Droughts are one of nature’s nomads – always coming and going, and never staying too long in one place.

Last winter, drought’s footprint in the U.S. covered as much as two-thirds of the country by the end of January before seeing modest reductions throughout the spring and summer. Now, the latest data suggests that drought may be on its heels again as it continues to diminish.

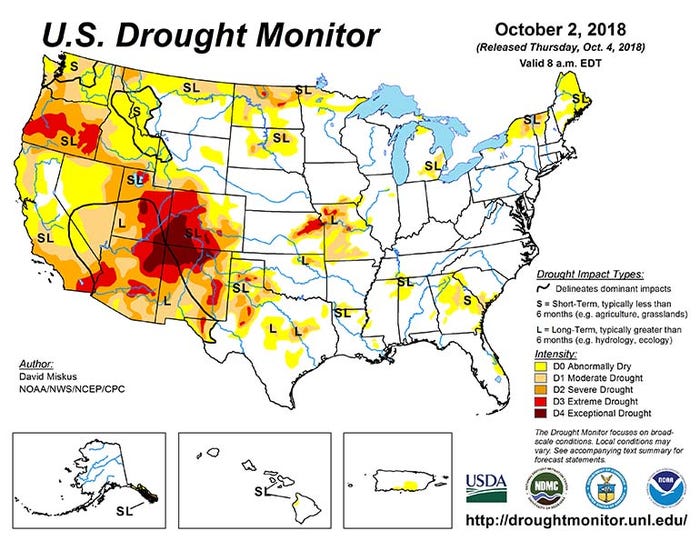

The latest updates from the U.S. Drought Monitor, out Oct. 4, have 47.4% of the country experiencing some level of drought, which marks seven straight weeks of decline and the lowest such percentage overall since mid-June.

Of that, only 7.3% of the country is in the two most severe categories of D3 (extreme) and D4 (exceptional). Farmland in these categories can suffer not only shorter term agricultural challenges, but also longer term hydrological and ecological impacts if these conditions persist.

Currently, the bulk of damaging drought in the U.S. exists west of the Rocky Mountains, but some problem areas are still hanging on in parts of the Midwest and Plains. Currently, 17% of the Midwest is experiencing some level of drought, versus 47.6% a year ago. Missouri has inherited much of the remaining adverse conditions, with a few spots of drought also creeping into parts of eastern Michigan and northern Minnesota.

In the Plains, western Colorado is the primary problem area, although eastern Kansas and the Dakotas are also experiencing some adverse conditions. As a whole, the region has a slightly larger drought footprint (44.9%) now versus one year ago (40.1%).

Moving forward, is drought’s footprint likely to diminish more, or will conditions reverse again and create new problem areas? David Miskus, meteorologist with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, notes that the extended range outlook that covers October 9-13 favors above-normal precipitation for much of the Continental United States during this time.

“The highest odds [are] across the north-central Rockies, Great Plains, and middle to upper Mississippi Valley,” he notes in his latest summary on the U.S. Drought Monitor.

And NOAA’s three-month outlook from November to January predicts below-average precipitation for much of the Pacific Northwest, while wetter-than-conditions are more likely across the southern third of the U.S. If El Niño conditions develop later this fall or winter, that will help reinforce these expected trends.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like