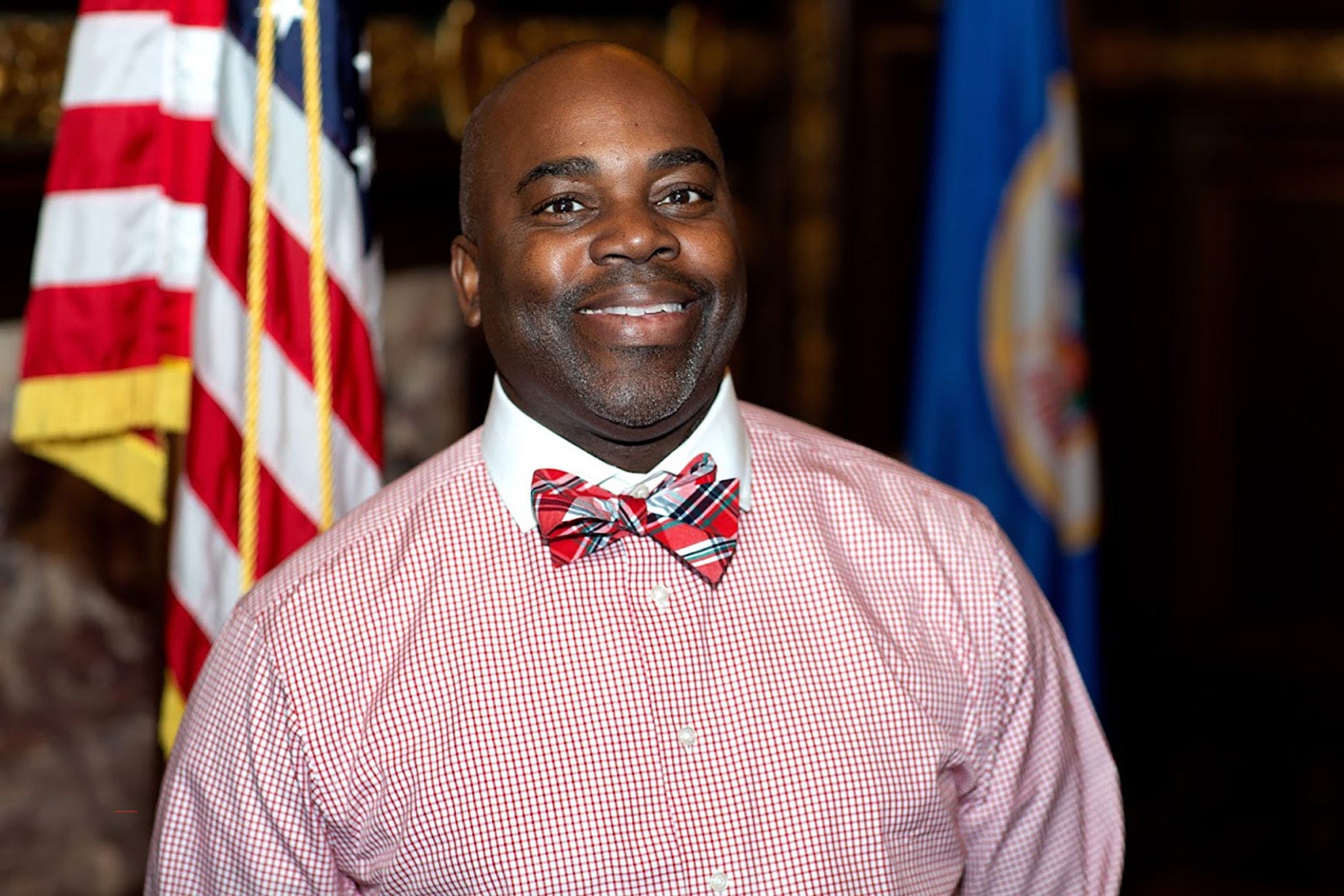

BREAKING BARRIERS: As an assistant commissioner in the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, Patrice Bailey aims to create opportunities for underrepresented populations looking to get into farming in Minnesota. (Minnesota Department of Agriculture)

While he oversees outreach, agriculture marketing and development, dairy and meat inspection, and food and feed safety for the MDA, he feels most pride in the development of the Emerging Farmers Working Group and the Emerging Farmers Office within the department.

“We established the working group to break down some of these barriers, not just in the African-American neighborhoods, but also in native neighborhoods,” Bailey says. When asked to dream, if money were no object, “I said I would ask for an office with a dedicated person. I would also ask for translation services to be able to communicate with more people throughout the state.”

The fruition of the Emerging Farmers Office culminated with the hiring of Lillian Otieno last fall to serve as the office’s first director. Bailey says Minnesota is the first in the union to have such an office, though other states are looking to replicate the Minnesota model.

He credits those in the Legislature and communities who worked toward the creation of this resource for prospective agrarians, regardless of their ethnicity, color of skin or background. “No one does anything in silos,” he says, figuratively speaking, “and that’s a conversation of what I would tell different emerging farmers … not to silo yourself, because you need each other in order to be successful in this state, especially when it comes to agriculture.”

Whether it was growing up in Harlem, attending college at Prairie View A&M or graduate school at Iowa State University, or working at Wartburg College, the University of Minnesota or the MDA, Bailey has lived his life outside of silos, knocking down barriers for those in previously underserved populations.

Bailey believes a lot has been achieved in the four years since the EFWG started, “making a difference for all Minnesotans. … It’s a beautiful thing to be able to see it, but it also is a lot of hard work in order to pull it off. And it’s a lot of standing firm on your convictions because it’s the right thing to do, not only for yourself, but also for those who are soon to be contributors to agriculture who may not know that’s what they want to do, but at least the barriers to entry are lessened because of people before them who have advocated for things to change.”

What’s an HBCU?

The Morrill Act of 1862 established the land-grant university system in the United States. Passed and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln in the middle of the Civil War, it granted federally controlled land to states. States could then use that land to establish land-grant colleges with the mission of teaching practical agriculture, science, military science and engineering skills. The law democratized higher education.

In 1890, a second Morrill Act was passed establishing more land-grant colleges to provide opportunities for people of color. Between 1861 and 1900, more than 90 institutions of higher learning were established. The Higher Education Act of 1965 defined any historically Black college or university established prior to 1964 with the principal mission of educating Black Americans as a historically Black college or university, or HBCU.

Prairie View A&M University is one such HBCU. It’s the second-oldest public institution of higher education in Texas and originated in the Texas Constitution of 1876. Today, graduates from its College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources see a 90% job placement rate, according to the university’s data.

The National Institute of Food and Agriculture offers a College Partners Directory, so you can find universities near you with agricultural programs.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like