When Hans Bishop asked his father, Dave, if he could have a salaried position on the family farm after 10 years in the insurance business, his father flat-out told him no.

“It’s probably a good thing he said no, because he had a small vegetable enterprise going in addition to row cropping and livestock. After he said no, I asked if I could expand on the vegetable enterprise. He said, ‘Now there’s an opportunity,’” Hans recalls.

With Hans on board, the 480-acre family farm in Atlanta, Ill., grew from having a half-acre in organic vegetables to 30 acres and four hoophouses as Hans and his wife, Katie, expanded their sales across Bloomington, Champaign and Chicago.

“We’re a testament to saying you can make a living farming organic,” Hans says, adding that expanding the vegetable operation was the only way to support a second family on their farm. He also helps his father manage organic-fed livestock and raise organic corn, soybeans and wheat.

A year ago, the Bishops opened a food processing center called PrairiErth Food Hub to send shipments to Fresh Picks Farmer Alliance Food Hub in Chicago, as well as to various restaurants and downstate grocers.

“The idea with PrairiErth Food Hub is the neighbors see what we’re doing, get curious, put out a half-acre of something we’re not growing, and then we help facilitate the delivery arrangements and pay someone to market it so there’s consistent demand,” Hans says. “It’s something that wasn’t here when I was starting.”

PrairiErth is one of at least three new organic food processors built within the past year in Illinois. The others include an organic grain mill near Champaign and an organic poultry processor in Petersburg.

“With all the new infrastructure, I would suggest that things are starting to change fairly rapidly. Organic isn’t so niche anymore,” Dave Bishop says, adding that while farmers markets take in about $1 billion a year, grocery stores have rising demand for organic vegetables, grains and organic-fed livestock products.

“The market share for farmers markets is probably around 2%. But it’s clear organic is growing fast outside of that,” Dave says.

Rewards

Farmers wounded by trade wars and high input costs are eyeing ways to diversify: from growing specialty crops such as white corn or high-protein soybeans, to growing non-GMO soy at a dollar more per bushel, to growing organic-certified grain for more than $2 a bushel.

“If you’re a conventional corn-soybean farmer, you should look at all the options and see what fits you,” says Dave, who also runs a consulting business for farmers. “It may not be organic. It might be much easier to incorporate hemp into your operation, for example, as those markets develop.”

LEAFY GREEN Dave Bishop grows leafy greens such as romaine lettuce year-round in the family farm’s temperate hoophouses.

All options offer different revenue streams than conventional corn and soybeans, but organic offers a consistently higher premium, says Rich Ritter of Flanagan State Bank. He doesn’t shy away from lending to farms interested in diversifying.

“We work with conventional farmers, too, of course. The only difference is your margins are thinner right now based on the situation we’ve got. That could all change,” Ritter says. “Organic is not a fad, though. This is the real deal, and it’s here to stay.”

Today, organic growing has spread out from the coasts into the Corn Belt, adds Ken Dallmier, Clarkson Grain chief operating officer.

“It’s not just farmers markets anymore,” Dallmier says. “Most of the feed going to organic meat is imported, but more and more farmers in the Midwest are tapping into the market.”

Ritter says he’s getting frequent calls from landowners interested in transitioning to organic, a process that includes a three-year transition period where farmers can’t use prohibited fertilizers and crop protection chemicals. After three years, they harvest their first USDA certified organic crop. The transition period inevitably leads to losses, as farmers raise organic crops but can’t sell them for the premium.

In surveying organic farmers in Illinois in the past, Ritter was shocked at the number of growers who had to go organic without landlord or lender support — instead borrowing from family credit cards or against equity on personal assets.

He says farmers could lose $100 to $200 an acre in what often amounts to two transition harvests.

“To the landowners, I say, ‘These folks are going to make your land worth more money because it’s going to be certified, and if they can generate another $150 to $200 an acre when the dust settles, then you need to help them in those first two years,’” Ritter says.

With new advantages to organic under USDA’s Whole-Farm Revenue Program crop insurance, Ritter says more lenders are warming up to funding organic diversification.

Organic farmers now have the option to take a higher price guarantee for their crop if they harvest before July. They can choose between the prior year��’s price guarantee or the current year’s.

