Six trends you can’t afford to miss if you’re in agriculture

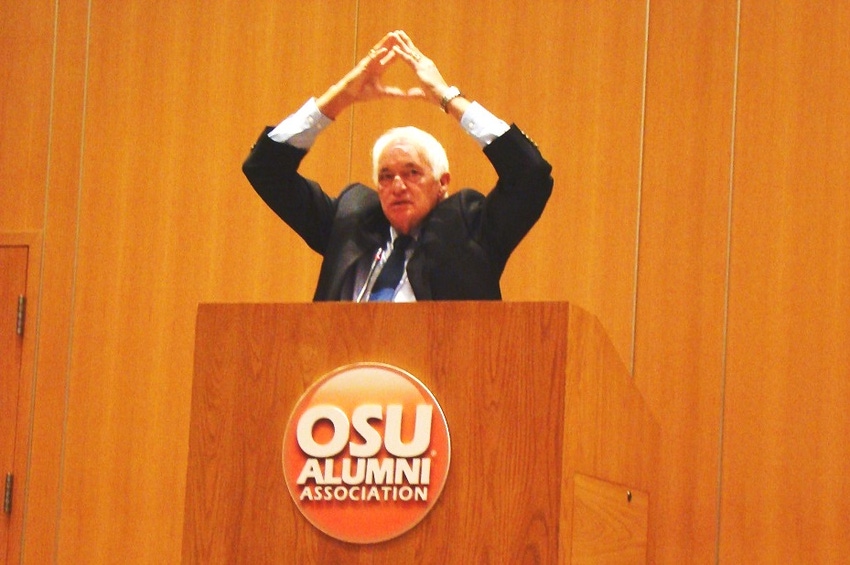

Lowell Catlett's presentation, a mix of distinctive detail and barbed quips, is designed to amuse and educate. He pokes fun at his own profession from the get-go.“Economists exist so meteorologists will have someone to laugh at,” he said, as he warmed up the Stillwater, Okla., audience for his discussion entitled “Six Trends You Can’t Afford to Miss.”

Lowell Catlett doesn’t dismiss the obstacles facing agriculture today. He chooses to look beyond them.

“There has never been a better time to be in agriculture,” he says. “There has never been a better time to live in rural America.”

The Regents Professor in Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business and Extension Economics and Dean of the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at New Mexico State University, spoke at the recent Oklahoma State University Rural Economic Outlook Conference, where the focus was on the many challenges facing agriculture — low commodity prices, increased production costs, and the uncertainty of ag lending, among others.

For the latest on southwest agriculture, please check out Southwest Farm Press Daily and receive the latest news right to your inbox.

Catlett also bills himself a “futurist,” one who explains, in terms that even a liberal arts major can grasp, how technology will, and is, changing our lives for the better. His presentation, a mix of distinctive detail and barbed quips, is designed to amuse and educate. He pokes fun at his own profession from the get-go.

“Economists exist so meteorologists will have someone to laugh at,” he said, as he warmed up the Stillwater, Okla., audience for his discussion entitled “Six Trends You Can’t Afford to Miss.”

The accuracy of economists’ predictions has been pegged at 47 percent, he says, but “You can flip a coin and beat that by 3 points.”

The irony that the analysis of economists’ accuracy was most likely developed by economists isn’t lost on Catlett.

Climate change, he says, has “been up and down, weird as hell, but the world has experienced the largest economic output ever recorded. Production of greenhouse gases is down over the last decade, production (manufacturing) is up, and pollution is declining.” China, he says, is depending on fewer coal-fired plants, and the world has added more trees in the last 25 years than it harvested.

AG HAS DONE ITS JOB

The first trend farmers and ranchers should be aware of, Catlett says, is world wealth. “In 1970, the United States became the first $1 trillion economy. But, the world couldn’t provide 2,450 calories a day to the world’s population. We could do it in the U.S. and Canada, but not the world. There were gloom-and-doom forecasts and estimates that the world population would top 12 billion by 2015. Instead, it’s just over 7 billion.”

In the 1970s, China, India, and Brazil accounted for half the world’s population, he says, but they “didn’t produce as much as the United Kingdom. China’s production was half as much as that of the U.S.”

In 2014, the world population stood at 7.2 billion, he says, and there was enough food to provide 2,900 calories for every person on the planet. Hunger still exists, he concedes, but not because too little food is available. “Agriculture has done its part — over the last 21 years, the fastest growing food segment in the U.S. has been diet products.”

As people begin to accumulate more wealth, Catlett says, a key goal is to improve diets, especially to add more protein. And once consumers begin to improve their diets, they are reluctant to change. “Once you go up, you don’t want to go back down. That’s important for agriculture.”

Consumers with money also look for specialty items, including “natural foods,” and things like craft beers. “In 1970,” he says, “there were no craft beers in the U.S. — now, we have 4,000. In fact, we’re seeing a hops shortage.”

IMPROVED GENETICS, MANAGEMENT

The demand for natural foods, such as free-range chickens and other organic and grass-fed foods, may be niche markets, he says, “But, considering the income effect, we will need to increase food production by 50 percent, and we won’t do that with pastoral agriculture.”

Good genetics and improved management will boost production by about 20 percent, Catlett says. Producing the rest of what a growing world will need will require “concentrated production agriculture, intensive animal operations — research shows these facilities have the least impact on the environment and the best feed efficiency. We will maintain pastoral agriculture. People will pay for natural agriculture products.”

They also will pay for experience, he says. He wonders what would have been the reaction of a Midwest corn farmer 40 years ago had someone wanted to come into his field and cut trails at odd angles in the middle of the plot.

