We are losing about 1.8 million tons of soil per year to soil erosion in the U.S., costing 2 pounds of soil for every pound of corn we produce. That's what Jerry Hatfield, laboratory director at the USDA Agricultural Research Service’s Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment, told farmers at the Nebraska Farmers Union state convention held recently in Columbus.

"We've underestimated how important soil is," Hatfield told the group. "If we are dependent on rainfall, soil quality makes yield." Hatfield said that organic matter and soil health are crucial to the water-holding capacity of the soil. "If you don't have the water, you don't have the crop," he said. With the water needs of crops often coinciding with drought conditions or heavy rain events, the ability for the soil to absorb and hold water without allowing it to run off is a key element to yield. "It's not how much water we have in the rain gauge that counts," Hatfield said. "It's how much rain that actually got in the soil."

Changes in organic matter impact nutrient cycling, soil structure and water availability in the soil, he said. That's why no-till practices make a difference in soil health. "But if residue is removed in a no-till system, it hurts the soil," he said. "It is how we manage a no-till system that makes it effective."

Residue helps soil absorb rainfall and protects it from drying out. It is also crucial in modifying the microclimate to allow soil microbes to exist. That's why farmers also need to manage the biology in the soil. "To stabilize the soil biology, we need food, water, air and shelter — the same as people," he said. Cover crops help feed soil biology from one growing season into another.

"Diversity above the soil surface also creates diversity below the surface," he added. "Really healthy soil is feeding the equivalent weight of two elephants per acre of microbes below the soil," Hatfield said. "That's why we refer to the soil as a living system."

What’s ‘conventional’ tillage these days?

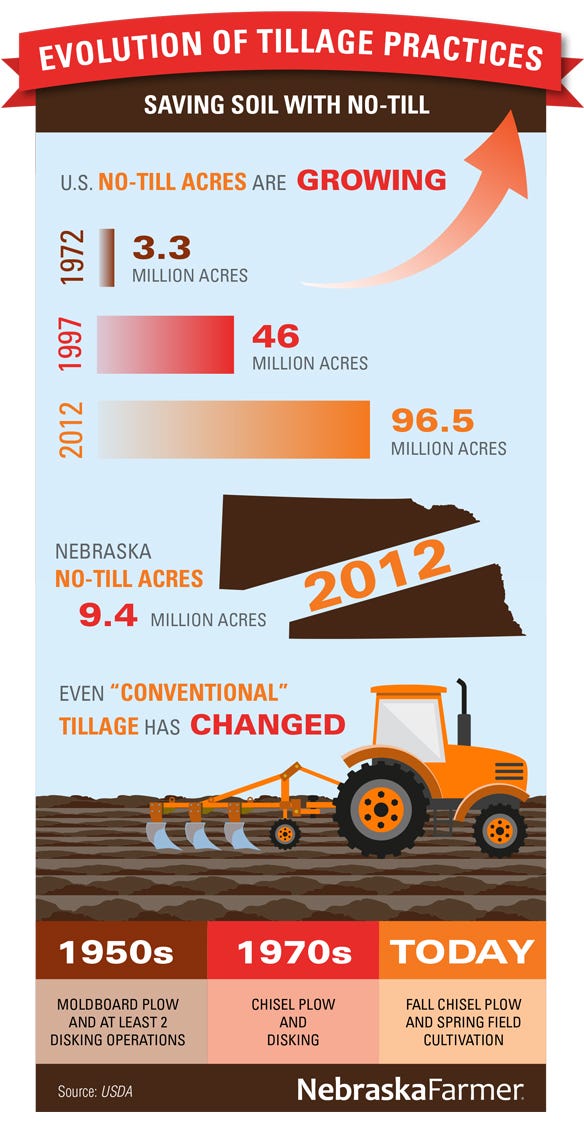

In his talk to Nebraska Farmers Union members, Hatfield presented findings from studies comparing soil erosion under conventional tillage systems to no-till or strip tillage. In a separate interview, Hatfield acknowledges that what USDA considers as "conventional" or normal tillage has changed over the years with farmer practices in the field. "I try to show that conventional in the 1950s is not conventional in the 1990s or 2010s," Hatfield says.

"In the 1950s, conventional tillage would have been a moldboard plow with at least two disking operations in the spring before planting," Hatfield explains. "In the 1970s, the plow would have been replaced with a chisel plow with still aggressive tilling before planting. By the 1990s, we still had the chisel plow in the fall combined with anhydrous application following soybeans, with a light field cultivator in the spring," he says. "By this time, some producers had begun reducing tillage operations for corn going into soybeans."

Increasingly, no tillage and varied forms of conservation tillage have become more "conventional," at least according to USDA Economic Research Service statistics. No-till practices probably comprised only about 3.3 million acres in the U.S. back in 1972. According to the 2012 Census of Agriculture, those acres have grown to 96.5 million acres today. Nebraska consistently ranks among the top five states in no-till adoption, covering about 9.4 million acres, or 42% of the state's cropland.

"I would like to see conventional tillage be no-till or strip-tillage systems," Hatfield says. "In terms of a definition, we still think of conventional tillage as a chisel plow operation in the fall and field cultivation in the spring before planting."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like