In 2007, the concept of a “black swan event” burst on the scene with the release of Nassim Taleb’s book by the same name. The New York Times bestseller served up the fresh concept, at the time, that extremely unpredictable events felt much more predictable in hindsight. But in reality, black swan events just show how poorly we can be at predicting the future, and how unpredictable events can have a massive impact on our daily lives.

Sound familiar?

“It seems as though we’ve had a once-in-a-lifetime event in each of the past five years,” says Jacqueline Holland, grain market analyst at Farm Futures. That includes a trade war with China, a global pandemic, unprecedented supply chain holdups, Russia’s war on Ukraine and, more recently, war in the Middle East.

Each of these black swans had an unpredictable, yet mainly positive, impact on grain markets; yet, they are one-offs. To ensure the best chance for profits in ’24, it’s important to keep your eye on more traditional fundamentals and assess how they impact global production, as well as supply and demand.

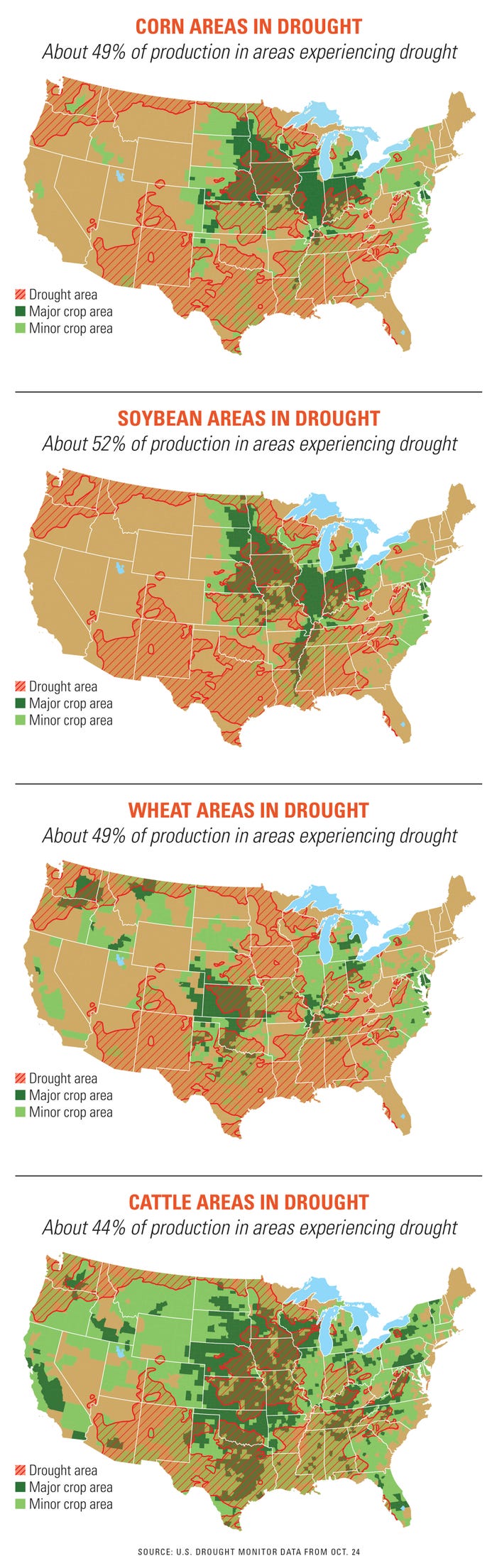

Drought, for example, is having an impact in both North and South America now.

“Water management isn’t talked about enough,” Holland says. “So many places need rain and not just for row crop production. We also need water to revive pastures and re-expand the cattle herd.”

As of mid-October, 50% of corn production and 53% of soybean production in the U.S. was in an area experiencing drought. On the livestock side, 44% of cattle inventory and 59% of hog inventory were also in an area experiencing drought.

“We’ve gotten some rain this fall, but I do not want to go into a freeze-up in a drought situation, then have to rely on every drop of rain next spring,” says Iowa farmer Chris Edgington. “We need some water in the tank to be optimistic going forward.”

The grain market also has Edgington keeping his

eye on weather in South America — which could boost soybean prices if dryness there continues — and U.S. corn exports.

