At Shirk Catfish Farm, management plan is to 'take care of the little things'

“The production system on our farm is fairly typical of commercial catfish operations in this area," says Kevin Shirk of the 103.5-acres he and his wife, Edith, have near Brooksville, Miss. "Unlike some farms here, however, catfish is our only enterprise. We attempt to do a superior job of managing our operation, which we feel gives us a competitive advantage. Since we started operation in 1997, we've not had a year that we didn't show a profit."

Mississippi, the nation’s No. 1 farm raised catfish production state, has seen a precipitous overall decline in acres in recent years as farmers, unhappy with prices and profit margins, have converted ponds to crops, the Conservation Reserve Program, or reservoirs for irrigation of row crops.

From 2009 to 2012, total acres in the state dropped from 80,200 to 51,200, according to the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service, with the bulk of the decline in the south Delta, where the majority of production is located.

But for Kevin M. Shirk and his wife, Edith, who operate Shirk Catfish Farm near Brooksville, Miss., fish production remains a viable — and profitable — enterprise. Noxubee County, in the Black Prairie region of east Mississippi where their farm is located, ranks fourth in pond acres statewide and No. 1 outside the Delta.

“There has been some attrition in the catfish industry on this side of the state,” Kevin says, “but the decline hasn’t been as sharp as in the Delta. One difference, I think, is that most of the operations here are family-owned, and more hands-on management oriented, with family members providing most or all of the labor.

“On our farm, Edith has worked right alongside me, and our six children and 14 grandchildren help and fill in when there is a need we can’t handle.”

The area has a very good catfish production infrastructure, he says, with a number of small and medium size family-run operations. The heavy soils in the region are ideal for catfish ponds.

“The production system on our farm is fairly typical of commercial catfish operations in this area. Unlike some farms here, however, catfish is our only enterprise. We attempt to do a superior job of managing our operation, which we feel gives us a competitive advantage.

“Last year, catfish prices were good, and our margins were good. Right now, prices are running about 95 cents a pound net, down from $1.25, and I think there is market pressure for the price to drop even more.

“Since we started operation in 1997, we’ve not had a year that we didn’t show a profit. The worst year we’ve had was an average 42.5 cents per pound. Thankfully, it was a good production year and we still showed a profit — just barely. But, like row crop farmers, our input costs keep escalating. I’m projecting average feed cost this year of $386 per ton, up from $354 last year.”

His management philosophy, Kevin says, is to “take care of all the little things. The big things are a given, but at the end of the day, I look for one more thing to add to my list of things to do to be as efficient as possible.”

A high production fish farm is a 24/7 job, he says. “I’m out checking the ponds three or four times a night, catching sleep when I can. But I love working with fish, and the Lord has blessed us with success.”

Before coming to Mississippi in 1997, Kevin was part of a family dairying operation in Michigan.

“We had a 120-cow herd, and there was pressure to get larger to be more financially viable. I went to the bank and got a loan for a new milking barn, but before the contractor started moving dirt I asked myself, ‘Do I really want to take on this debt?’ And after careful consideration, my answer was ‘no’.

“My brother, Paul, was growing hogs and catfish here in Mississippi. I’ve always loved to fish and I thought it would be great to be able to make a living with fish. So, we moved here in 1997, bought some pastureland, and put in our first ponds in April that year.”

Consistently high production

Now, the operation consists of 103.5 water acres in 10 ponds. Kevin and Edith own 65.5 acres and rent 38 acres from their son, Kevin R. Shirk, who got out of catfish to concentrate on poultry and row crops. The catfish farm is operated as a multi-stock grow-out system, with per acre production consistently above industry averages.

“Our primary product is channel catfish,” Kevin says. “We’ve experimented with hybrid cross catfish (channel/blue), but we’ve found that in our operation they have a negative impact. Due to cannibalism, they must be grown as a single batch in a pond. Our multi-batched channel catfish have a significantly higher production history than single batch hybrids. We’re keeping a close watch on developments in hybrid production, and we’ll try them again if we feel we can realize an economic benefit.”

