July 30, 2013

Michael Kelsey intends to put his brand on the issues challenging Oklahoma cattlemen. Drought affects cattlemen today just as it did when their great grandpas moved cattle by horseback from one range to another. Government regulations also come with headaches.

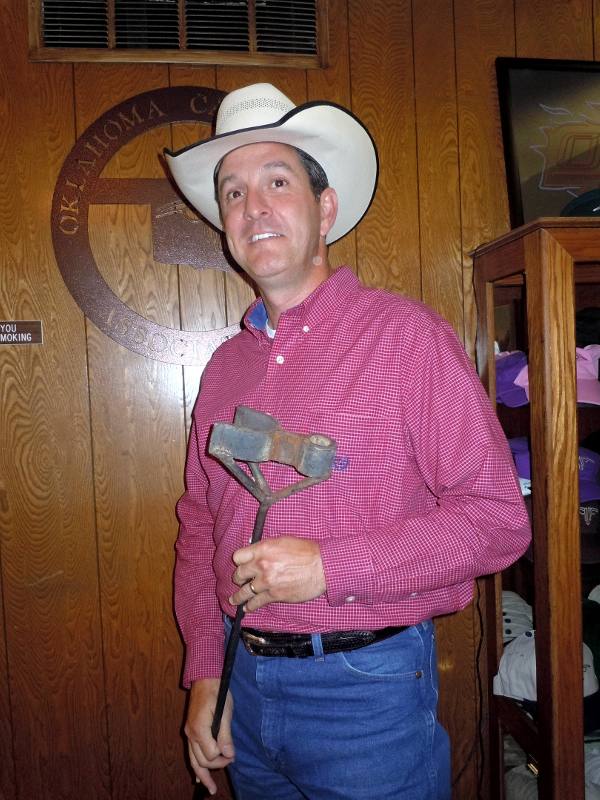

Kelsey, now in his second week on the job as the new executive vice president of the Oklahoma Cattlemen's Association in Oklahoma City, knows he and his organization have some tough problems to solve.

From government they face is the mandatory country-of-origin labeling rule (COOL) finalized by the USDA in May of this year. Eight organizations representing U.S. and Canadian meat and livestock industries have filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to stop the new rule. The lawsuit claims the COOL rule is unconstitutional, goes beyond the bounds of original law and is arbitrary and capricious.

"As cattlemen we take great pride in our cattle and the meat products obtained from them," Kelsey said. "We believe beef products produced here are nutritious and safe for consumers to eat.

"We do a good job and we don't need the government to be telling us how to do our job.”

If you are enjoying reading this article, please check out Southwest Farm Press Daily and receive the latest news right to your inbox.

The lawsuit, Kelsey said, states COOL, in its final state, violates the U.S. Constitution by compelling speech in the form of costly and detailed labels on meat products that do not directly advance a government interest. Under the Constitution, commercial speech may be compelled only where it serves a substantial government interest such as when compelled speech is aimed at preventing the spread of a contagious disease. Because these labels offer no food safety or public health benefit, yet impose costs the government estimates at $192 million, the government cannot require them, the lawsuit asserts.

COOL goes too far

Members of these organizations argue the COOL rule violates the Agriculture Marketing Act because it exceeds the authority granted to USDA in the 2008 farm bill. While Congress mandated COOL, the statute does not permit labels detailing where animals were born, raised and slaughtered, which is what the final rule requires.

Kelsey, who grew up in Rush Springs, Oklahoma, and earned a BS degree in animal science from Oklahoma State University in 1992, comes from a similar job with the Nebraska Cattlemen's Association.

Growing up in Oklahoma and showing cattle while he was in school, Kelsey is familiar with two problems which have bedeviled cattlemen for generations. These problems are heat and lack of rain.

Due to the current severe drought which began in late 2010, Oklahoma cattlemen were forced to sell off over one-third of the state's beef herd. Continuing drought conditions, as well as extraordinarily high prices demanded for cattle due to the small number available, make it problematic for anyone trying to increase a herd or get back in the business, Kelsey said.

"I recently talked with a rancher who lives in the Oklahoma Panhandle where it is really dry," he said. "He told me the only thing keeping him going is faith it will rain again. I believe cattlemen and farmers are real optimists. If they weren't, they wouldn't be in the business. Making a living off the land, particularly where you rely on grass and water for your cattle, requires faith and optimism of the highest order.

"Ranchers are dedicated to the stewardship of their land. They know they must take care of their pastures and water supplies, do the best job they can to rotate pastures and keep their water sources in good shape."

On a more local level, Kenneth Holloway, owner of the Coyote Hills Ranch near Chattanooga, Oklahoma, in Tillman County, struggles with the current drought every day.

"We have sold down our cow herd to half of what it usually is due to the extreme drought," he said. "We had to reduce our numbers to protect our pastures so we wouldn't graze out our grass. While we did get some rain earlier in the spring, it now looks like hot, dry weather will be the rule for the future."

Holloway remembers his father struggling to keep his cattle herd during the bad drought of the late 1950s. "I understand it was worse than the one we have today," he said. "At least I think it lasted longer, but this one isn't over yet. It may outlast that one."

Holloway remembers the scary stories his mother told him about her early life in the Dust Bowl days of the 1930s when thousands of people were forced from Oklahoma farms by continuous drought. The best part of those stories is that people have learned how to do a better job of taking care of the land, he said. "Farmers practice no-till and rotate crops and ranchers limit the number of cattle they place in a pasture to its best carrying capacity, so we know how to cope better now and prevent much of the worst results of prolonged dry weather," he said.

Still dry

Water availability for his cattle to drink has been Holloway's biggest problem. "All of our ponds, with the exception on one that is fed by a spring, have been dry for a long time," he said. "It just hasn't rained enough to get any runoff water to fill our ponds. What rainfall we received stayed where it fell because the cracks in the ground were so big."

If weren't for water being available from rural water company waterlines, Holloway wouldn't have any water except for one spring-fed pond. "Rural water availability has kept us going for nearly three years now," he said.

Also of interest:

Cattle producers watching future with “guarded optimism”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like