“Corn mazes didn’t exist then — now you have to pay $5 to go through one. This is the best time ever in agriculture.”

Much of that is a result of the amount of money in the world, Catlett says. “In the U.S., the net worth of 120 million households is $87 trillion, the largest net worth ever on the planet. It provides them the opportunity to buy craft beers and free range chickens.” It also means a bigger demand for protein. “No one can meet twice the demand for meat production except the United States.”

FOLLOW THE MONEY

He says the second trend agriculture needs to consider is who owns all that money. “Two-thirds (of the $87 trillion) is held by Baby Boomers, and 1 in 20 of them has Alzheimer’s. Over the next 10 years, we will see the largest transition of money from one generation to the next in history. By then, it should be up to $150 trillion.”

But the money now in agriculture may not stay in farm and ranch holdings, Catlett says. “Only 20 percent of all businesses survive the second generation, and only 4 percent survive the third generation.” That’s not because of losing money, he notes. The generation that inherits wealth often looks to other occupations. “It ain’t my passion is a typical response to why the next generation moves to something else.”

The generation following Baby Boomers was the first to “grow up with money,” he says. “It’s also the smallest generation —making money the best birth control ever. The smallest generation is also the best-paid.”

MILLENNIALS GET BAD RAP

These Millennials shouldn’t be underestimated, Catlett says. “They get a bad rap. They are the first generation ever that has grown up and has never lived without mobile communication.

“Baby Boomers were the first me, me, me generation. We protested on college campuses, smoked dope and took drugs. We still do — but it’s now Metamucil and Prozac. We shaved our hair and went to work.”

Millennials know mobile communication from top to bottom, he says. “The biggest use of the Internet now is social media. Millennials are really good at it; they’ve changed society. What goes on in Vegas, or wherever, is now on Twitter within minutes. This is the most transparent society in history.”

Millennials offer a lot to society, he says. “Embrace them.”

The mobile communications age also brings the third trend —a seamless world. “Transparency is now second nature,” Catlett says. “We have fabulous technology.” The “tricorder,” a futuristic device used by Dr. McCoy on the old Star Trek TV series, is now reality in an instrument that can do blood work through a mobile app, he says. Yet another device can analyze a blemish and determine if it is cancerous or benign. “We’re seeing a phenomenal revolution in self-diagnosis.”

Another app allows a user to check a plant leaf for signs of stress. Yet another uses facial technology to determine a person’s mood—technology that an automobile company is using to choose specific music to match or change a driver’s mood.

“The first truck my mother bought for our ranch, she had to specify whether she wanted a radio or a heater. Now, the vehicle changes your mood.”

FABULOUS TECHNOLOGY

Similar technology may be used to improve animal management, Catlett says. “Farm animals have a fabulous life. They have all their needs take care of. Then they have one really bad day.” Technology will help producers manage animals and keep them comfortable and cared for.

The switch from reliance on taxicabs to Uber transportation may make it to Rural America. “Can we use that principle for on-farm grain storage? Get ready for Uber everything; smart devices will change everything.

“The technological revolution is also helping people to learn. Education is a continuum.” But that’s not new. “When Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia, he didn’t permit degrees. Degrees represented an end.” He says modern education may mimic that foresight. “We will get an education, but in a lot of different ways.”

The fourth trend is based on a new material, graphene, an extremely strong substance with countless potential uses, including in a new, more efficient means of extracting hydrogen from water. “3-D printing is changing the face of manufacturing. Manufacturing is coming back to the United States. Bio-printing is another avenue.”

One company, he says, is offering a Methuselah Prize — $1 million to the first person to “print” a liver, put it into a large animal, and keep the animal alive for 90 days.

Graphene is the medium for 3-D printing, and researchers have already printed 3-D hamburger meat. “Will 3-D printing replace food production? No, but it could have a fit in some cases. Farmers will continue to produce the raw products.” Other potential 3-D printing applications include health foods and vaccines.”

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Singularity, he says, is the fifth trend — when the gap between human intelligence and artificial intelligence becomes even narrower. Some predict that by 2029 artificial intelligence will exceed human intelligence.

“I don’t know if we will ever have something smarter than a human,” Catlett says. But, he does believe technology will create more opportunity than it displaces. “The fear of no jobs in a world where robots can already reproduce themselves 100 percent likely will not stand up to scrutiny. Technology already creates more jobs than are lost to it. Technology creates more economic activity.” That could be a positive development for Rural America.

The sixth trend, he says, involves social interactions, and it’s an area where men can learn from women, who are much more likely to develop deep social connections. “Studies show that people with deep social connections die from all causes at only one-fourth the average rate. If they don’t have deep social connections, people die at four times the average rate. People matter. People matter to agriculture. It’s part of our DNA— people need people.”

Studies also show that a person who comes into contact with someone he or she likes will undergo changes within 30 minutes that help restore the immune system. “In the presence of plants, the change takes about 20 minutes. It also works for animals.”

Catlett closes this, and most of his presentations, with a story about the last days of a beloved dog. The veterinarian told him and his wife that the only thing they could do was to take their pet home, keep it comfortable, and love it.

“When we saw our pet was in distress, we’d sit in the floor beside him, and within a few minutes his respiration would slow and he would calm down.” They did that — taking turns, or being on the floor with the dog at the same time — until the animal died peacefully.

Catlett makes the point that even with technology, relationships — human to human, human and plants, and human to animal — remain strong, positive factors for health and well-being. And that, despite the sinking commodity markets, droughts, and hardships of farm life, is why “it’s a great time to be in agriculture.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like