Commodity options cost money, sometimes too much for farmers who’d like to incorporate puts and calls into their marketing plans.

There are a lot of ways to lower this expense. Options that expire sooner than others are usually cheaper. Contracts that are “out of the money” with less chance of paying off also cost less. Using a spread is another strategy, selling one option to pay for another.

But with options, as in life, you get what you pay for. If an option costs less, there’s a reason.

This logic holds true with one of the basic ingredients in the pricing of options. The amount of uncertainty about the future direction of prices plays a big role in determining how much they cost.

Consider the seller of an option. A call option conveys the right to buy futures for a preset strike price, so those who write them are at risk if futures rise. Puts grant the buyer the right to sell futures, so the writers can lose money if the market tumbles.

Options are sometimes considered price insurance, and their costs reflect it. The companies that sell car insurance know the odds of you crashing your car, and can sell you coverage that will make them a profit over time. They also know a teenager is more likely to crash, and they charge more for those policies.

But commodity prices are not as predictable as car crashes. And emotional trading can cause perceptions of risk to rise and fall swiftly, taking options costs along for the ride. In the calculation of option premiums, this is known as implied volatility. It’s the market’s judgment of how much prices might change over the life of an option.

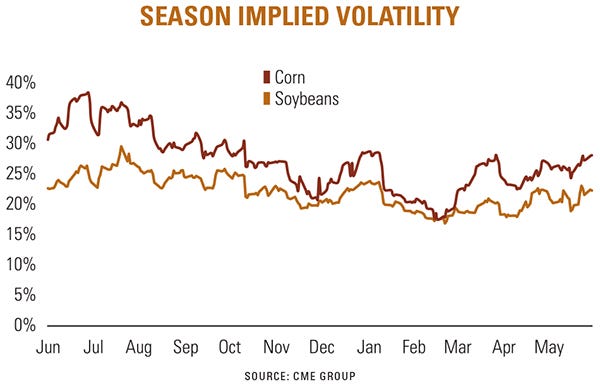

Volatility has a seasonal component the same way futures often trade according to the calendar. But options and futures volatility can take different twists and turns.

Uncertainty for both futures and options is greatest during the growing season, when crops are most at risk. So corn and soybean futures tend to peak during the summer, typically around the Fourth of July.

That’s when corn options volatility also spikes. Uncertainty for soybeans comes a little later, and options volatility peaks in August, when that crop is made.

Corn and soybean futures typically make a low in late September or early October, and then rally a bit into the end of October or early November. That rally in fall 2016 provided opportunities for growers to get more price protection. If they turned to the options market, volatility worked in their favor. It tends to keep easing all the way into expiration of December options in late November. Most of the uncertainty over the size of the crops is history by then.

Nonetheless, from Thanksgiving to early January, volatility tends to rise. Traders heading to the exits for a year-end vacation tend to square positions to minimize risk. That can mean buying puts to protect long futures, or buying calls to offset shorts. Those cashing out of futures can also buy options to keep a leg in the market, just in case, say, of bad weather in South America.

More demand tends to raise the cost of the options, increasing the implied volatility.

Positioning can also be in the run-up to USDA’s January crop reports, in the second week of the new year.

After that, volatility normally eases again until late February, before rising in March as uncertainty over acreage plans mounts. The overall trend is then higher into summer, with planting and growing season weather kicking off the cycle again.

- Decision Time: Risk Management is independently produced by Farm Futures and brought to you through the support of Case IH.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like