February 21, 2014

By Chris Ries

Chris Ries of Ries Ag Marketing is a private market analyst in northeast Iowa. He can be reached at 563-932-2646 or [email protected].

Brazil is changing. Hundreds of billions of dollars in infrastructure investment from public and private partnerships is set to overhaul the country's grain export program over the next decade. Highways and railways will extend deeper into Brazil's agriculturally rich interior than ever before, carrying grain to ports that are expanding to meet this growing opportunity.

While many of these investments are still years from paying off, some of Brazil's farmers are already reaping the benefits from an exciting new route to the north.

IMPROVING MARKET ACCESS: Brazil's infrastructure has long been an easy target for critics, but the theme during the next 10 years may become more about what Brazil is doing right, rather than what they're doing wrong.

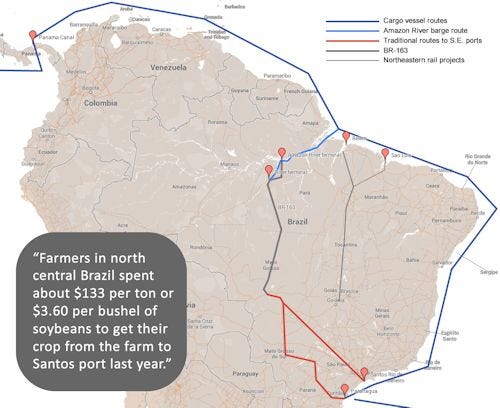

Since the Panama Canal remains a major gateway for South American agricultural exports to Asia, much of the new infrastructure investment is taking place in northern Brazil. Today, nearly all of Brazil's corn and soybean exports flow through ports in the country's southeast. The largest of these ports, Santos and Paranagua, handle nearly three quarters of Brazil's trade.

Brazil is a big country, the fifth largest in terms of area in the world. Ships carrying grain bound for Asia via Panama must go around the country's eastern shoreline which jets out into the Atlantic, adding thousands of nautical miles and resulting in a voyage to Panama that's about twice as long as routes from ports in the north.

Farmers in north-central Brazil spent about $133 per ton or $3.60 per bushel of soybeans to get their crop to the port of Santos last year.

But farmers in Brazil's interior continue to ship the vast majority of their grain southeast, instead of north, even though the overland distance is about equal either way. Why? Because Brazil's northern ports are underdeveloped, as are the highways and railways to get there. That makes transporting grain from central Brazil to northern ports too expensive for most.

The Brazilian government, farmers and exporters are keenly aware of the economic advantages northern port access brings. In little more than 10 years, corn and soybean production has doubled, but there has been relatively little investment in transportation infrastructure. Ports in the southeast are overcrowded with vessels, and trucks carrying corn and soybeans plug the nation's highways each spring.

~~~PAGE_BREAK_HERE~~~

Northern port access would mean less congestion, and less congestion means cheaper transportation costs. Farmers in north- central Brazil spent about $133 per ton or $3.60 per bushel of soybeans to get their crop from the farm to Santos port last year.

Many farmers in Brazil's largest soy producing state, Mato Grosso, have been waiting for better access to markets since moving to farm there more than 30 years ago.

Economics start to mean good politics

Until recently, the major barriers to infrastructure investment have had more to do with politics than economics. Private sector investment in Brazil has long been shunned by a government that viewed privatization as a risk to Brazilian jobs. But as economic growth has slowed in recent years, the government is beginning to look at new opportunities for growth. In 2012, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff announced the country would award $100 billion worth of infrastructure projects to various companies to operate seaports, roads, airports and railways privately for the first time.

With the political environment improving and the advantages of northern port access clear, businesses have begun to improve roads and expand ports in northern Brazil.

Better roads make northern ports viable for central Brazil's farmers

The main corridor to the north from central Brazil, BR-163, otherwise known as the "soy highway," is finally being completed. Currently, about one-third of the highway from the northern border of Mato Grosso to the nearest markets on the Amazon River, remains unpaved. These unfinished stretches of highway can be impassable during the rainy season, which lasts through April but is particularly heavy in February and March when the soy harvest is in full swing. Outside of the rainy season, unpaved roads present greater hazards for truckers, risks passed on to farmers through higher transportation costs.

Still, the portion of the highway that is paved has increased substantially in recent years and Brazil's soybean producers association, Aprosoja, says it expects a tenfold increase in the amount of grain transported over the road this year.

