Editor’s note: This is the final article in a four-day series on farm succession planning that offers the last stop on the five-point road map to help you and your family walk through the process.

The idea of transitioning the farm business to the next generation is something the entire world is dealing with, says Wesley Tucker, University of Missouri Extension field specialist in agricultural business.

“This is not just the United States thing; this is not just the Midwest thing,” he explains. “Our population, our world population, is aging.”

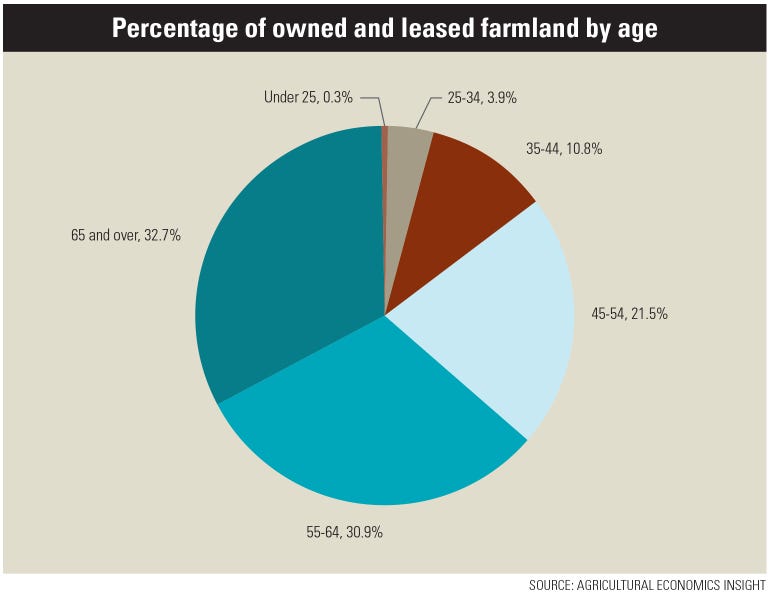

Tucker says about two-thirds of the land is controlled or owned by someone older than age 55. “The reality is probably in the next 15 years, about 70% of our land is going to change hands,” he adds.

Related: Introduction to succession planning

Along the road map to farm succession, the path to management now advances closer to majority ownership. However, like many road maps, there often are detours.

Fixing the finance glitch

Tucker says senior farmers often turn over production duties to the next generation but not finances. “Are we really building capacity in our successor if the only decisions they're allowed to make is when we rotate the cattle between pastures, or when's the time to harvest the beans?” he says. “They need to be managing the finances as well.” And this is where most succession plans fail.

Related: Part 1: Send kids off the farm for experience

It goes back to the fear of losing control, Tucker says. “If you look at research studies from multiple countries, the thing that is consistently not turned over from the senior to the junior operator is the finances,” he adds.

Once this aspect happens, the final phase of farm transition begins — becoming majority manager and owner.

Stepping back

In this phase, the senior farmer scales back, and the young farmer assumes the reins. Tucker disagrees with Iowa State University, which calls this phase “complete withdrawal.”

“I don't think it has to be complete withdrawal,” he explains. “I think that's what scares the senior generation.”

He says some farmers may want to retire, but others may not. “You don't have to get completely out of the business, but what you do have to do is turn the major management over to the next generation," Tucker says.

Related: Part 2: Setting up plan for successor to work on the farm

With so many years of experience, the senior farmer transitions to a role of adviser. Tucker likens it to moving from being the farm CEO over to the board chair. “You are still active,” he notes, “but in an advisory role.”

Ultimately, when the family navigates the road map to farm succession and does it well, the steps feel seamless. But Tucker says it takes sitting down and creating a plan. “Then it easily flows from one step to the next.”

For more on farm succession planning, contact Tucker at 417-326-4916 or [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like