“Corn has three places to go: ethanol, livestock and exports, which haven’t been good the last year and a half,” he says. “So, we need to build that back. Some of it may come from corn being priced at $5 per bushel or less, making it more attractive for overseas buyers. But continued havoc around the world makes this a safe haven for investors, so the value of the dollar is up. That’s good for some things, but it’s not good for exports.”

Volatile input prices make locking in profits even harder in the current environment, adds Illinois farmer and market analyst Matt Bennett. “Hopefully, farmers have locked in ’24 fertilizer prices, because they have already started to creep up,” he says.

Bennett says one mistake to avoid is a repeat of ’23 when some farmers locked in high fall fertilizer prices, yet did not lock in a forward sale to offset those higher input costs.

“That wasn’t a good move,” he says. “Any time we buy inputs but do not lock in a sale on our output, we’re setting ourselves up for potential failure.”

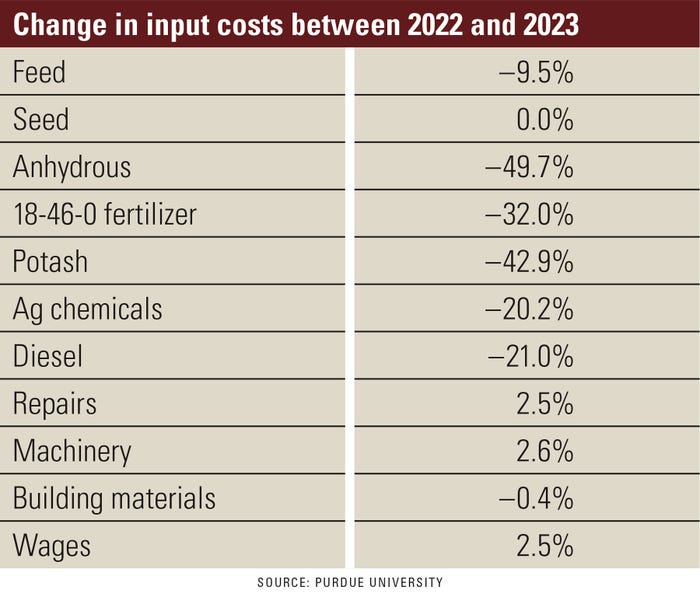

Holland is encouraged to see some input prices — particularly for several types of fertilizers — drop between August 2022 and August 2023. Anhydrous prices were down nearly 50% during the period, and potash was down almost 43%.

“Input markets have seen some huge pendulum swings over the past couple of years,” she says. “Right now is a good opportunity for farmers who have come off some really strong, profitable years to put some of that cash to use for next year’s production. I’m worried that input prices will go up again sooner rather than later.”

Despite the large decreases in the last 12 months, fertilizer prices are still well above what they were in 2020, says Michael Langemeier, a Purdue economics professor in a summary of a recent university study.

“Over long periods of time, farm input prices are significantly correlated with general inflation,” he notes. “However, farm input prices are by no means perfectly correlated with general inflation. Each input has its own supply-and-demand fundamentals.”

Interest rate unease

High interest rates are also bound to create a ripple effect of problems throughout the industry, says David Widmar with Agricultural Economic Insights. “That’s a huge source of uncertainty,” he says. “Even if you aren’t borrowing money, it still affects you in a lot of ways.”

Edgington is also all too aware of this reality. “Interest rates are double what they were in 2022, and ag is a highly intensive industry when it comes to using bank money for either short or long periods of time, so that cost will play a role in next year’s bottom line,” he says.

Widmar quotes the oft-cited saying: “Chance favors the prepared mind.”

Each year, his company updates a list of the three biggest industry risks, and Widmar urges farmers to engage in a similar process for their own operation.

Sit down and work out three areas of improvement that you can focus on in the coming year. Prioritize each item and write a short summary of what you’re hoping to accomplish. Then, share the document with lenders and other trusted advisers.

This requires a bit of humility, Widmar admits.

“It’s challenging, but it’s important,” he says. “It might be scary sharing something like this with your lender, but it shows that you are proactive and will allow you to have more meaningful conversations.”

Widmar likens this exercise to basketball. There are good shots and bad shots, but you’re going to have to take one eventually.

“You can pass the ball all you like, but you have to take a shot to win the game,” he concludes.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like