The Shirks buy three- to four-inch fingerlings from Thompson Fisheries at Yazoo City, Miss., and raise them to seven- to nine-inch stockers, which are then moved to grow-out ponds for finishing to approximately 1.8 pounds and about 18 inches in length.

“We try to tailor fish size to what the market wants,” Kevin says, “so, size will vary some year to year. Raising our own stockers gives us advantages of availability when needed and cost savings for fingerlings, plus our home-grown stockers finish much faster than those shipped into our area from the Delta.”

Fingerlings are started on 35 percent protein pellets. “A key to making a nice profit with fingerlings is survivability,” he says. “The industry norm is 60 percent survival —we consistently run above 85 percent.

“Stockers are moved to grow-out ponds twice yearly — about 5,000 fish per acre are put into each pond in July or August, and the remainder are transferred in January. We use Sam Saul Seining Service to move our stockers. He does a good job, is dependable and fast, and is our least expensive option for that operation.

“We use 28 percent protein feed, mostly from Land O’ Lakes at nearby Macon, Miss. They have consistently given us good feed, good service, and good results at a competitive price. We book feed ahead when we can lock in a price that will give us a profit. We follow Chicago Board of Trade prices daily, which helps us keep ahead of local market price movements.

“Our strategy has been to give each fish as much feed as it will eat each day. In peak growing season, we feed twice daily, starting when water temperature stays above 80 degrees. This increases feed consumption about 10 percent, but it pays off in production.

“Quality and grade for our finished catfish have been excellent, which has resulted in good demand from processors. We attribute this to the extra care in general husbandry practices, particularly feeding and aeration.

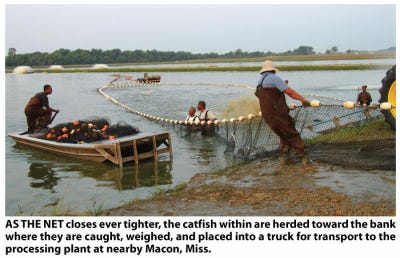

“We sell our fish direct to processors. Superior Catfish at nearby Macon, Miss., is our primary contract harvester and buyer.”

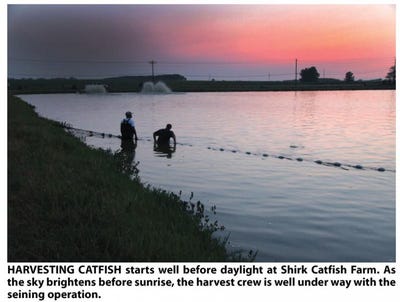

Each pond is harvested two or three times per year, Kevin says, normally in June, August, and mid-winter. “These times seem to be when there is a lull in other farmers’ harvest schedules, and it’s much easier to sell then.

“Three times is also ideal for our goal of selling 1.8 pound fish, a size that seems ideal for maximum annual production, and a size that’s in demand in the marketplace. Research has shown that channel catfish loose feed conversion efficiency when they are larger than two pounds.

“With the high demand for catfish this year, we have increased our stocking density to 13,000 fish per acre in order to harvest smaller fish more often. When demand slackens and processors ask for larger fish, we will resume a 10,000 per acre stocking rate.”

Constant oxygen monitoring

The most common problem they encounter in daily pond management, Kevin says, is keeping the dissolved oxygen level high enough at night to keep fish from feeling stress.

“We manage this with aeration. We monitor oxygen levels with a Campbell Scientific automated control and monitoring system that checks parts per million of dissolved oxygen every 20 seconds and transmits the information to my cell phone. Each aerator can be set, controlled, and monitored individually, and it will turn aerators on and off at set points we choose.

“Our 10 horsepower electric floating paddlewheel aerators are from Aerway Mfg., and we use two to six of these per pond, depending on acreage and availability of power. Most of our ponds have the maximum load allowed by our power supplier, 4 County Electric Power Association.

“Five horsepower per acre is our highest aeration level, 3.85 horsepower per acre our lowest. Even in ponds with 5 horsepower per acre, production has increased when aeration is increased. So, we’ll continue adding aerators as time and availability permit.”

They have been buying used aerators from farms quitting production, Kevin says, “but we’re no longer able to find good used aerators, so we’ve been buying new ones from Aerway Mfg.”

