In Irrigation Extra, we’ve been following the idea of investing in drip irrigation for row crops. Technology once thought to value only specialty crops like strawberries and fruit trees can actually boost the bottom line for your corn or soybean field. Yet there are skeptics out there, even though work at institutions including Kansas State University shows the drip lines can be installed and remain in place for years.

Kurt Grimm, who works with NutraDrip, a major installer of these systems, has been behind a program to put some data behind the marketing. Working with farmers in a diverse area, he’s showing some astounding yield benefits in part due not only to water delivery, but also through modeling and providing key nutrients as the plant needs it. But what does that mean to a farmer?

How does Grimm define the work he’s doing? “What if I told you you could buy land for $2,000 per acre out the back door and have it paid off in less than seven years?” he says. “That’s the mantra; you’re taking land you already have and adding value to it with this technology. And that’s better than spending $7,000 or $8,000 an acre. And you can take your worst land and make it better than your best.”

Bold promises, but using a combination of drip irrigation and nutrient modeling for accurate delivery to the crop, he’s seeing results. For 2017, the research work added more farms, but Grimm also says the work turned up the intensity on water management. The key is not to overwater, which “is what we learned a lot of guys are doing,” he says.

He adds that this idea speaks across all forms of irrigation. Farmers tend to overwater. “If you took a sensor and put it in a guy’s field without telling him, you’d learn he’s over watering nine times out of 10,” Grimm said.

Overwatering does two major things. First, it drives nutrients deeper into the soil profile, often away from plant roots. And second, it lowers the amount of air in the soil, which isn’t good for plant roots. “Keeping the perfect moisture content is so, so important,” Grimm says.

EQUIPMENT NEEDED: Installing a drip system involves added hardware and an upfront investment, but the returns are being demonstrated in year-over-year trials. (Photo courtesy of NutraDrip)

For his 2017 work, in an effort to deliver just the right amount of water to plants with drip systems, Grimm used three tools. The first is soil moisture probes, which measured water in the soil profile.

The second is a plant temperature sensor that can measure plant temperature every 15 minutes, to know when the plant is getting outside the optimum temperature zone. “If we see a plant ‘overheating’ we can turn on the drip system and watch the plant temperature decline,” he says.

That precise water delivery through the system — and a drip setup provides whole-feel water as needed — can also help reduce plant stress.

The final sensor is a new tool that measures the shrink and swelling in the stalk of the plant. “You want to see a little shrink during the day,” Grimm says. “If you don’t see that shrink, the plant is too wet.”

Using these measurements to maximize sensors, the drip trials aimed to optimize whole-field performance.

Maximizing nutrients

Grimm innovated nutrient delivery by getting a better handle on just when the crop wants to be fed. There’s plenty of plant physiology research available that provides that information, which he’s used to optimize his nutrient program. But for 2017, he went further.

“We’re doing sap analysis this year[2017]; we brought that in the mix because tissue sampling can be unpredictable,” he says. “The tissue sample can provide information about percent of nutrients in a plant, but sampling plants of different size in the field can be inaccurate for nutrient use.”

With sap analysis, Grimm says he started looking at balance in the plant. With the tissue samples, Grimm looks at the ratios of nitrogen to phosphorus, nitrogen to potassium, and nitrogen to sulfur. This level of analysis provides added detail for decision-making when applying nutrients.

And what did he learn in 2017? “In our tissue samples (along with sap analysis) we learned that the difference between a 300-bushel crop and a higher-yielding crop was greater levels of all nutrients available to the plant early in the season,” he says.

