March 7, 2022

In a field of knee-high grass in the Flint Hills, Bill Browning teaches his young grandchildren the names of plants, birds, and bugs. Bill and his family have spent the past half-century caring for their 115-year-old working ranch near Madison, Kan.

Part of their passion for conserving the prairie comes from the loyalty the Brownings feel toward the critters that live here, including the 60-plus prairie chickens that boom from their pastures each spring.

“With taller grass and less trees, the birds have more places to nest,” points out Carson, Bill’s 13-year-old grandson. Carson enjoys going out with his Papa on the four-wheeler to spray herbicide on any tree seedlings invading their grasslands.

The Flint Hills of Kansas boast some of the last intact tallgrass prairie in the world. But like most grasslands across the Great Plains, this rich grazing land is threatened by a “green glacier” of encroaching trees that diminish the prairie’s productivity for wildlife and livestock. Thanks to the Brownings’ dedication to maintaining weed-free, tree-free grasslands, the waving stems here support cows and wild critters alike.

“I’m proud of the fact that I’m standing here in a broad area that is pretty much free of invasive species,” Bill says. “There are no trees within hundreds of yards.”

Initiative

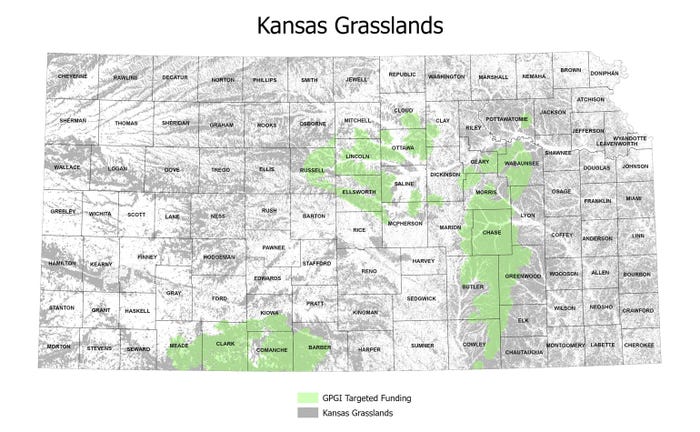

Last year, the Brownings were the first landowners to receive assistance as part of the Kansas Great Plains Grassland Initiative, which provides ranchers financial and technical support to keep invading trees at bay. GPGI is a rancher-driven, science-informed, and agency-supported effort that seeks to defend and grow intact grassland cores by reducing vulnerability to woody encroachment. This initiative is part of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Working Lands for Wildlife, the agency’s premier approach for conserving America’s working lands to benefit people, wildlife and rural communities.

Luke Westerman, a Kansas NRCS employee who has worked with the Brownings since 2005, says that woody encroachment is one of the top concerns facing the Flint Hills.

“We are absolutely losing the prairies to woody encroachment,” Westerman says. “If we allow trees to take out even an acre of grassland, then we lose that acre for cattle grazing. The goal of the GPGI is to create open prairies for the long term by removing both young and mature trees.”

Through the GPGI, Westerman helped the Brownings evaluate their pastures to inventory woody encroachment. This entailed using a skid steer with a saw to cut down bigger trees, and using a pump sprayer to spot-treat small seedlings. The GPGI also includes financial assistance to monitor encroachment for a few years post-treatment to make sure no new trees sprout up.

Embrace controlled burns

Another way to ensure the prairie remains tree-free is to burn it frequently. Like many of their neighbors in the Flint Hills, the Brownings embrace fire as a way to generate productive grazing pastures with high-quality, nutritious plants for cattle.

Historically, the Great Plains would burn every few years, which kept trees isolated to fire-shadow areas. Suppressing fires has inadvertently given the upper hand to woody species, slowly turning prairies into forests.

The Brownings’ daughter, Elizabeth Kusmaul (Carson’s mother), lends a hand during burns.

“If it doesn’t burn, we get a lot of ugly things coming up, things the cattle don’t want to eat, including hedges and trees,” explains Elizabeth, who has lived on or near the Browning Ranch her whole life.

The future

A second-grade teacher in Madison, Elizabeth brings her students to the ranch to learn about the prairie.

"We want to make sure this area doesn’t disappear on us, to keep it around for the younger generations.”

The GPGI has been a boon for conserving the Brownings’ pastures. Launched in March 2021 by Kansas NRCS, GPGI has issued 63 contracts, totaling nearly 100,000 acres of native prairie in core grassland regions in the Flint Hills, Gypsum Hills and Smoky Hills. The program committed an initial $3.9 million to help these ranchers and landowners tackle woody encroachment. For interested landowners, NRCS can also provide technical assistance to evaluate pastures — no commitment required.

“The No. 1 economy in Greenwood County is cattle ranching. If we want to see that economy survive and keep the ecosystem intact, then it’s important to keep these prairies open,” Westerman says.

To learn more, call 785-823-4500, or visit bit.ly/gpginit.

Randall is a writer, communications specialist and adventurer based in Missoula, Mont.

Source: The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS) Working Lands for Wildlife is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like