November 4, 2021

As 2021 winds to an end, farmers and ranchers in Nebraska and across the U.S. are assessing a mix of favorable trends in farm income and finances, but also significant questions about future income prospects and policy directions.

Farm income results

Since the recent low of $62 billion posted nationally in 2016, U.S. net farm income has grown to a projected $113 billion in 2021, according to USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) estimates published in early September.

The 2021 projection would be near record levels for farm income (in nominal terms), surpassed only by a similar 2011 level and a 2013 record of nearly $124 billion. The rebound since 2016 may seem all the more surprising given the negative impacts of trade conflicts in recent years and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (and continuing). Hidden behind the numbers, however, is the significant role played by government payments to producers.

Net farm income minus government payments actually fell year over year from 2018 to 2020 as trade losses and COVID-19 pandemic effects were felt. However, government payments grew from less than $14 billion in 2018 to more than $45 billion in 2020 as trade assistance and then COVID-19 assistance mushroomed.

In 2020, these supplemental and ad hoc assistance payments represented more than 75% of all government payments, overwhelming traditional sources of government payments from commodity programs ($6.5 billion) and conservation programs ($3.8 billion).

This growth in government payments, primarily through supplemental and ad hoc programs, also substantially increased the total share of net farm income coming from government payments from less than 20% in 2018 to nearly 50% in 2020.

A robust turn in commodity markets in late 2020 meant a substantial rebound in market income for 2021. By that point, however, much of the COVID-19 relief was committed, meaning that government payments continued even as market income increased.

The near-record projection of $113 billion net farm income for 2021 is built on sizable projected gains in crop and livestock receipts of 16% to 20% over 2020, while farm expenses were projected to rise less than 10% relative to 2020.

Projected government payments shrank dramatically from 2020 to 2021, but still came in at a projected $28 billion as the COVID-19 relief continued to roll out and dominate government payments to producers. In fact, with higher prices, projected commodity program spending fell to only $3 billion for 2021.

While the aggregate numbers hide the significant challenges that some sectors and regions have faced over the past year or more, the overall farm income prospects paint a solid financial picture for most of agriculture, even if it has come on the back of substantial government support.

Nebraska numbers

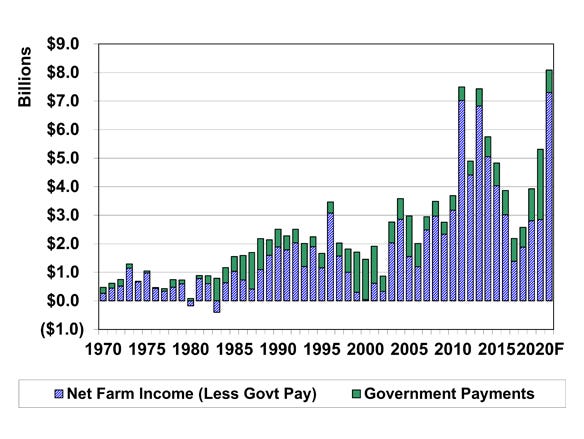

Looking specifically at Nebraska, the USDA-ERS projections showed a $5.3 billion net farm income for 2020, more than double the recent low of $2.2 billion in 2017. As with national numbers, much of the growth in income has come from larger government payments, which grew from $800 million to almost $2.5 billion over the same time period because of the trade and COVID-19 assistance.

Using the USDA-ERS numbers as a base, current projections suggest Nebraska net farm income could exceed $8 billion for 2021. That would be a record, eclipsing the previous mark of $7.5 billion reached in both 2011 and 2013 (again, all in nominal terms).

Farm income prospects

The near-record farm income projections nationally and record projections for Nebraska for 2021 are largely a product of the strength in most commodity markets, along with smaller but continuing ad hoc government payments. The projections for 2022 face a harsher reality of lower projected commodity prices, higher projected input costs and substantially lower government payments.

While still strong relative to recent years, projected crop commodity prices for 2022 and beyond are substantially lower than the highs of 2021. Recent baseline projections from the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri suggest marketing year average prices for major crops could fall 10% or more.

That would pull crop receipts down substantially, even accounting for presumed productivity gains. For livestock, prices are projected slightly higher for dairy and beef, but slightly lower for poultry and eggs and substantially lower for pork, leaving overall livestock receipts similar year over year. Adding in other farm income, total value of production could be down a few percentage points in 2022.

The real challenge may be on the input side. While purchased feed and livestock should mimic commodity price movements, manufactured inputs look to be substantially higher. The same FAPRI projections suggested about 10% increases for seed, fertilizer, chemicals and energy. Readers may even question those projections given discussion of price quotes or lack of price quotes and quantities, but it seems certain that the cost side will be a challenge in 2022.

Analyzing estimates specifically for Nebraska, the combination of lower crop commodity prices and substantially higher input costs will squeeze farm income. At the same time, projected government payments continue to decline with the presumed end of COVID-19 assistance and only conservation programs, minimal commodity programs and some disaster assistance expected.

Just as no further COVID-19 assistance is expected, no additional support as suggested in infrastructure or spending proposals is assumed unless and until it is actually passed.

Putting lower crop prices together with higher input costs and lower government payments, farm income in Nebraska in 2022 could fall quickly from the record $8 billion level projected for 2021 to less than $6 billion in 2022 before moderating.

Farm income near $6 billion would still be stronger than in recent years when it was below $4 billion (2016-18), but it would be a substantial downward adjustment and a continuation of recent volatile market and income trends.

Policy prospects

Just as the farm income situation has been volatile and difficult to predict, the ag policy outlook has also been difficult to project. The stronger crop commodity prices could drive projected farm program payments down to the point that there is a relatively small commodity program baseline budget heading into the presumed 2023 Farm Bill debate.

That could make it extremely difficult to enact any desired changes in farm programs. Conversely, it could make it relatively easy to simply keep the status quo in place and move forward with the same Agriculture Risk Coverage and Price Loss Coverage programs.

Conservation programs have become as prominent as commodity programs for the moment in terms of expected payments, and the ongoing infrastructure spending debate has proposed substantial increases in conservation spending targeted to climate priorities.

Whether that comes to pass or not, conservation spending will certainly be a major priority for the next farm bill debate. That leaves crop insurance as the other major part of the farm portfolio in the farm bill.

Crop insurance spending doesn’t receive the same attention annually as premiums and indemnities don’t show up on the government payment line, but government spending on crop insurance support (premium subsidies, company and government administration, and reinsurance) is substantial and has been a regular budget target in appropriations and farm bill debates.

Beyond the farm policy debate, there is as much or more uncertainty at the moment over tax policy, trade policy, bioenergy policy and regulatory policy as there has been for farm income prospects. Each of those policy areas can affect the bottom line for agriculture substantially and arguably even more than some of the farm policy choices to be made in the next farm bill.

Keeping an eye not only to markets and inputs, but also to policy developments will be critical to assess the real outlook for agriculture in 2022 and beyond.

Lubben is the Extension policy specialist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like