July 5, 2016

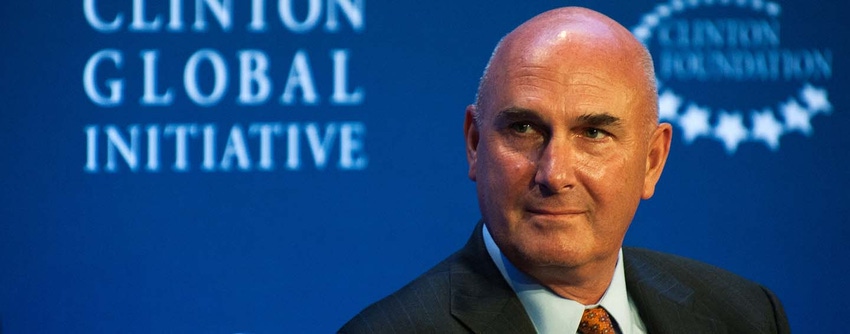

Monsanto Co. Chief Executive Officer Hugh Grant is at risk of becoming the corporate equivalent of the star-crossed romantic usually played by his floppy-haired actor namesake.

The boss of the world’s biggest seed maker, which rejected a $62 billion takeover offer from German rival Bayer AG last month, has made the case for industry consolidation more often -- and more loudly -- than many others. Thus far, however, he has failed to find a partner.

On Wednesday, Grant returned to familiar ground when he told shareholders he was discussing a number of potential deals.

“Monsanto remains the partner of choice in this industry and I assure you that we will continue to actively explore these opportunities,”’ he said, as the company posted lower-than-estimated profit and sales for its fiscal third quarter.

It’s a belief that’s informed much of his decision making for the past two years.

In early 2014, Monsanto -- then valued at about $64 billion -- approached Swiss pesticide maker Syngenta AG about a tax inversion deal, which would have allowed Monsanto to move its tax base to Switzerland. Combining the two companies would have created the largest player in the world for both seeds and crop chemicals. But Syngenta demurred and the talks fizzled out, people familiar with the matter said at the time.

Less than a year later, Grant tried again. Again, Syngenta said no. This time Grant dug in for the fight.

Inevitable Consolidation

The 58-year-old Scot, tall and soft-spoken, spent months criss-crossing the globe to lobby shareholders of both companies to back a deal. Consolidation between groups that developed crops and those that produced the chemicals to treat them was, he said, inevitable.

Mike Mack, Grant’s counterpart at Syngenta, refused to engage.

By July, Grant’s patience was wearing thin. In an interview with Bloomberg, he said Syngenta’s unwillingness to talk was sparking a “crescendo of growing impatience on both sides of the Atlantic.”

“There are two outcomes in this: ‘No’ means ‘no,’ and ‘no’ means ‘yes,”’ Grant said. “I think it’s ‘no’ with an embedded ‘yes.”’

He was right -- sort of. Syngenta, then under the interim leadership of John Ramsey, did say yes, but to China National Chemical Corp., known as ChemChina, agreeing in February to sell itself to the state-backed entity for about $43 billion.

Small Acquisitions

In the months that followed, Grant backed away from the argument that large-scale M&A was necessary. He said earlier this year that Monsanto would instead use licensing, partnerships and small acquisitions to reach its vision of a fully integrated solution for farms.

Then Bayer crashed the party.

In May, the German company went public with its bid for Monsanto, deploying many of the arguments Monsanto had itself used for industry consolidation. The move put Grant in a tough spot.

He had to balance his own statements about the benefits of M&A with a desire to keep Bayer from acquiring Monsanto on the cheap -- the company’s value had fallen by almost a third since its first approach to Syngenta in 2014.

Monsanto and Grant hedged. The company responded to Bayer’s offer by saying it was too low, but that it recognized the benefits of consolidation and was open to further talks.

Since then, there have been talks between the two companies but nothing has been agreed. Most of the deliberations at the moment are just talking about talking, rather than actually discussing a deal, one person familiar with the dialogue said.

Grant is open to a deal at the right price, according to people familiar with the matter, but also holds out hope that Syngenta’s deal with ChemChina may fall apart, opening the door for Monsanto to make a third run at buying the company.

ChemChina, for its part, is confident it can get the deal done, one person familiar with that process said. Despite recent volatility sparked by British voters’ decision to leave the European Union, Brexit has had little impact on negotiations, and financing for the purchase is still in place, the person said.

Representatives for Bayer and Monsanto declined to comment.

Asset Swaps

Monsanto has also explored possible asset swap deals with partners such as BASF SE, Bayer’s German rival, people familiar with the matter said in March. The U.S. company brought up that possibility in its earning release Wednesday, acknowledging it has been in discussions about “alternative strategic options” over the last several weeks with Bayer, as well as with other parties.

Meanwhile, takeover talks with Bayer are at a standstill. The German suitor is reluctant to increase its offer without first taking a proper look at Monsanto’s finances, while Monsanto wants the reverse: A bump in price that’s contingent on due diligence, but without opening its books first, the people with knowledge of the process said.

Despite the gridlock on price, both parties in the latest round of talks have been playing nice: There have been no negative attacks in public from either side, and even privately Grant has been careful not to say anything that might stand in the way of a deal, the people said.

Whether with Bayer or someone else, Monsanto now seems destined to find a deal. For Grant, that could mean finally finding a partner at the dealmaking dance he started.

--With assistance from Jeffrey McCracken, Aaron Kirchfeld, Lydia Mulvany and Johannes Koch.

To contact the reporter on this story: Ed Hammond in New York at [email protected]

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Elizabeth Fournier at [email protected]

Elizabeth Wollman

© 2016 Bloomberg L.P

You May Also Like