“You have higher crop insurance, you have growing markets, and you have more income. That’s why I’m excited about organics,” Ritter says.

Challenges

Outside of financials, diversifying into organic is a challenge for conventional farmers because organic fertilizers, herbicides and fungicides are more expensive than conventional. Organic production also comes with a steep learning curve.

While organic crops have a higher premium, Dave Bishop says new organic farmers can still find themselves “in a world of hurt” if they don’t dip their toes in the right way — gradually, with a focus on reducing input costs.

In his area, he often advises farmers transitioning to organic to start out their first year with a non-GMO soybean contract. He also advises starting out on a small tract of land rather than 2,000 acres.

“Then after the harvest, you might no-till wheat. And then come February the following year, we would frost-seed some cover crops into that for nitrogen,” he says.

“The year after that, you’d put an organic corn crop out there. Ideally, you’re pasturing it, too, to really reduce your inputs, make more green-brown fertilizer, and get more value from that wheat acre,” he adds. From there, it’s a three- to four-year crop rotation, with money-making plantings of organic corn and soybean separated by wheat, cover crops and hay.

The crop rotation helps to minimize disease pressure, though it presents a host of new management decisions for farmers used to two-crop rotations. For example, rather than spray an organic fungicide, they may find cheaper ways to fight the same pest using cover crops or different crop cycles.

Dave cautions that some farmers looking to diversify may stay content with the higher premium offered by non-GMO soybean contracts.

“That’s perfectly viable. You don’t have to be afraid the weeds will get you.There are options,” he says, pointing to physical methods of disease control like zapping with electricity. “It’s pretty apparent we need to add diversity to farms. Organic is one way, but there are others.”

PRESERVED: Clarkson Grain moves soybeans on pallets and trucks through its Mattoon, Ill., facility, deploying various techniques to keep the specialty grains from cross-contamination.

The value of ‘identity preserved’

The 114-bin Clarkson Grain Co. elevator in Mattoon, Ill., is unconventional compared to other bulk grain storage elevators throughout the state. Uniquely, the facility specializes in moving “identity preserved” soybeans, which ranges from high-protein varieties of the crop to non-GMO and certified organic.

“We store and process identity preserved food and feed,” Dallmier says, adding that they deploy advanced cleaning methods to keep shipments of trucks and pallets from becoming cross-contaminated.

By keeping so many bins of soybeans grown for specific, high-premium markets, Dallmier says Clarkson has positioned itself for the future — a future that sees such markets growing.

U.S. organic livestock production is in high demand, with dairy, poultry and other markets importing far more organic feed than the U.S. currently produces. The organic industry has grown double-digit percentage points every year for the past 10 years in the U.S.

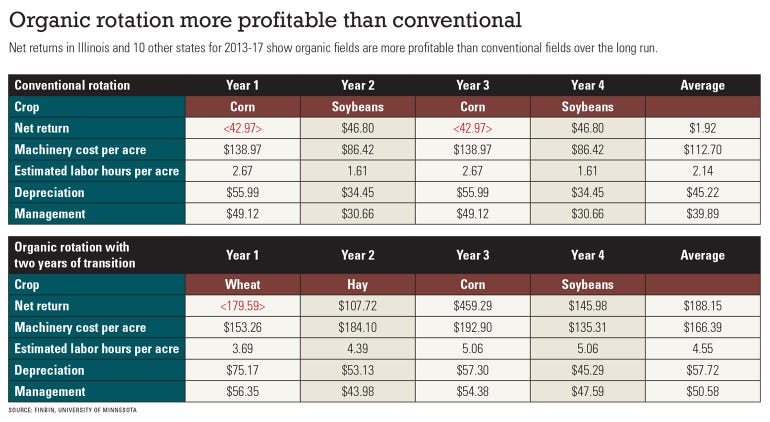

In this growing market, businesses are paying two to three times above commodity cash prices. That’s a rule of thumb that will likely remain constant, Ritter says. The number holds true even when organic and conventional commodity prices hit their worst-case lows, according to 2013-17 data from 11 states collected by the University of Minnesota.

“The yields are better in Illinois than those averages reflect, but I wanted consistent data to say, OK, the organic crop yields might be higher in Illinois, but so would the conventional. I’m more interested in the relationships,” Ritter says.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like