In the wake of retaliatory tariffs targeted at U.S. agricultural goods, USDA paid out a total of $23 billion to farmers under the 2019 and 2019 Market Facilitation Program. In further evaluating the program, a Government Accountability Office report reveals that USDA picked winners and losers in how it allocated trade damage payments to farmers.

GAO estimated that, for example, total 2019 MFP payments to corn producers were approximately $3 billion more than USDA’s estimate of trade damage to corn, while payments to soybeans, sorghum and cotton producers were lower than their estimated trade damages.

Payments by USDA significantly overestimated the actual trade damages suffered by producers of eligible commodities, and that the calculation method USDA used in 2019 for payments to non-specialty crop producers resulted in higher payments for Southern farmers than producers of the same crop in other parts of the country.

In its estimation of the effect of foreign actions on farm producers (i.e., trade damages), USDA addressed several key elements of an economic analysis. For example, USDA assessed the sensitivity of its analysis to alternative assumptions. However, for the 2019 MFP, USDA used baselines that did not best represent what trade would be absent the retaliatory tariffs, and that increased trade damage estimates, GAO explains.

For the 2018 MFP, USDA used a justifiable baseline, the value of retaliating country imports from the U.S. of an eligible commodity in 2017, the year before retaliatory tariffs. For example, USDA estimated that China imports of U.S. wheat would decline by 61% due to retaliatory tariffs and applied that decline to the $391 million value of 2017 trade, producing a trade damage estimate of $238 million.

For the 2019 MFP, USDA policymakers requested baseline options from the Office of the Chief Economist and chose to base trade damages on a baseline OCE calculated as a sum of the highest retaliating country imports in any year from 2009-2018 of each product defining the commodity. As a result, USDA used unrepresentative baselines equal to or higher than the highest value of retaliating country imports in any one year, GAO report.

For example, in 2013, China imports of U.S. durum wheat were $182 million and of “other wheat” were at their highest ($1.1 billion)—a total of $1.3 billion. In 2017, China imports of U.S. “other wheat” were lower but durum wheat was at its highest, $289 million. USDA’s 2019 MFP wheat baseline summed the two separate highest values and exceeded $1.3 billion. USDA used the new baseline and the same estimated 61% decline to calculate 2019 MFP wheat trade damage of $836 million—more than three times the 2018 MFP estimate and more than twice the 2017 value of China imports of U.S. wheat.

For 14 of the 29 MFP-eligible commodities USDA analyzed, USDA’s 2019 MFP baseline was higher than the highest value of retaliating country imports from the U.S. in any one year from 2009 through 2018, GAO says. USDA officials explain USDA’s baseline methodology treated commodities equitably and was responsive to concerns expressed about the 2018 MFP baseline by attempting to account for policy factors such as nontariff barriers that may have been in place at different points, making it difficult to identify a single baseline.

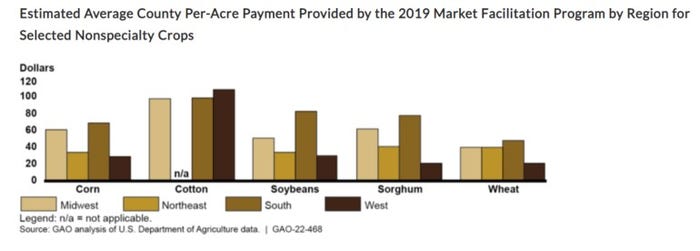

USDA’s county-based payment methodology for the 2019 MFP resulted in different payment rates for producers of the same non-specialty crop in different counties. For the 2019 MFP, a county’s crop mix (i.e., what others in the county planted) affected the payment rate. USDA paid higher rates to producers of a crop in a county where others planted crops with higher trade damages per acre than it paid producers of that same crop where others planted crops with lower trade damages per acre.

GAO says crop payment rates were generally higher in the South because of the South’s higher proportion of cotton, sorghum and soybeans, which had higher trade damages per acre. For example, though corn yields are higher in the Midwest and West, corn producers received an estimated average of $69 per acre in the South, $61 in the Midwest, $34 in the Northeast, and $29 in the West. USDA used minimum and maximum county rates to help address potential inequities, but regional differences remained.

U.S. Senator Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., chairwoman of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, was critical of the trade aid when the Trump administration released the details.

“This report confirms that the Trump USDA picked winners and losers in their trade aid programs and left everyone else behind,” Stabenow says. “Making larger payments to farmers in the South than farmers in the Midwest or elsewhere, regardless of whether those farmers actually experienced a larger loss, undermines our future ability to support farmers when real disasters occur.”

Jacqui Fatka, long-time policy editor at Farm Futures, will bring her valuable agricultural policy insight to the stage of the Business Summit in Iowa City, IA Jan. 20-21, 2021. Featuring industry experts and in-depth training sessions, it’s an opportunity to gain clear insights for a profitable future. Use code BOGO22 to receive discounted rate for a guest. Learn more and register now!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like