Alfalfa weevil is the most abundant pest at this time of year, but it is hard to predict where it will show up and how much damage it will cause.

Alfalfa weevil is actually an invasive insect, says Kevin Rice, University of Missouri entomologist. “It was accidentally introduced to the United States about 120 years ago, and it's been here so long that it doesn't really behave like some of our newer current invasive insects because the USDA released a lot of parasitoid wasps and viruses that actually helped keep it in check, and lowers down the population," he says.

But because it's an invasive species, it has very patchy distribution and doesn’t reach economic threshold levels in every field every year. “You may have a higher problem and a higher population than your neighbor down the road,” Rice says. So, farmers need to scout fields on a weekly basis.

Signs of a weevil

When scouting for this weevil, look for its distinct black head. It also has a prominent white line down the middle of the back and a less distinct line along the side of the body. They are legless and about a quarter-inch long.

In May, farmers are mostly seeing the second instar of alfalfa weevil. Some of the early signs, Rice says, can be seen on the plant foliage. “You see small little circles, and that's probably going to be your first clue that you have a growing population of alfalfa weevil in your field,” he says. Then it is time to scout.

BULLET HOLES: Alfalfa weevils tend to eat in a circle and often look like small bullet holes in the plant leaf.

Determine insect infestation

Farmers can use a sweep net to scout initially and see if larvae are present, Rice says, but determining threshold levels requires a little more detail.

Start by collecting 10 stems and break off or clip them over a bucket. “You want to do this in five locations throughout the field,” Rice explains. One thing to remember is to hold the bucket over the stem before breaking it, because the larvae do have a response trigger. “So, if you start shaking that too much, they'll drop off before they make it in the bucket,” he adds.

The action threshold for Missouri is when collections — 50 stems at five locations — have an average of one or more larvae per stem. That signals that the alfalfa weevil is present and causing damage. However, hay fields can vary in quality, leaving farmers to question if the treatment for this insect will actually pay dividends in the long run. For that answer, Rice says farmers should consider the dynamic threshold.

Insects cost money

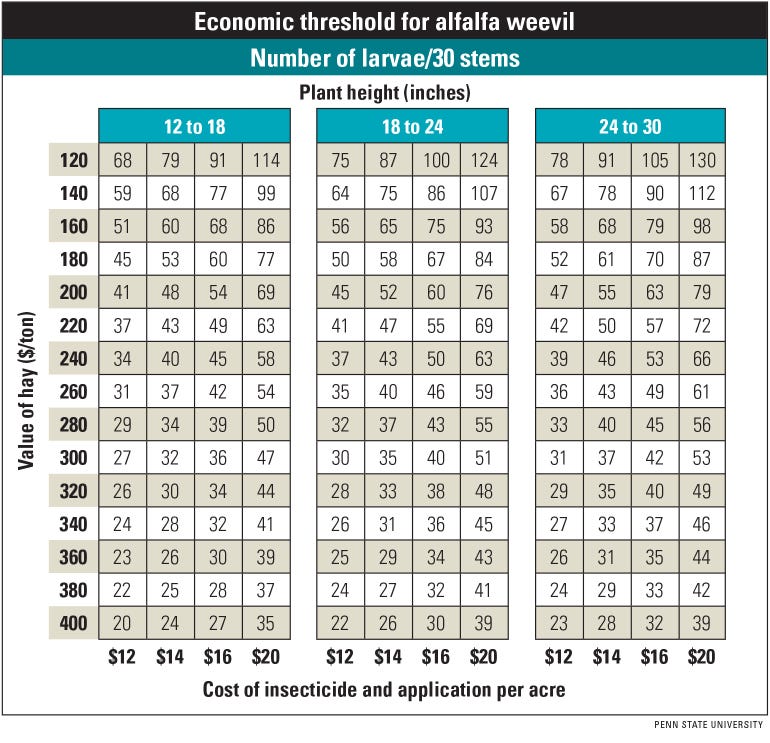

A dynamic threshold considers the value of hay and the cost of treatment at different plant heights to determine overall economic returns. Penn State University developed a guide for farmers as seen below:

“Basically, you want to look at the height of your plant, which is the three columns, and then you're going to look at the estimated value of your hay on the left-hand side,” Rice explains, “and then you move across and basically the cost of your insecticide application is on the bottom. That's going to give you the number of weevils that'll be your action threshold.”

The chart was developed for 30 stems, collecting at three sites. Rice says it's a little more complicated, but it's a lot more accurate on economic value. “It will tell you whether you're going to get your money back on that spray application," he says.

Weevil management options

Other than spraying fields with insecticides, Rice says if farmers hit action threshold, early harvest is a good management option. “It will take out about 95% to 98% of the beetle larvae,” he notes. “It'll remove them from the field and kill them.”

He also noted that bait traps are “pretty effective” at knocking down alfalfa weevil populations.

Rice stresses that farmers should wait until the pest reaches thresholds because the natural enemies in the field, if they're working, they can dramatically reduce the population.

Tracking pest movement

The University of Missouri is tracking movements of pests across the state through its Pest Monitoring Network.

Rice says there are a number of traps set up across the state. “We are tracking and have a grid of traps that are monitoring pests on a weekly basis,” he notes.

The university is tracking six insect species — brown marmorated stinkbug, black cutworm, corn earworm, fall armyworm, true armyworm and Japanese beetle. Rice says the reason for tracking these species is because they are migratory, and there is no good model to determine when they arrive and their movement in the state.

Farmers can sign up through MU’s Integrated Pest Management portal to receive email alerts on when these pests arrive in their area. People can opt to track one or more pests.

Early notification allows farmers to increase crop scouting and plan treatment. For more on the MU Pest Monitoring Network, visit ipm.missouri.edu.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like