Harvest may be in full throttle but Chris Edgington is already worried about next year’s profit margins.

“The crop budgeting for next year is going to be a challenge,” says the St. Ansgar, Iowa corn and soybean farmer and outgoing president of the National Corn Growers Association.

Supply chain issues, import-export restrictions and the war in Europe has caused fertilizer prices – especially nitrogen – to remain stubbornly high going into the 2023 crop input buying season. That has farmers like Edgington thinking about alternatives.

“Farmers, if they don’t split apply N, they may want to start, because you can save a few dollars,” he says. “If nitrogen remains costly they may put a few more beans out next spring. Some may look to a neighbor for manure -- It doesn’t happen much, but it could.”

High stakes

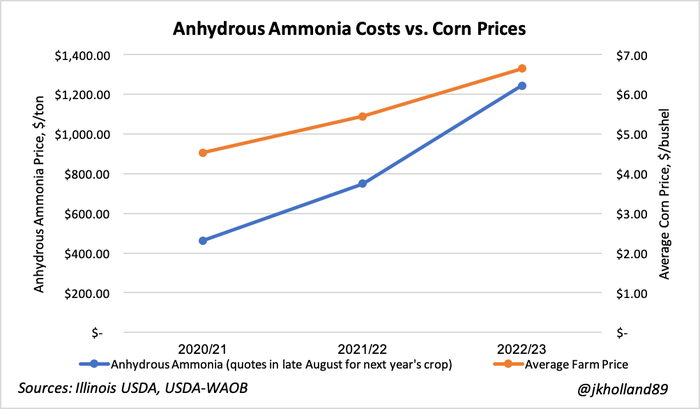

After a couple years of healthy profits, 2023 is already feeling like a high-stakes game of poker. U.S. crop input costs jumped 14% year over year and Brazil is gearing up to put in a big crop, which could take the air out of a long-running bull market. Meanwhile China cut fertilizer exports; Europe, the world’s third largest anhydrous producer, shuttered anhydrous plants when Russia turned off its natural gas.

All that supply tightening means nitrogen costs will likely remain at or close to record highs for the short term. Fertilizer accounts for over a third of a corn farmer's operating costs.

Yet, simply cutting N rates without making other changes could harm yields.

“A lot of people are going to ask, do I simply cut back?” says Edgington, who split applies liquid 28% N at planting and side dress. “At today’s prices if you cut 15 to 20 pounds of N per acre out of your program that’s real savings – but you have to determine if you’re going to risk the equivalent in yield.

“In some situations with certain soils you won’t be hurt, but if you have some cool summers you could lose yield,” he continues. “A combination of heat and moisture allows soil to mineralize nitrogen for the plant. It’s hard to bank on that, especially if you’re applying far in advance of when you need it.”

A better approach may be to find your economic optimum nitrogen rate and target maximum economic yields, an approach Tom McKinney has embraced. He applies nitrogen in two and possibly three in-season split applications, starting with 2X2 starter at planting.

“We strategically place nitrogen next to the seed, spoon feeding 28% UAN (Urea Ammonium Nitrate) with the planter, along with Ammonium Thiosulfate,” says the Kempton, IN farmer. “Then we sidedress with anhydrous when corn is at V4 or V5 because it’s the most cost effective.”

Cost effective nitrogen

McKinney believes the in-season approach is better for the environment – as well as his wallet.

“It all has to boil down to cost effectiveness,” he says.

Experts who have been studying nitrogen management in high yield corn believe farmers like Edgington and McKinney are on to something.

“We’re starting to see a fair number of people go to planter applied nitrogen, then sidedress,” says University of Illinois crop scientist Fred Below. “If there’s a weather issue after the corn is up you can sidedress with a high boy at growth stage V9.

“Applying a third of your N at planting on both sides of the row is a great approach, because that makes the plant set its yield trajectory. Then you come back later and side dress.”

