August 28, 2018

Like other livestock farmers trying to make a living in the grasp of a severe drought, Adam Boman was on the road to Kansas City, Mo., in early August to market some of his cattle. But Boman, owner of Good Life Grass Farms, was only transporting the few cows he direct-markets each month. The others were still back on the Lawrence County farm where he raises grass-fed beef in a rotational-grazing system that was still providing plenty of forage for his herd.

“Even through this summer, I shouldn’t have to feed any hay,” the Pierce City, Mo., farmer says. “There is still plenty of fescue in the fields. It is still green, but has stopped growing for sure. But thus far we are getting enough rain here and there to where the warm-season grasses are continuing to grow.”

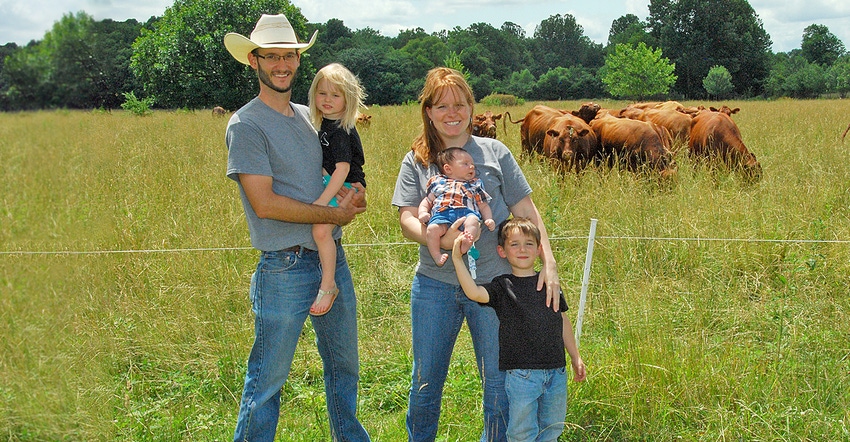

Boman says the combination of rotational grazing and direct marketing is profitable and allows him time to care for his three young children when his wife, Teresa, is working. Teresa is an associate professor at Missouri Southern State University.

Farm system design

Boman, who also raises and direct markets grass-fed lambs, says the grazing system allows him to rotate 22 cattle through 13 permanent paddocks that can be turned into 26 with temporary fencing. The system allows him to manage the grass resource so that it does not get overgrazed and it builds in plenty of rest periods for the grass to recover.

Boman says the grazing system has allowed him to make three important management changes: evenly grazing half of the growth and leaving the other half; increasing days of rest between grazing; and keeping the animals only eating the high-energy grass tips during fast-growing periods in early fall and early spring.

He says these practices resulted creating more drought resilience, in part because accumulated grass cover from spring keeps soil temperatures lower and helps retain soil moisture in the summer. He also found the managed grazing allowed him to grow more forage per acre while maintaining stock rates and to feed less hay.

PLENTY OF GREEN: Red Angus cattle at the Boman farm graze in a paddock of grass during the summer of 2018. It was an unusual sight for many beef producers during the drought.

PLENTY OF GREEN: Red Angus cattle at the Boman farm graze in a paddock of grass during the summer of 2018. It was an unusual sight for many beef producers during the drought.

“My stocking rate is 1.9 acres per animal unit. That is close to the typical stocking rate in my area. But the impressive part is how long we can graze without feeding hay,” Boman says. “By leaving grass behind you throughout the year, once winter hits you end up with a large amount of stockpiled grass that can be strip-grazed once grass stops growing.”

Grazing power

Last year, cattle grazed through the dry spell in the fall all the way to Jan. 5, which Boman says cut down on hay usage, ultimately making the farm more profitable.

Boman says because last fall was dry, followed by a cold, wet spring, most of the livestock farmers in the area had to feed hay from early November until the end of April. On the other hand, he was grazing his herd again on March 7.

“We were feeding hay for two months vs. six months,” he says. “That’s because healthier plants begin growing back a lot sooner. The key is to leave plenty of grass height throughout the growing season, to not brush hog or mow grass into the ground any time of the year, and to leave 4 to 6 inches of grass residual in the winter when you start feeding hay. Let the cows clean up the field when they start grazing in March. They will really go after that dead grass left from last year because they crave the fiber in March.”

Boman says he can’t imagine operating without his rotational-grazing system.

“People say, ‘But you have to move them every day,’ but it only takes five minutes,” he says.

Boman, who grew up on a farm in the area, says he wondered when he was young if he could ever make a living at farming. He is learning that he can.

“The key is regenerative agriculture and direct marketing,” he says. “I learned that by direct marketing and not owning a lot of equipment, you can make a living off of agriculture.”

Rahm is the public affairs officer for the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. He writes from Columbia, Mo.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like