For Mississippian Brad Spencer, ‘farming’s what I’ve always loved’

Brad Spencer's farming accomplishments, his community service contributions, and his involvement in state and national agricultural issues were factors leading to his being named this year’s Outstanding Young Farmer/Rancher by the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation. He placed in the top 10 in the national competition at Honolulu.

When Brad Spencer realized his destiny was to be a farmer, not a veterinarian, he came back to the family’s Mississippi operation to “rejoin the life I’d always loved.”

He had gone to community college to play baseball, another love, with an eye toward an eventual veterinary medicine degree. But fate stepped in.

“Our key employee back at the farm left, and I began commuting back to the farm to help out. Before long it dawned on me that I loved farming more than I did school — that there was no life I wanted more than farming.

“So I came back, married Carla, who I’d met at school, and have never regretted for a minute not becoming a veterinarian.”

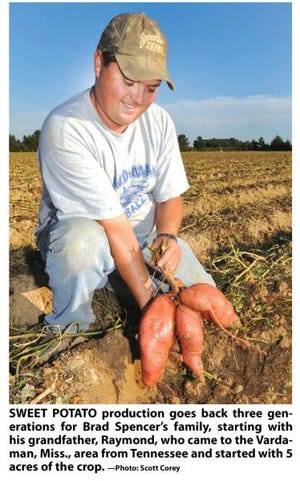

He began farming with his parents, Keith and Barbara Spencer, and rented five acres to farm on his own — a historical mirror of his grandfather’s start in farming decades ago here at Vardaman, Miss., the epicenter of the state’s thriving sweet potato industry.

“Grandfather Raymond Spencer came here from Tennessee, bringing sweet potato seed with him, and started farming on just five acres. He paid $25 an acre for the land — now, you couldn’t buy it for $2,500 an acre. My father continued the operation and expanded it, adding a packing shed for washing, grading, and storing potatoes.”

Today, Brad has boosted his owned acreage to 60, and is 50-50 partners with his father in the 1,700-acre Spencer and Son operation that includes sweet potatoes, peanuts, soybeans, and wheat.

He has a 50-plus cow herd, and 20 acres of watermelons that he says are a college fund for sons, Hunter, 11, and Justin, 8, who help with related chores, “to teach them responsibility and decision-making and to give them some of the training and experience I had growing up on a farm.”

Brad and Keith are expecting to rent more land this year so they can add to their peanut and sweet potato acreage, he says.

“If that works out, we’ll have another 300 acres, and our crop mix will likely be 600 acres of sweet potatoes, 700 peanuts, 20-30 acres of watermelons, and the rest in soybeans. We rotate land between crops to keep down diseases, and the 400 acres we have in winter wheat could go back into potatoes.

“Dad pretty much looks after the peanuts, and I take care of the other crops and the cows. My mother handles payroll and recordkeeping, and when were going full speed with harvest, she’s out there driving a tractor.” Wife Carla is a teaching assistant at a local school.

Brad’s farming accomplishments, his community service contributions, and his involvement in state and national agricultural issues were factors leading to his being named this year’s Outstanding Young Farmer/Rancher by the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation. He placed in the top 10 in the national competition at Honolulu.

The Spencer farming operations are spread across a 45-mile radius in Calhoun and Chickasaw Counties, which necessitates a lot of tractors — “We have 11, not counting the time I got on the John Deere and Kubota tractors that were part of the Farm Bureau award,” Brad says. “It’s an hour’s tractor drive to the farthest field.

“Dad and I bought a 30-foot no-till drill last fall and will now do a lot of no-tilling of soybeans. The John Deere (award) tractor has a guidance system on it, which will improve efficiency and save time.”

Yields on some of their soybean fields have topped 55 bushels, with an average across all their acres of 35 bushels.

Irrigation not feasible

“All our crops are dryland — we’d have to drill so deep here for a relatively small volume of water that it just isn’t economically feasible to irrigate. So,” he laughs, “we do a lot of praying for rain.