Jim Schwartz, Beck’s director of research, agronomy, and the company’s Practical Farm Research program, says a farm’s best nitrogen spend is driven by rate, placement, timing, and source. Citing four-year multisite research data from Beck’s, 30 units UAN applied 2 by 2 and 160 units UAN sidedress at V3 showed an average increase of $72.36 per acre over the control of 190 units UAN preplant. At 95 units preplant plus 95 units sidedress at V4, corn averaged a $55.88-per-acre increase over the control.

McKinney is hoping to take this approach to another level. He is looking at the possibility of using AgMRI, which provides air and satellite crop images, to tell if certain corn fields are short on N by mid-season, and if so, side dress again using Y drops at growth stage V9.

“We’re not doing it yet, but if the cost of nitrogen stays up, we will,” he adds. “It is worth the $5 cost per acre, and we can use our own high-clearance sprayer.”

Growers who plant a lot of corn acres often shun side dressing due to weather risk. Plus, it’s another field pass, which costs money. But new short-stature corn hybrids are about to hit the market, making crop size less consequential to in-season applications. If nitrogen costs continue higher, you can increase fertilizer efficiency by applying N closer to the time it needs it. You also avoid potential losses from extreme rainfall events, which have grown in frequency the past 20 years.

“Putting nitrogen on in the fall seven months before the plant uses it is for convenience only,” says Below. “You get a task done, but then you’re at the mercy of the weather.”

Modern hybrids use more nitrogen later in the season. According to McKinney 85% of corn’s nitrogen uptake is after tasseling, or grain fill – so why put it on the fall before?

“If you have an N stabilizer for fall-applied that’s great, but if you have a flood it’s washed away,” he adds.

4Rs

High costs have farmers re-calculating not just how much N they need, but also how to apply it best to achieve top yields. At the very least you want to brush up on the 4Rs – right source, right rate, right time, right place. Ag retailers can help tighten your spend, especially if you use variable rate technology.

A few decades ago land grant Universities recommended applying 1.2 lb. N per expected bu. yield. Today that’s down to 1.0, says Below, because the concentration of protein in grain has gone down as yields grew larger.

“The old line of thinking was that corn had 10% protein but it’s now more like 8%, and since 70% of N ends up in grain and the protein is lower, then the requirement for nitrogen is lower,” he explains.

McKinney applies about .95 lbs. N per forecasted bu. per acre. “As our yields increase due to pattern tiling, we still do stalk nitrate testing to make sure we have just a little nitrogen left by the end of the growing season,” he adds. “We apply 195 lbs. actual N per corn acre where we know we have good tile, feeding the black ground and trimming it back in some high ground. But as we keep tiling and holding that nitrogen in place, we don’t want to short that crop.”

Nationwide, farmers apply 160 lbs. N per acre on average, with higher rates going on more productive fields, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service.

Even so, farmers often apply ‘insurance nitrogen’ – more nitrogen than a given field can possibly return in higher yield.

“The economic cost of under-applying N is greater than the economic cost of over applying, even with $1,500 per ton anhydrous,” Below says. “Even so, my guess is, a little less insurance N went on in 2022 because of the price.”

Another twist making nitrogen rates more difficult to nail down is that about half the N the plant takes up is mineralized from the soil.

“That means it’s hard to say exactly how much N you need because in some years the soils provide more,” says Below. Schwartz agrees, noting that in 2021, conditions such as oxygen, moisture, good temperatures, and balanced pH all favored soil N mineralization.

“It’s important to understand this,” he says. “Applied nitrogen has very little correlation to final yield. We might not need that much N.”

This is what makes telling a farmer how much they need to apply a non-exact science, Below points out. “We know the crop needs about a pound per expected bushel yield, but weather and soil cause uncertainty.”

All of which has farmers looking more closely than ever at next year’s crop budgets.

“Before inflation and Ukraine, we could make a profit at $3.80 per bu.; now our breakeven is at $4.60 per bu.,” concludes McKinney. “Now we need the extra cash from the market to pay for next year’s crop inputs.

“We’ll have to take some risk. We don’t know where crop prices or input costs are going.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like