In agriculture, prices will go where they have to go. When corn prices dropped from $4.50 to $3.70 per bushel a few years ago, farmers naturally complained: “But it costs me $5 per bushel to raise corn.”

In fact, your cost structure has little to do with what the price of corn will be in the short run. If corn is at $3.50, your cost structure must adjust or you go out of business, unless something else is subsidizing your farm.

In agriculture’s case, boom years are the exception, not the rule. The trick is to nimbly manage costs during tougher “normal” years.

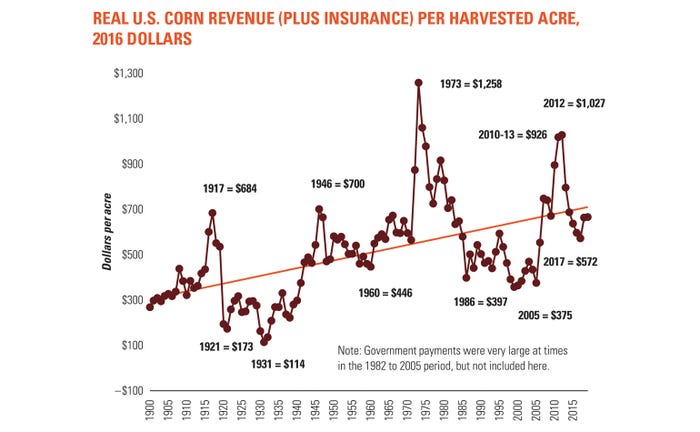

Purdue economist Chris Hurt describes a long-term, 29-year price cycle in agriculture: 10 years of a base price, a few years of a launch price, a few more when prices peak, and then a few more where they soften (landing price), followed by 10 more years of a new equilibrium price. Right now we’re still in the landing stage.

While the cycle is only theory, are there ways to make better decisions if and when you are convinced the cycle is changing?

“You should be aggressive in the early part of the launch, and in the later part, you should start to pull your horns in — start thinking about survival strategies that are coming in the landing era, where prices drop and costs stay high, which is usually four to seven years,” says Hurt. “Then you will have more stability.”

Of course, it’s easy to offer that advice after the fact. When corn is rallying to $8, as it did five years ago, it’s hard to think about caution. Instead, people start thinking they are in a new plateau. The sky’s the limit. Fixed and input costs get bid up. You write big rent checks because you’re clearing $500 an acre in revenue. Then production reacts to price, supplies pile up and everything comes back to earth.

That adjustment takes time. That’s the nature of commodity farming.

Irreversible supply curve

After corn prices hit the stratosphere five years ago, few people wanted to think about the long-term consequences. But the laws of supply and demand are fairly predictable, and greed is a universal human condition. Higher prices led to more grain acres worldwide. That growth, along with better technology and remarkably few weather hiccups the past five years, has led to the current grain surplus.

“Once you clear land and bring it into production, people are not going to go back and plant trees,” says Hurt. “Once you bring technology, irrigation or other investments in, you’re not going to stop producing. In economics it’s called the irreversible supply curve: When prices of grain go up, you bring more land into play. In the U.S. it was mainly through conservation reserve; in the rest of the world, it was just new acres.”

While the U.S. may not have added that many acres, it does have its own version of this irreversible supply curve. The U.S. has been blessed with educated, management-oriented farmers and non-farming investors excited to jump into the farming game.

We’re farming with better seed, ag technology and long-term investments like tile and irrigation — stuff that would make grandfather’s head spin. How do you move to that kind of farming and then say, “Oh, I want to reverse course”? That’s not going to happen.

If the global cost to produce corn is lower than current sale prices, there will — eventually — be a reduction in supply. But from where? Who will blink first? The irreversible supply curve is a ruthless master.

“You can go multiple years before there has to be a pervasive attitude that there is no money in farming, or that buying land is a bad investment that gives you poor returns compared to other alternatives, especially to nonfarm investors,” says Hurt. “Such discouragement might curtail production increases.”

Signs of a turnaround

World acreage for major crops has leveled off for the last three years, so that discouragement factor is taking place. Those peak 2012 prices sparked ag development projects worldwide. Cropland went into production despite falling prices, but the rate of increase has slowed considerably.

Expansion will continue in South America. Argentina has pasture that can be converted to crops, and there’s still a huge swath of land in Brazil ripe for conversion. The former Soviet Union countries are still expanding, but profitability has dwindled, so that growth may ebb.

If growth in demand catches up to supply, there will be less need to curtail production. Demand is increasing as the world economy is finally hitting on all cylinders nine years after the recession. All major countries show economic growth, so that’s a real positive. World income growth is the best overall since 2008. The dollar is weakening, helping overseas sales.

World yields have been on a lucky streak the past four or five years — above trend for most major commodities. The odds say that can’t continue. There have been weather disruptions, but worldwide we have had very good conditions, and yields reflect that. Technology helped reduce impacts of disease and mitigated yield variability to some degree. But for the most part, weather has been the main driver of higher world production.

“Globally, we won’t likely have that trend continue,” concludes Hurt. “You would then see some recovery, and most farmers who have adjusted costs will say they can make it fine with $4 corn.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like