October 10, 2018

By Chris Torres

While spotted lanternfly has mostly been seen in eastern Pennsylvania counties, it is spreading fast to other counties and is feeding heavily in orchards and vineyards.

"Right now, we are seeing spotted lanternfly feed heavily on grapevines and apple trees," says Heather Leach, the spotted lanternfly educator for Penn State Cooperative Extension. "In grapes, we are seeing significant damage resulting from last year's feeding, but to date no damage has been reported in tree fruit.

"In grapes they consistently feed, which we believe is causing issues with overwintering and the following year's fruit set."

Leach says the challenge to controlling its movement is that it's a good hitchhiker, attaching itself to packages, cars or other things that will move it to another place.

Breeding for next year

All lanternflies are in their adult stage right now, and females are laying eggs on hard surfaces such as trees, stones, fences, fence posts or vineyard posts.

Once egg masses start appearing they can be scraped and smashed.

Female lanternflies lay two egg masses for a total of between 100 and 120 eggs. While lanternflies only have one generation — by comparison, spotted wing drosophila can produce up to 10 generations per year — the main concern is that it can attack up to 70 different plant species, including corn and soybeans, with preferred hosts being the Tree of Heaven, grapes, black walnut and hops.

MOSTLY ADULTS: Spotted lanternflies are currently in the adult stage with females ready to lay eggs.

MOSTLY ADULTS: Spotted lanternflies are currently in the adult stage with females ready to lay eggs.

Leach says growers can spray if they see heavy egg populations of the pest, but another option might be tree banding, especially around Tree of Heaven, which involves placing a sticky band around the circumference of the tree where the spotted lanternfly gets stuck and eventually dies.

Concerns with grapes

Spotted lanternflies have an apparent appetite for grapes, wine or juice, with 200 to 250 feedings per vine.

"That's a lot of pressure to put on a single vine," she says. "Vines are getting so depleted that they can get killed, or they can't produce any fruit. A lot of growers have killed vines."

Leach isn't as concerned with tree fruits, at least for now, as the lanternflies only spend one or two weeks feeding on the trees and then disperse to other crops. But the effects of those feedings is unclear right now, she says, and more research needs to be done.

A summer survey of at least 90 grape growers in the state found that most growers have doubled or even tripled their sprayings in vineyards, anywhere from four to six sprayings all the way up to 16 sprayings to deal with the pest.

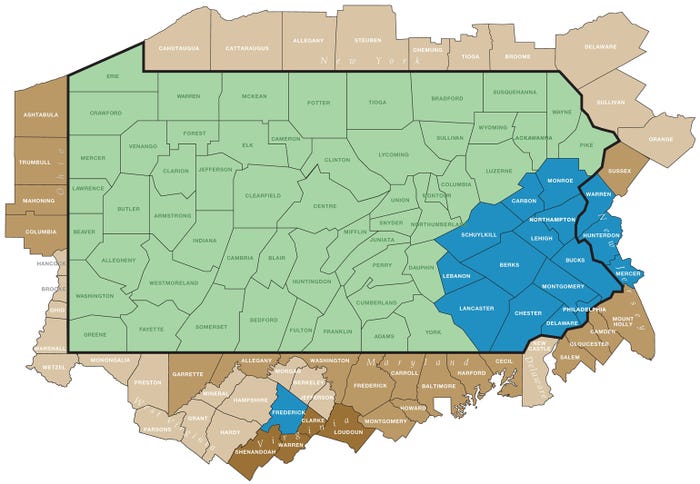

RAPID SPREAD: Spotted lanternfly has spread into most southeast Pennsylvania counties as well as to New Jersey.

RAPID SPREAD: Spotted lanternfly has spread into most southeast Pennsylvania counties as well as to New Jersey.

"We're seeing a big increase, which is obviously driving up costs," she says. "And they have to deal with the labor of getting the sprays on."

Short-term spray solutions

Even the sprays that are currently available don't offer much of a residual. A trial this summer conducted at the Peiffer Turf Farm in Berks County, Penn., showed only one product provided 50% residual control of spotted lanternfly after 14 days. You can find the data online. (https://bit.ly/2wg4sBw) There is also a list of labeled insecticides for spotted lanternfly.

The study was done on 2-year-old peach trees. It evaluated 20 different insecticides on third-stage nymphs right after application, seven days after application and two weeks after application. Nymphs were placed in cages in the orchard and were exposed for 48 hours at each testing interval.

A couple of sprays being evaluated for longer-term control were removed from the test, leaving 16 varieties to be tested. Initial control right after application was around 100% for 14 of the 16 sprays.

In the one-week test, seven products achieved at least 50% control, which was the threshold of control set by researchers. Only one product got at least 50% control in the 14-day test.

Leach says the tests are not unusual, as most insecticides offer very little residual control of most pests. Still, the fact that most growers must deal with another pest in the orchard or vineyard will only drive up costs.

EGG MASSES: Female spotted lanternflies lay two egg masses with between 100 and 120 eggs. The masses can be scraped off hard surfaces or sprayed.

EGG MASSES: Female spotted lanternflies lay two egg masses with between 100 and 120 eggs. The masses can be scraped off hard surfaces or sprayed.

There are at least five insecticides that have a label.

Hope for a predator

The long-term hope is that a bug with a taste for spotted lanternfly can be found and dispersed into the environment.

Two potential bugs are currently in quarantine at the USDA's Beneficial Insects Introduction Research Unit in Newark, Del.

Kim Hoelmer, research leader, says the parasites were brought over from China after researchers contacted Chinese officials two years ago. One of the parasites attacks egg masses while the other attacks nymphs.

Hoelmer says researchers are studying both parasites to rear more of them and see how they do in a controlled environment. Targeted insects that can be reared more easily in a lab, he says, can lead to quicker release of a predator, but the spotted lanternfly has proven difficult to breed as there is only one generation a year and it is not easy to breed in a lab.

Hoelmer says it could take several years before one of these potential predators is released.

"We want to be sure they don't attack any nontarget insects," he says.

Then again, Mother Nature might take care of dispersing the parasite herself, as what happened with the samurai wasp, a known predator of the brown marmorated stink bug.

Hoelmer says that just as the wasp was going to be released for host-range evaluations, it was discovered that the wasp was already established in the U.S., somehow hitching a ride from its native Asia.

The wasp has spread to most Northeast states along with Ohio and Michigan, and Oregon and Washington on the West Coast.

Hoelmer says it's too early to tell if the wasp is helping control the stink bug, but the hope is that Mother Nature will have provided the long-term solution researchers were looking for.

You May Also Like