“But, if we can get enough rain to get them up and growing, sweet potatoes and peanuts can get by with less rain water other crops. If we can catch a shower now and then during the growing season, we’re OK. The potatoes are actually sweeter when the weather’s a bit on the dry side. Too much rain will rot them; they just turn to mush — as happened in the record rainfall year of 2009, when we lost 200 acres of potatoes and 100 acres of peanuts.”

Until 1995, the Spencers also grew cotton, but that year Brad says “the bugs ate up the crop, no matter what we sprayed, and potatoes ended up paying the bills for the cotton. We haven’t grown any cotton since.”

Sweet potato production in the Vardaman area continues to grow, Brad says, with expansion into neighboring counties and good demand in both fresh and processing markets.

“The increased emphasis on healthful foods has been a boost,” he says. “Sweet potatoes are high in Vitamin A, beta carotene, and a number of beneficial anti-oxidants and anti-inflammatory nutrients. Even with all the production in this area, there’ll be the occasional year when demand can’t be met and the brokers have to buy potatoes elsewhere.” (North Carolina is the leading sweet potato state.)

They shoot for yield average of 400 to 500 bushels per acre, with 260 bushels of that for consumer field packs. There are three grades: No. 1, No. 2, and Jumbo; those that don’t fit into those grades are processors. No. 1s are the most profitable.

Unlike other row crops that utilize a lot of mechanization, sweet potato production, is very labor-intensive, Brad notes.

“About mid-March, we’ll take whole potatoes from the previous year’s crop to use as seed. (Every two years, we buy some new seed potatoes in order to keep diversity in the gene pool.) We put the seed potatoes in prepared beds, cover them with both black and clear plastic to retain heat, and in three to four weeks sprouts will be pushing up the plastic. We take off the plastic and cover the beds with a mesh fabric that allows water and air penetration, but also helps hold heat.

“Four weeks later, when the sprouts are about 6 inches high, we go in with a blade harvester and cut them off the mother potatoes. We hold them for a couple of days until they begin forming little white roots and are ready for planting.”

Every plant is put into the ground by hand. “We have 8-row and 4-row potato setter machines, which workers ride through the field, placing plants into the soil. Sixteen people ride on the 8-row machine, with four walking behind, and there are 12 people with the 4-row machine, so we’ll have 32-people in the field for planting. We can plant about 30 acres a day.

“We can’t no-till potato ground; they need good, loose soil for planting and harvesting, so we have to till the land well.”

Poultry litter for fertility

Brad says he’s “a real believer” in soil sampling to determine fertility needs; “it’s a proven practice for us.” For the past five years, they’ve been increasing their use of composted sawdust poultry litter, and “it has worked really well, both in terms of fertility and adding organic matter. We’ll apply an average 1.5 tons per acre and, if soil tests indicate, we’ll also add some commercial 9-23-30.

“I can tell to the exact row where I’ve used the poultry litter — the plants are more lush and have a richer, deeper color.”

They plant two varieties, Beauregard and O’Henry, the latter a white sweet potato for a limited market; “we only plant 15-20 acres,” Brad says, “but they’re a really good money variety.”

For the first 40 days, he handles weed and insect control; when the crop starts putting out runners and enters the vigorous growth stage, his consultant checks once or twice a week for insects, including cucumber beetles, flea beetles, wireworms, and cutworms.

Other destructive pests, he notes, are deer and wild hogs. “Deer just love potatoes and will paw them out of the ground, and the hogs will root them up. They’ll also get into the watermelons, but they don’t bother peanuts as much.”

Harvest, also labor-intensive, starts about 90-120 days after planting, usually around Aug. 15, and continues until November, six days a week.

“We can harvest about 15 acres a day. I do as much separating and grading as possible in the field, which makes things easier once we get potatoes into the packing shed. The potatoes are loaded in wooden boxes and stacked on an 18-wheeler trailer to haul to our shed, where they’re stacked in temperature-controlled storage until they’re cured (about four to six weeks), after which they’re washed, graded, and packed.”

