Craig Chase, Iowa State University Extension and Outreach director for value-added agriculture and local foods programs, says many new farmers love the idea of farming — working outdoors, getting their hands dirty, raising food and providing goods to customers. But there’s one thing specialty food growers need to understand before diving into a new business venture: It’s work. Especially as a sole income source.

Chase asked three established specialty crop producers to log the time they spent with each crop, including planting, weeding, fertilizing and harvesting. One 100-by-4-foot green bean bed required 28 hours of labor.

“They had no idea they spent that much time,” Chase says, adding that those clocked hours were used to develop enterprise budget templates for farmers considering new specialty crop businesses.

“The most important thing is the least amount of fun — recordkeeping,” Chase says. “Being able to say growing this is costing this much, and I need to make this much for me to continue my business.”

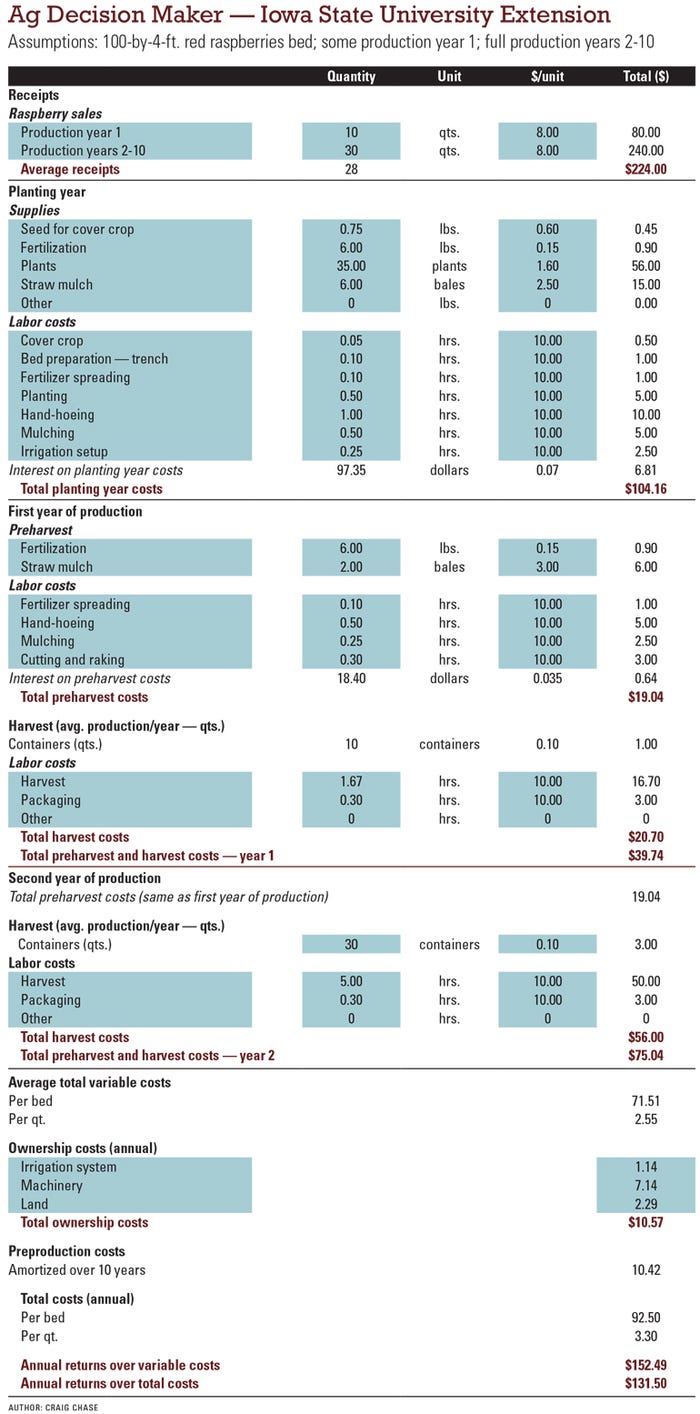

Every new business should begin with an enterprise budget that outlines expenses and potential profit, he says, especially for the top three potential crops. What does an enterprise budget look like? Here’s an example for one 100-by-4-foot raspberry bed:

This is one crop and one plant bed. The average specialty farmer plants several different crops and can achieve a net profit of $5,000 to $6,000 per acre, Chase says. “The problem is that any individual farmer will max out her or his labor at about 2 acres, so they work hard all year for $10,000 to $12,000.”

The next step? Expansion.

As the Hultines recognize, expansion requires extra hands and means higher costs, lower profit margins and more customers.

“Selling direct becomes more difficult as you need more and more customers through either your CSA [Community-Supported Agriculture] or at farmers markets,” Chase says, adding that selling to nondirect markets is a consideration, but the pricing structure is very different depending on the product and market.

Expansion itself can be a challenge without adequate land. Farmers may add high tunnels or greenhouses into the farming operation instead of acquiring more land, Chase notes, but additional labor needs and marketing are still an obstacle.

“If we want to talk bottom line, for a produce farm to be sustainable on its own, it would need to have a minimum of 6 to 8 acres; two to three high tunnels; a manager that understood production, finances and marketing; and could deal with a labor force that may or may not be experienced with produce,” Chase says. “I have seen too many energetic, passionate, eager beginning farmers burn out because they had a dream of living on 2 acres and being full-time farmers.”

Check out more enterprise budget templates.

Expectations by the acre

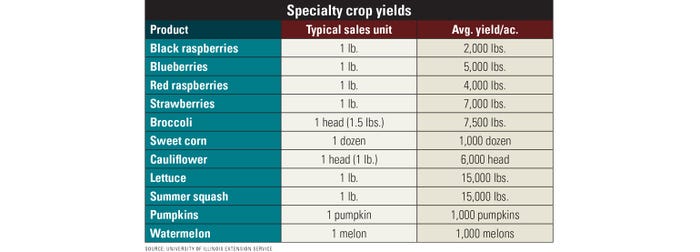

If one specialty farmer has the potential to manage 2 acres, how much could he or she grow? Nathan Johanning, University of Illinois Extension educator, says specialty crop production can start with an acre, a good tiller, hand tools, baskets and elbow grease. Like row crops, yield will vary by soil types and production practices, but here’s a look at common farmers market products and average yields per acre.

It takes more than a green thumb to build a specialty crop business, Johanning adds, and marketing is key. “If you’re willing to work, there is return there,” he says. “But it doesn’t fall in your lap.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like