January 10, 2017

Think Different

Bioreactors and saturated buffers have been getting attention as edge-of-field practices that remove nitrates from water before it leaves crop fields for Iowa streams. However, strategically placed, restored wetlands may be the practice that puts farmers over the top to meet the state’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy goals.

--------------

It’s been four years since Tim Minton restored a 6-acre wetland along a stream. “I’d had a fair amount of trouble farming that area consistently because that stream had flooded my crops and made the land tough to farm,” the Dallas County, Iowa farmer says. “The Iowa Department of Agriculture approached me with a proposal to restore a wetland with CREP funding,” Minton says. “The flooding and sediment were what I was concerned with, but the concept of removing nitrate from the water in the stream over the long term with a permanent practice makes sense to me, too. I can see the water is clear coming out of that wetland. The wetland is doing the job they said it would do.”

In fact, Minton liked the way his first wetland turned out so much that he asked the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship (IDALS) if they would be interested in restoring a second wetland on another piece of land he had just purchased. “It seemed to me the same benefits would apply to that farm, too—the areas were similar, except the second would drain 2,500 acres, twice as much land as the first, and would have more than twice the pool area.”

Costs covered by CREP

Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program helped Minton restore his two wetlands. It’s an offshoot of the Conservation Reserve Program, and is being used to reduce nitrate loads in streams across 37 counties in central and north-central Iowa.

CREP wetland on Tim Minton farm, Dallas County, Iowa.

(CREP wetlands like this one on Tim Minton’s farm are larger, strategically placed wetlands being restored in the tile-drained region of North Central Iowa. On average, they can remove from 30 to 70 percent of nitrate from tile drainage water.)

Like CRP, CREP wetlands offer land rental payments for 15 years. With the state of Iowa as a partner, the program also offers an incentive payment for a long-term easement on the wetland and surrounding buffer, and cost reimbursement for constructing the wetland.

“They pay more for a permanent easement,” Minton says. “You’re giving up farm income for the life of the property. But in my case it’s made the rest of the field easier to farm. The payments are fair, and the people were good to work with.”

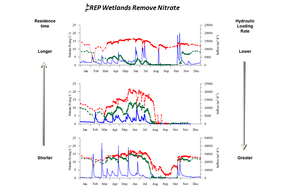

(ISU monitoring of CREP wetlands confirms that they work throughout the year, and that longer residence times and lower hydraulic loading rates result in more nitrate removal. The red line represents nitrate concentrations of water entering wetlands; the green line is nitrate leaving the wetland. The blue line represents the rate of flow.)

(ISU monitoring of CREP wetlands confirms that they work throughout the year, and that longer residence times and lower hydraulic loading rates result in more nitrate removal. The red line represents nitrate concentrations of water entering wetlands; the green line is nitrate leaving the wetland. The blue line represents the rate of flow.)

Minton says he likes seeing wildlife in the surrounding prairie buffer, and apparently other people do, too. His land is only a few miles from the Des Moines metro area. “It’s surprised me to see how many people notice it—bird watchers are out on the road with their binoculars and cameras a lot.”

CREP wetland on Tim Minton farm, Dallas County, Iowa.

Wetlands remove 30-70% of tile water nitrates

Many years of research and 15 years of CREP wetland monitoring by Iowa State University confirm properly sized and placed wetlands are one of the most effective nitrate removal practices in Iowa’s tile-drained landscapes. While removal rates vary depending on weather conditions, monitoring shows that on average, CREP wetlands can remove 30-70 percent of nitrate from tile water entering the wetland.

CREP wetlands are selected and designed for effective nitrate removal and must intercept flow from tile-drained catchments of at least 500 acres. Larger wetlands can remove a higher percentage of nitrate—to insure adequate nitrate removal, CREP requires wetland pools to be between 0.5 and 2 percent of the upper lying drainage area.

“CREP wetlands have proven effective across the wide range of conditions found in Iowa, removing nitrate under widely varying weather conditions across seasons and years,” says Iowa State University professor Bill Crumpton. “If we’re going to meet the state goal of 45 percent nitrate reduction in Iowa’s streams and rivers, CREP-style wetlands are going to have to be part of the mix.”

Because funding is limited, there’s a five-year wait right now for CREP funds for the people who have interest and eligible land.

“These wetlands are workhorses for nitrate removal,” says Matt Lechtenberg, who coordinated CREP for IDALS for seven years. Now he’s overseeing the Iowa Water Quality Initiative, established in 2013 to help implement Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy. “We know they work. There’s potential for thousands of them to help provide the long term nitrate reductions we need.”

Rebuild aging tile mains

Four of Iowa’s 83 CREP wetlands and one mitigation wetland are part of a pilot study looking at coupling strategically-located wetlands with updates of tile mains in north-central Iowa, where drainage district systems are beginning to fail due to aging.

Iowa’s 3,000 drainage districts have the opportunity to rebuild their aging infrastructure in a way that’s a win for both agriculture and the environment. As drainage districts rebuild these systems to more modern standards, crop production will improve while decreasing surface runoff.

When main systems are updated without considering wetlands at the outset, outlet elevations may be too low to include nitrate-removing wetlands after the fact. If CREP-type wetlands are included as part of the design for tile main updates, nitrate can be removed at the same time, with multiple benefits.

Fees paid by farmers on the sale of ag fertilizer and chemicals and a $1 million technology development grant from the EPA are funding the study, called the Iowa Wetland Landscape Systems Initiative. “This aging infrastructure will eventually need to be replaced and these pilot projects are showing a way to couple improved crop production with wetlands to improve water quality at a significant scale,” Lechtenberg says. “It’s seldom these market driven approaches come along and now is the time to demonstrate this linkage. An added benefit is this approach has the potential to reduce the dependence on state and federal funding for implementation of wetlands.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like