February 13, 2020

You can’t judge how molds have affected the quality livestock feed by the color of the mold, according to Michelle Mostrom, North Dakota State veterinary toxicologist.

Certain molds such as Aspergillus spp. and Penicillium spp. are green, Alternaria spp. and Cladosporium spp. are black, and Fusarium spp., Diploidia spp. and some Penicillium spp. can be white.

But mold growth does not always mean that toxins were produced. Also, molds can grow and die, and not be visually detected, yet they may have produced toxins that are in the feed.

If molds are present in livestock feeds, the best approach is to discard the moldy portions of the feed and feed that appears to be normal. This may not completely avoid problems because, while the mold may be gone, the mycotoxins remain in the feedstuff, Mostrom says.

“As a veterinary toxicologist, I would say to be proactive and test a feedstuff that appears to be moldy for mycotoxins before feeding to animals, particularly pregnant animals,” Mostrom says.

“Try to collect a representative sample of the feed,” she adds. “The best is to collect multiple samples of grain while transporting the feed from the field to bins or to a truck, or collect multiple samples of hay (e.g., probe) or silage during feeding.”

If the feed is positive for mycotoxins, certain animals may not be affected by that particular contamination level or may be capable of metabolizing the mycotoxin. Under some situations, the mycotoxin feed can be diluted to a safe level in the final ration.

“The exception is aflatoxin-contaminated feed, which is potentially carcinogenic,” says Yuri Montanholi, NDSU Extension beef cattle specialist.

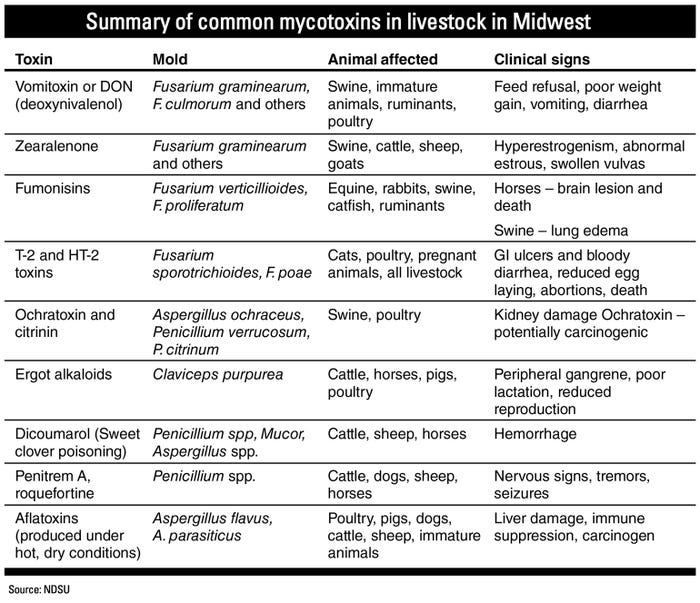

Different mold toxins can cause a variety of clinical signs in different species. An initial clinical sign of toxic feed can be feed refusal, poor weight gain and diarrhea. With continual mycotoxin exposure or exposure to high doses of toxins, damage can occur to the animal’s liver, kidneys, brain, fetus and other organs.

You cannot test for all mycotoxins and call a feed “safe,” Mostrom says.

“Scientists have discovered that these molds can produce hundreds to thousands of mycotoxins, and we do not know how all of the toxins affect animals and do not have standards or tests for all toxins,” she says. “Laboratories can test for the more common mycotoxins that are known to cause harm in animals and provide some guidance for feeding contaminated feeds. This is certainly a good start to minimize problems with mycotoxins.”

Contact your county’s Extension agent or an NDSU Extension specialist to learn more about sampling for mycotoxin analysis, as well as for other feed analysis related to quality.

Many countries, including the U.S., have regulatory limits or advisory guidelines on contamination of mycotoxins in human and animal feeds. These mycotoxin limits in food and feed can vary significantly with susceptible species, age of the animal and production status. The mycotoxin guidelines are available on the Food and Drug Administration website, or contact your local veterinarian or the NDSU Veterinary Diagnostic Lab.

Source: NDSU, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

Read more about:

MoldYou May Also Like