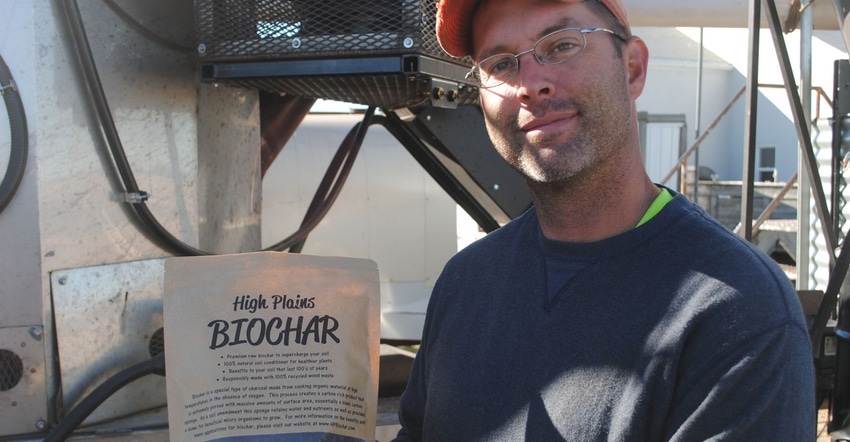

Rowdy Yeatts didn't grow up in Nebraska and he didn't come from an agriculture background. However, what Yeatts and his wife, Christi, are working on at their homestead south of Chadron could have wide impact on Nebraska farmers and ranchers.

They are making a biochar product called High Plains Biochar. With their mobile unit, they process woody products and wood waste into a form of black carbon. He partnered recently with the Nebraska Forest Service and the University of Nebraska to study the potential health benefits of feeding small amounts of biochar to livestock. There is also some evidence that biochar treatments can help improve soil health properties when used as a soil amendment.

"We've all made biochar before, whether we knew it or not," Yeatts says. "That charred wood residue left after a campfire that is light and easily crumbles is biochar." It has been used as a soil amendment for thousands of years, he says.

In Yeatts’ system, rough woody waste and chips are ground to a uniform size with a small tractor-driven grinder and transferred to a holding bin. From the bin, the wood chips are augered into a 1 million-Btu boiler, which takes woody waste chips up to 1,700 to 1,800 degrees F. The chips are stirred within the furnace cavity during heating, and the final biochar product is augured into large sacks for shipping. The boiler unit is produced by LEI-Products based in Kentucky. According to Yeatts, the company produces biomass boilers for heating purposes, but they were able to modify his unit to produce biochar.

"I would like to be able to take this mobile unit to the woods or any location where there is woody waste products and process it there," Yeatts says. "Because of the water content in the woody waste, we could probably reduce the production cost by 80% by taking the unit to the source and making biochar on location and haul the final product away, rather than hauling the waste or slash piles to one location."

Red cedar control

With red cedar encroaching prime grazing lands across Nebraska, Yeatts sees this biochar production unit as one way to use a growing cedar resource, as well as other slash piles or woody waste. Right now, his unit runs 24 hours a day, seven days a week at his home site. "Everything is automated, so the unit has automated shutdown if something goes wrong," Yeatts says. "I fill up the bin, and it usually takes about five hours to empty."

He has also experimented with bone biochar, learning more about the potential to make biochar from livestock mortalities. With his background in the construction business, Yeatts recently built a larger stationary unit with a bigger holding bin that will be more automated than his mobile unit for onsite processing.

According to UNL animal science research assistant professor Andrea Watson, Nebraska Forest Service foresters, Adam Smith and Heather Nobert, originally brought the idea of producing biochar and information on potential benefits to researchers. "They have been advocates of value-added wood-based products in the state and have been very supportive of this project," Watson says.

Previous research feeding biochar to cattle suggests that it can inhibit methane production and improve feed efficiency for cattle on low-quality forage-based diets, Watson says. Cattle feeding trials in Southeast Asia observed a 22% reduction in methane production with a concurrent increase in cattle efficiency with a small increase in weight gain with similar intake for cattle supplemented with biochar at 0.6% of diet dry matter daily. But no similar studies have yet occurred in the U.S. That's why Watson and other researchers at UNL began planning their own feeding trials.

The potential benefits are noteworthy, Yeatts says. If these biochar feeding benefits are proven through further UNL studies, the potential is there to not only have a way to use red cedar and other woody waste in a useful manner, but to also reduce methane production and improve cattle feeding efficiencies at the same time, he notes.

You can learn more by going online at hpbiochar.com or by calling Yeatts at 308-430-8213.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like