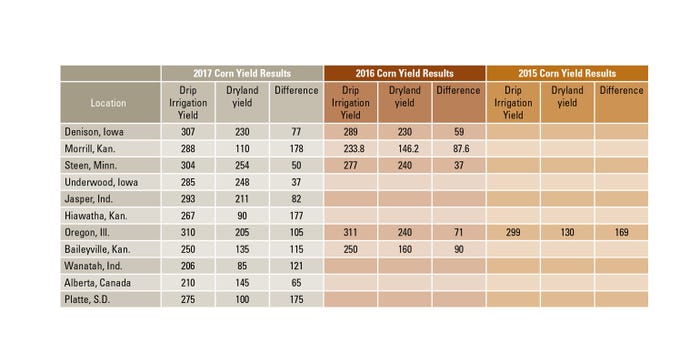

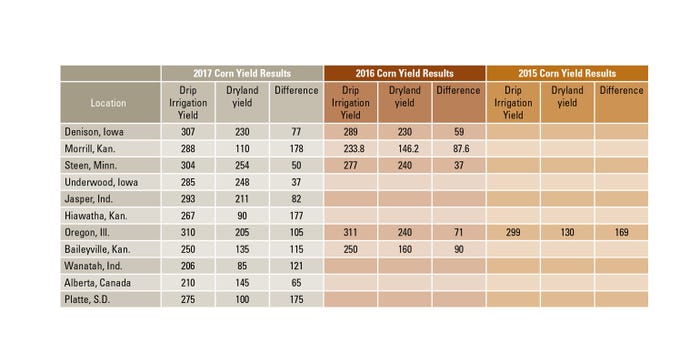

This table of yields looks at some multiyear data for corn, where all the results are positive. (Source: NutraDrip trials)

What he’s found is that the difference between a potential 300-bushel crop an even higher-yielding crop, learned from contest entries, is that while the 300-bushel potential has about 4% to 5% nitrogen at V3, the higher yielding crop is above 6%. “They are somehow at extremely high levels,” he says.

That doesn’t mean there’s a benefit to fall N directly, but it does call for ways to deliver higher concentrations of nitrogen to those early plants. “We’re not saying you need a lot of nitrogen early, but it needs to be a high concentration for the plant,” he says.

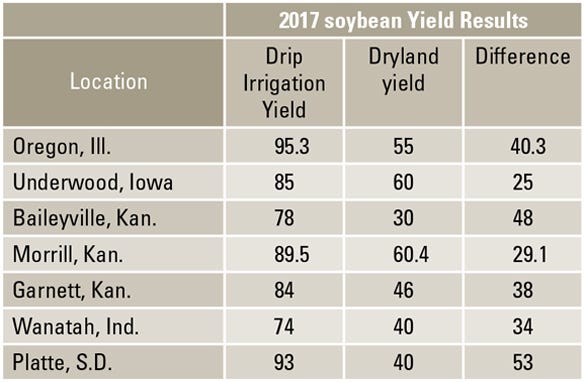

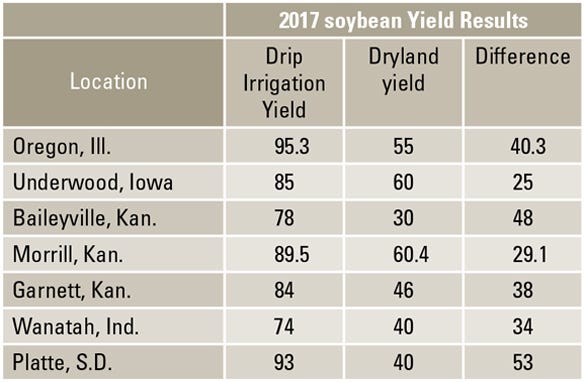

This table of yields looks at some multiyear data for soybeans, where all the results are positive. (Source: NutraDrip trials)

It’s work like this that Grimm says will continue as his firm, NutraDrip, aims for higher yields through better delivery of nutrients to the crop in the growing season. Drip irrigation offers that potential; and even with the high upfront cost for installation, the data show that there is a payoff in higher potential returns for row crop country.

The table with this report shows information for corn and soybeans. It’s the first year for drip irrigation for soybeans in the trials, but the numbers show a boost in yields. For corn, there are some second- and third-year numbers that show consistency over time.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like