Tractor backup aerators are used every night during production season. They have 13 diesel power units and tractor aerators.

“We’ve been starting the backup aerators at about 2 to 2.5 parts per million of dissolved oxygen,” he says, “compared to the industry norm of starting when fish pack behind the aerators.

“Our goal is to never see a fish until they’re seined at harvest. If I see fish packed behind the aerators, I know there’s some reason they aren’t comfortable and that I’m losing production because they aren’t eating and growing as they should.”

Diseases can also be troublesome, Kevin says, and in 2010 and 2011 outbreaks of Aromonos hydrophila resulted in significant losses.

“In 2009, it caused major losses in the Alabama catfish industry, and since then seems to have been spreading westward. It happens with great rapidity: one day you may have 25 dead fish, the next day 2,500, the next day 25,000.

“It just explodes, and when it hits it seems there’s nothing you can do. It is the only part of catfish production today for which I have no solution. Medicated feed seems to help, but by the time you can start feeding you’ll have thousands of dead fish.

“In 2010, we lost 100,000 pounds of fish to the disease and last year 250,000 pounds. Fortunately, catfish prices offset the losses, but still it’s the kind of financial blow you don’t like to have.

“The potential for major losses to the industry is scary. Right now, other than catfish imports, it’s our biggest challenge. Scientists at the Delta Research and Extension Center at Stoneville are working on it, and we hope a solution can quickly be found.”

Charlie Hogue, Warm Water Pond Management, is the Shirks’ consultant, and Craig Miller tests ponds weekly for water quality.

Imports taking market share

Imported catfish, which can be produced so much more cheaply, has been a widespread problem for the industry, Kevin says. “Imports have taken a lot of the market share of U.S. farm-raised catfish. The continuing challenge for our industry is to make consumers aware of the superior quality of our farm-raised fish.”

Fish-gobbling cormorants and blue herons have become more of a problem in the area over the past two years, he says. “Flyway patterns seem to be changing, and we’re seeing greater numbers of the birds. They can eat a lot of fish, and it’s an everyday chore trying to chase them away.”

Initially, the Shirks were relying on rainfall to keep water replenished in the ponds. “But five years ago, we drilled wells on both farms,” Kevin says. “It was a fortunate move, as it turned out, because of the severe drought that year. We were able to have adequate water for all our ponds and maintain full production. The wells were drilled to a depth of 1,135 feet to get a 295 gallons per minute flow.”

The Shirks also have a herd of 20 Brangus beef cow-calf pairs. “While they’re not a profit enterprise, we use them to graze pond levees and perimeters, which saves the cost and labor that would be required to mow these areas,” Kevin says.

“We utilize artificial insemination to get the best cattle possible genetically. Bull calves are sold as steers at 500 pounds; heifer calves are all saved for future feeding stock.”

Suppliers are important to their business, he says, “and we’ve enjoyed good relationships with all of ours. Others in the farming community have been helpful with advice and assistance. The late Harvey Miller, one of the original east Mississippi catfish farmers, was a great source of advice and encouragement to me when I was starting out in this business. He always had time for me and was always generous in sharing his expertise, and I’m grateful for his friendship. We’ve been appreciative, too, of the work that the Mississippi State University Extension and Delta Research and Extension Center specialists provide.”

Since he and Edith constitute the entire labor/management force, Kevin says, “We’re stretched about as far as we can go,” and no expansion is contemplated at present.

“While this arrangement allows us to sell more pounds of fish than the industry standard, it limits our being able to take time off, increases the burden if one of us is sick, and delays the implementation of changes in our production practices. In mid- to late summer, we just plain get tired, and that, too, becomes a limiting factor for production.

“Looking ahead, our business and family goals are to provide employment and income for Edith and me, and to keep production and profit levels as high as we can, with at least a small increase each year.

“I have no intention of retiring, as long as I’m in good health, but in about five years we’d like take on a partner with the future goal of that partner taking over management of the operation so Edith and I can phase out of the day-to-day requirements of the business..

“In the meantime, our overriding goal is to continue to serve God as the best stewards we can be, and to have the joy of helping our family and others.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like