~~~PAGE_BREAK_HERE~~~

Completion of BR-163 is expected to lower grain transportation costs by 11% for farmers in central Brazil, after accounting for tolls charged by private highway operators, according to the Mato Grosso Institute of Ag Economics.

Getting from pavement to port

But the soy highway ends long before it meets major export terminals in the north. To finish the job, exporters are investing heavily in terminals on the Amazon River and its tributaries. Here companies like Cargill and Bunge plan to buy soybeans off the highway and load them onto barges small enough to traverse the heavily silted Amazon River. From there, barges float east to large ports near Belem in the state of Para where grain can finally be loaded onto ships for export to Asia.

About 2.5 million tons or 3% of Brazil's soybean crop will be exported this way in 2014, but Aprosoja says that will jump to 12 million tons by 2016. Transportation costs via this route will be 34% less than routes through southeastern ports.

A bit further south and east of Belem is the port of Itaqui near Sao Luis in the state of Maranhao. This promising port sits along an existing railway that connects it with the states of Para and Tocantins, minor soybean producing states. But with further investment the railway will connect Itaqui with the state of Goias, the third largest soy producing state in Brazil.

Itaqui is constructing a new grain terminal with planned export capacity of 10 million tons per year. Phase one of construction will be completed this spring with an initial capacity of 5 million tons. Phase two will expand capacity by an additional 5 million, but won't be completed until 2018.

A zoning and development plan shows the Itaqui port with 3.2 million tons of grain handling capacity this year, growing to 6.5 million in 2017 and 12.4 million by 2025.

~~~PAGE_BREAK_HERE~~~

Expanding Brazil's rail infrastructure will be critical to achieving Itaqui's potential, just as it will be for all of Brazil. A government program, launched in 2012, aims to improve or expand 6,200 miles of track through a combination of public and private investment. Eventually, a 'soy railroad' will connect central Brazilian farms with ports in the north. It's a grand plan but government concessions for building the line are still in the process of being awarded.

Brazil's largest southeastern ports are expanding too

A new port law passed last year promises to stimulate private investment, increase the grain handling capacity and reduce transportation costs by allowing private companies to operate terminals at Santos and Paranagua. New loading facilities are expected to reduce the amount of time vessels spend waiting in line for grain from months to weeks.

Private companies plan to invest $11 billion in 50 new terminals over the next few years.

Public employees fought the new port law fiercely, staging numerous national strikes last season. Even after passage, labor unions continue to threaten additional strikes this year.

Brazil is also trying to manage existing infrastructure better

In the short term, Brazil will try to more effectively manage the infrastructure that already exists. A new system of electronically staging grain trucks along highways far from port is being tested this year with hope of reducing bottlenecks at the delivery point. Another program aptly named Porto 24 Horas will allow, for the first time, ports to operate 24 hours a day. And work to install a system of covers at some of the terminals will allow grain to be loaded in the rain—especially important since the busiest months for soy exports are also some of Brazil's wettest.

This year, Brazil's soybean export program will benefit more due to a smaller corn harvest than as a result of improving export capacity. Last spring, both corn and soy exports competed with each other as the world suffered from shortages following the U.S. drought. This year, with world corn supplies replenished, Brazil will produce about 15% less corn.

Summing up: Brazil's infrastructure has long been an easy target for critics, but the theme for the remainder of the decade may become more about what Brazil is doing right, rather than what they're doing wrong.

You May Also Like