Net farm income is projected to be $88 billion this year, 4.8% higher than 2018. In fact, it’s in the top 30% all time in years net farm income has been measured.

“But when I talk to our farmers and ranchers, people aren’t saying things are better,” says John Newton, chief economist at American Farm Bureau Federation.

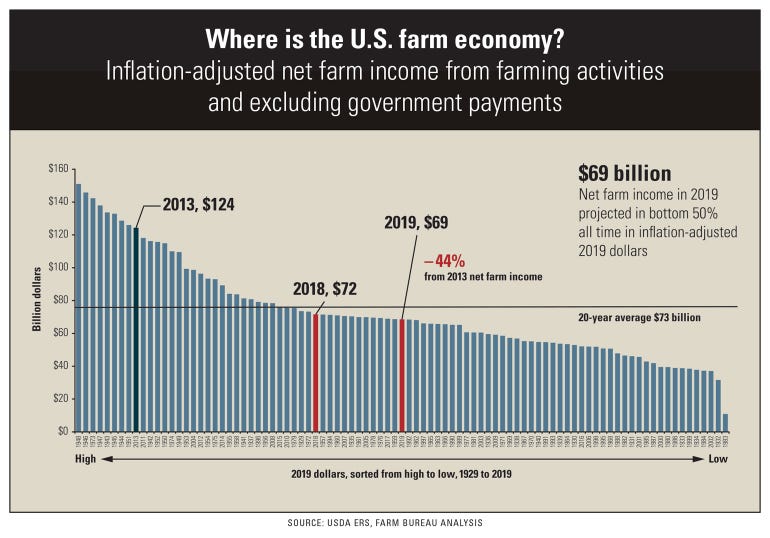

Take out $19 billion of federal government support in the form of trade assistance and other support and net farm income is adjusted to $69 billion, which is in the bottom 50% all time in net farm related income.

Farmers on the front lines know it’s been a tough year, especially in the wake of late plantings and now late harvesting in many places. But Newton, speaking at a Farm Foundation forum on ag economics, says a plethora of issues have contributed to net farm income declines.

Global ag output increased significantly between 2006 and 2012 — by 40% in China, by 35% in the rest of Asia, by 36% in Brazil and by 17% in the U.S. Toward the latter years of that increased output, though, economies in many countries started to slow down, resulting in overproduction and decreasing demand.

Trade disputes have made the situation here in the U.S. worse.

“The downturn in the farm economy has been exacerbated by the slowdown in ag exports,” he says.

In the 2018-19 crop year, the U.S. exported 546 million bushels less soybeans to China than in years past, according to Newton. China used to purchase one-third of every acre of soybean produced in the U.S. Now they purchase 11% of each acre, he says. Exports of tobacco, grain sorghum and cotton have also gone down.

Countries such as Argentina, Italy, Spain and even Mexico have increased purchases of soybeans. Argentina bought 65 million bushels of soybeans last year, he says, a big increase over the previous year, but that was due to a shortage of soybeans from a bad growing season.

Even with all these countries stepping up, Newton says it still can’t replace China’s role in soybean exports.

Cash rents, he says, have declined in many parts of the country, including by 11% to 14% in Iowa. Farm equity ratios have declined for seven straight years.

Farm debt is at $416 billion with delinquency rates at their highest level since 2012. More and more farmers, he says, are behind in their loan payments, and many farmers have extended their loans out.

Chapter 12 farm bankruptcies are also up. In the Mid-Atlantic, they are 15% higher than last year.

Is there any light at the end of the tunnel? Newton says he’s hopeful considering crop insurance payments have yet to go out and more trade aid might be in the offing. The first Market Facilitation Program payments went out in August. The second and third payments will go out as market conditions and trade opportunities dictate. The second portion, if necessary, will be made next month, while the third portion will be made in early January.

Keith Coble, ag economics professor at Mississippi State University, talked about public sector funding for ag research. He says China surpassed the U.S. in public ag research dollars in 2009, and that gap is getting wider.

Coble also touched on crop insurance and the fact that the program’s aggregate loss ratio — how much it takes in versus how much it pays out — is in the positive, but the effects of climate change must be considered in future Risk Management Agency programs and policies, he says.

"We are outpacing climate change; that doesn't mean we're going to continue outpacing climate change," he says.

With farm economics the way they are and the continued development of technology, he says the largest farms will be in the best position to use data and become more efficient.

Midsize farms, especially ones that are not efficient, will continue to exit the business, while smaller farms will also increase because they can better target specific local markets.

The new normal

Seth Meyer, associate director and research professor of the University of Missouri’s Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute, thinks this might be the new normal of ag economics.

He says the ag economy has just come off the longest period of above-average farm income since the end of World War II. Current farm income is much in line with historic trends, he says.

On the supply and demand side, Meyer doesn’t see another boom anytime soon since worldwide ag production has increased, and emerging economies aren’t growing as fast as they were in the 2000s and early 2010s.

So, are there any positives in farm country? Coble says the low commodity prices are making it more affordable to feed animals right now, so that’s a positive for farmers who are raising beef and dairy.

You can’t predict when the next demand or supply shock will be, Newton says, but farmers he’s talked to say they want to know what the trade rules are so when opportunities arise they will be ready to take advantage.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like