Ted Matthews wishes he could say, “These are the signs of people who are going to commit suicide.” Then you could check symptoms, check boxes, and take action.

“But it’s not that simple,” says Matthews, director of rural mental health for the state of Minnesota and counselor to hundreds of farmers and farm families.

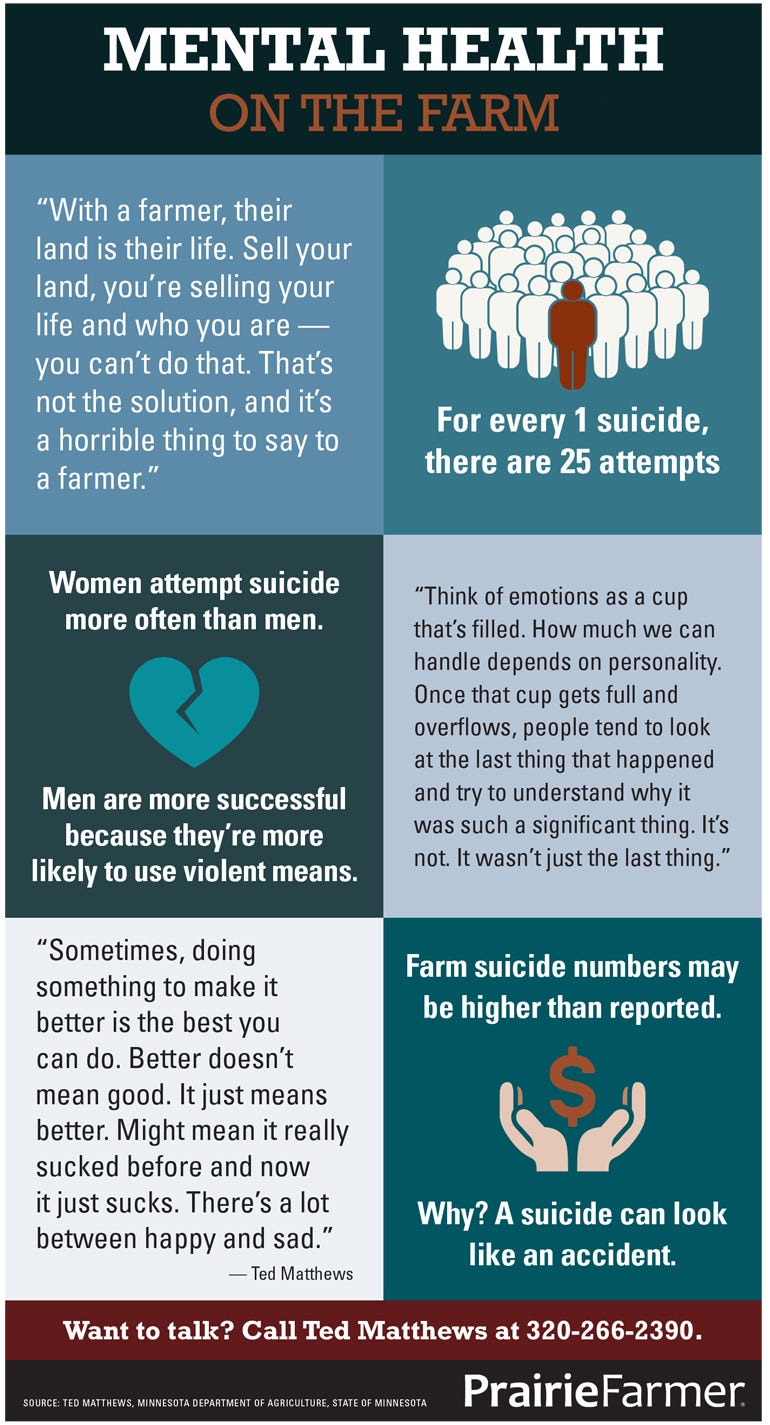

Like symptoms, data on farmer suicides are equally hard to come by. A 2016 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was retracted in June 2018 due to coding errors that suggested male farmers took their lives at a rate two times higher than the general population in 2012, and 1.5 times higher in 2015.

The errors muddied the waters, making it unclear just how many farmer suicides there are relative to the general population, in part because the study was limited to 17 states that only represent 25% of the farming population. Even with correct coding and reporting, the data is imperfect.

Matthews suspects the farmer suicide rate is higher than anything the CDC reports because what looks like an accident may actually be a suicide.

The tough part is that when someone reaches the point of suicidal ideation — where they feel the world is better off without them and imagine ways to die — a lot of thoughts seem entirely logical to them. They may think if they die, the farm will get paid off and maybe their spouse will be in a better situation.

“We can convince ourselves of all kinds of things when we decide the world is better without us,” Matthews says.

Of course, none of those ideas is true. Suicide ravages a family, leaves a spouse to deal with all the same problems as before — only now without help — and leaves wide swaths of people who feel responsible for the death.

“When I talk to people who have attempted or contemplated suicide, I talk to them about how when they lose their life, a lot of other people lose a major piece of their lives, too,” says Matthews. “No one wants to see them die. That sounds so simple, but it’s not simple to them.”

He believes that for every suicide, there are 25 attempts — none of which makes the newspaper. Women attempt suicide far more often than men, he says, adding that men are far more successful. Why? They’re more likely to use violent means, like guns.

Breaking point

Of those 25 attempts, what brings people to that point? Matthews says in trying to understand, others often look at the last thing that happened. But that’s not how it works.

“Think of emotions as a cup that’s filled,” he describes. “We don’t know how much we can handle. As that cup fills, how much you can and can’t handle depends on your personality.

“Once that cup gets full and overflows, people tend to look at the last thing that happened and try to understand why it was such a significant thing. It’s not.”

How can you know how full someone’s cup really is? It takes communication, which farmers historically aren’t great at. (They’ll talk about each other, Matthews says — just not usually about their own problems.) But he’s found farmers will talk, if you can get them on the phone. His number, 320-266-2390, rings more frequently these days because there are few resources armed with people who understand farming. And often, it’s someone else close to the farmer who reaches out to Matthews, and then prompts the farmer to talk to him.

How can you help? “When we don’t know what to do, we do nothing,” Matthews says. “But doing something beats the heck out of doing nothing.”

Seek help, he says. Suggest they “talk to Ted,” just like they’d get help fixing a tractor if they didn’t know what was wrong with it.

In some cases, knowing someone cares is enough to help.

“When people say, ‘I care about you,’ it make us feel good, doesn’t it? Sometimes that’s all I can do. I can’t fix it. I can’t change it. But I can make sure they know they have at least one person in their corner,” Matthews says. “Don’t assume ‘fixing’ means doing anything more than being nice.”

His goal at the end of the day — or a call — is to get someone to understand that doing something to make it better may be the best you can do. “Better doesn’t mean good. It just means better. It might mean it really sucked before and now it just sucks.”

Need to talk? Call Ted Matthews at 320-266-2390, and visit farmcounseling.org.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like