Seven years ago we asked Purdue ag economist Chris Hurt to shed light on where corn and soybeans were at in the long-term boom-bust cycle. With a few exceptions, these cycles last about 29 years.

This update is one of those “you are here” maps.

Everything in this story needs a disclaimer, Hurt warns. These are just the educated opinions of some folks who have taken a good look at the long-term picture. So take these projections with a grain of salt.

Based on the current price cycle that started in the mid-1990s and peaked in 2012, row crop agriculture still has two or three more years of pain — deflated prices, sticky costs and tight margins — as global supplies and production remain plentiful.

The good news? Demand remains solid, and the cost of money, while rising, is still reasonable. Farmers still have solid debt-to-asset ratios.

“This is a moderation cycle, not a bust,” notes Hurt. “In the ’70s, we built up a lot of export demand that went bust, and that was one of the impacts you saw in the ’80s, compounded by extremely high interest rates. It was debt that caused that crash.”

The cycle explained

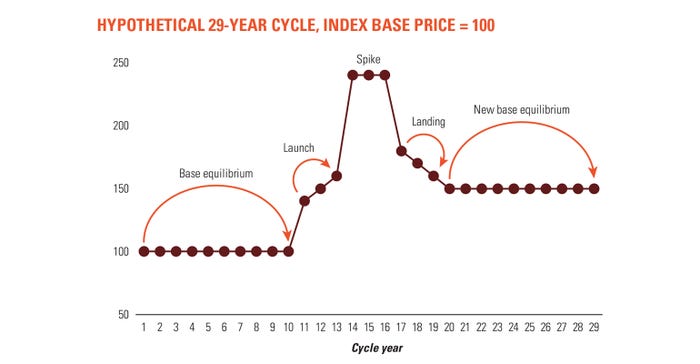

In general, grain prices stay relatively low over time due to excess supply compared to demand — with a few glorious exceptions. Hurt has identified four distinct 29-year time periods (see above), where world or national events caused a price run-up, brief peak period, a cooling-off period and an eventual new base.

“Over the course of those 29 years, farming is tough, then interesting, then wonderful, then scary, then tough again,” says Hurt.

It’s “tough” because prices crash far faster than costs adjust. That’s the norm. Iowa State University data shows that input costs take five or six years to adjust after prices collapse. Prices for corn, wheat and soybeans adjust overnight to market supply-and-demand conditions.

Think about how quickly a piece of weather information drives price, and price drives revenues.

Costs don’t adjust as fast for several reasons. In one year, if farm returns increase $100 an acre, next year about $10 of that might get bid into cash rent. Most farmers would not automatically bid all that $100 into next year’s cash rent, because they need a series of positive market indicators over time before new confidence results in higher land bids.

One reason it’s so difficult for land costs to adjust downward is competition. Tenants are anxious about protecting their land base. They have fixed overhead costs like machinery, storage and families to feed. So losing land is a risk they don’t want to take.

“That fixed overhead investment is what largely makes it difficult to get rents to adjust downward,” says Hurt.

Grain Price cycle

Here’s how a typical grain price cycle might look:

base equilibrium price — around 10 years characterized by tight margins and low volatility

launch price — around three years characterized by slightly better margins and growing demand compared to just adequate supplies

spike price — around three years characterized by high prices and great margins, spurring higher production

landing price — about three years where resulting oversupply catches up with demand and prices fall

new base equilibrium price — around 10 years characterized by prices leveling out, usually higher than the original base price

Price drivers

Prices tend to cycle up and correlate with major world events; 1917 (World War I), 1947 (WW II) and 1974 (Soviet grain purchases) were all peak price years. The latest was 2012, fueled by ethanol and Chinese imports, which were both compounded by drought.

“In 1947, we were already tight on stocks and we had horrible growing conditions, so we had a price spike,” Hurt says. “In the late ’60s, we had pent-up demand and one of the best corn price years ever in 1974.”

Seven years ago Hurt believed prices were about to peak and head for a landing period. He predicted that by 2017 we would be in the middle of a new base equilibrium price that wouldn’t change much from 2013 through 2022.

Looking back, his analysis appears spot on. But where will prices eventually settle in this cycle?

If you look at the three cycles since 1903, prices were 41% higher in the launch, 243% higher in the spike, 62% higher than the base in landing and then settled at 50% higher in the “new” base compared to the original base price (adjusted for inflation and yields).

From 1998 to 2005 — the early years of the current cycle — corn prices averaged just over $2 per bushel. Corn prices have hovered between $3.50 and $4 in recent years.

Today Hurt and his colleagues have run the numbers and conclude that average farm returns will remain negative in the short term, possibly through 2019.

Of course, any black swan event can come along and upset this analysis.

“One of the dangers of doing year counts is that these patterns occur over time, but it’s the conditions within each of those cycles that you can’t predict,” says Hurt. “If we got into a shouting match with China over North Korea and they dramatically cut soy imports, we’d be in big trouble.

“We’re now in the fourth year of downside adjustments,” he adds. “We’ve said four is a minimum, but five or six is possible. The long-term pattern is that you go into the down period and expect a long period with tight margins.

“Boom years are the exception, not the rule.”

Market-based capitalism

During boom years when demand strengthens, grain prices shoot up and costs lag, resulting in huge margins. During the drop, it’s just the opposite, so revenues plummet. Costs feel almost locked in, but they do come down eventually.

In market-based capitalism, there’s a period of financial pain that has to ensue. That same process is going to happen on the upside, but when it’s on the downside, revenues fall like a rock and costs seem like they are high and locked in.

That’s the period farmers have to get through — that landing period. Which is why magazines like Farm Futures keep yammering on about costs. It’s really the only way to change your financial picture if you’re working in the commodity cycle.

Yes, prices may move higher. But the “actionable” tasks are on the cost side. Focus on efficiency and lower family living costs. Every purchase needs an ROI, every asset needs to pull its weight. Off-farm income will play a bigger role.

“Tight margins, high knowledge levels, super efficiency, lower costs — that describes agriculture most of the time since the ’50s,” says Hurt. “There are a few exceptional periods, but most of the time you have to be pretty darn good at what you do, have a modest lifestyle and be an attentive businessperson.

“That’s what most businesses should be — driven to be good at what they do.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like