Brad admits to being “a hard man to work for when it comes to grading — that’s where I really watch things closely, because I want to be sure the very best quality product possible goes to my customers.”

Each year, he says, “Our goal is to be ready for our biggest sales period, Thanksgiving. The second biggest sales period is Easter, with Christmas ranking third.

“We sell both to brokers and to our own customers, as well as to walk-ins and peddlers. Whatever the customer wants, we try to provide it.”

In addition to boxed and bulk potatoes, the Spencers process a lot of three-pound bags for special orders, and can do about 600 of those per hour.

“We can keep 15,000 bushels of potatoes in storage, at 55-60 degrees, the year-round,” Brad says, “but our every-year goal is to be sold out of the old crop just about the time the new crop is being harvested.”

Culls or junk potatoes are sold for feed for cows — “they really love ‘em; when I go into the pasture with a truck full, my cows come lickety-split.”

New packing facility

In between rains since last Thanksgiving, Brad has been trying to get work under way on a new packing facility just up the road from his house, “so I can keep a closer eye on things.”

It will be a 120-foot by 180-foot building, with areas for washing, packing, and storage. “With all of the new rules and regulations we have to follow, it would take too much money to upgrade our current packing facility, which is the oldest in Vardaman. But we will do some renovation and continue using that facility for storage. The new facility will allow us to consolidate our operation and to achieve more efficiency.”

Sweet potato acreage is increasing in the region, he notes, in order to meet growing demand and also, “a lot of cotton growers have added sweet potatoes to their crop mix because of the rotational value. And because of their high fertility requirement, there is some residual fertilizer for the following cotton crop.”

Last year, the Spencers had 300 acres of peanuts. This year, with high prices as a result of the 2011 drought in Texas that sent prices zooming, Brad says, “We’ll have at least 500 acres, and if I can buy or rent another combine, we’ll go as high as 750 acres.

“Peanut contracts had been in the $350 per ton range, but when the drought hit last year we contracted ours at $650, which was $100 more than we’d ever got before. And for peanuts over our contracted amount, we got $1,000 per ton.”

They plant the Georgia Green variety in 40-inch rows when the soil temperature is about 70 degrees. “We don’t plant them more than two years on the same ground, and then we’ll plant something else there for three years in order to avoid disease buildups. We use a consultant on peanuts from Day 1 to check for diseases, particularly white mold.

“We shoot for a 3-ton yield and average around 2.5 tons, depending on weather. All our peanuts go to a buying point at Aberdeen, Miss.”

Mike Howell, Mississippi Extension peanut specialist, says the state’s farmers could more than double plantings this year, to about 30,000 acres.

This is Brad’s third year for his sons’ college fund watermelons.

“The first year, they did very well,” he says. “The second year was average, and last year was pretty much a disaster due to dry weather — the melons just rotted.

“Once we destroy the beds where we start our sweet potato plants, we plant watermelons there, about the end of May or first of June. They’re ready for harvest about the first of September, when other producers are starting to wind down their summer production.

“It’s not a prime time price-wise for watermelons, but it’s still good money. In a good year, we’ll get 2 tons to 3 tons per acre. These late melons are exceptionally sweet, and we sell all we grow locally or to peddlers who come to the farm.”

He started his sideline cow operation, also for his sons’ college fund, with five head, and now has 57.

“We got in just the right time,” he says, “because beef prices have seen a really good increase. Money from the cows we’ve sold has already paid off a good chunk of the loan at the bank.”

In addition to his farming, community, and church activities, Brad is a member of the board of directors of the Sweet Potato Council and the Sweet Potato Council Fruit and Vegetable Co-op, and has served as vice chair of the Mississippi Farm Bureau Sweet Potato Commodity Advisory Committee.

He says farmers in the area are a close-knit group. “We all help each other. If I have a slack period and one of the other growers needs some help, I’ll take my crew and help out. Last year, I took my entire operation over to help a neighbor, and I know he’ll do the same for me if I need it. We all have a really special bond, which has made my choice of a farming career all the more meaningful.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like