Weather extremes challenge corn nitrogen management

Think differentN risk management advice in a nutshell:Time in-ground and wild, wet springs reduce N availability.Delay N applications on lighter soils until spring.Don’t count on one-time fall-applied or even early spring-applied N to be there when and where corn needs it.Get more efficient N use by piggybacking N application with other field trips—apply N in as many operations as you can.Sidedress as soon as you can.Save N adjustments until final sidedress, then apply according to soil tests.Don’t fall-apply N on high-pH soils.

August 1, 2013

Nitrogen management is entirely about risk management, especially this year. “There’s an economic risk of wasting money and being seen as environmentally reckless by applying too much N, and a risk of corn yield loss from applying too little,” says Dan Frieberg, president of Premier Crop Systems, LLC, in West Des Moines, Iowa. “But there’s also a risk that’s not talked about much — allowing nitrogen-management decisions to adversely affect other crop-production operations.”

With such wild and crazy weather, when you don’t know if you’ll be facing floods, droughts, both or something in between, how can you decide on a nitrogen (N) management plan?

Wet years tough for N management

“This was a difficult year for nitrogen management,” says Jeff Vetsch, research scientist at the University of Minnesota’s Southern Research and Outreach Center at Waseca, MN. “Normally, using a nitrogen inhibitor in the fall would save most of the nitrogen for the spring crop, but this spring, we figure we lost as much as half of the fall-applied nitrogen because of the wet April and May.”

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to CSD Extra and get the latest news right to your inbox!

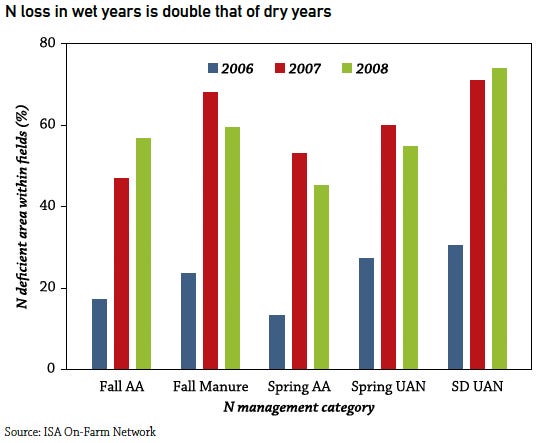

Peter Kyveryga, senior research associate at the Iowa Soybean Association On-Farm Network, found the same thing surveying data from more than 800 ISA on-farm evaluation fields in Iowa in a wet 2007 and extremely wet 2008 year. Cornstalk nitrate tests taken in those years on corn after soybean fields showed more than half the field areas were N deficient. He also found in the two wet years, the average N-deficient areas were significantly larger for fall anhydrous ammonia, fall manure, and spring-applied UAN than for spring-applied anhydrous ammonia. Fall injected hog manure lost a large percentage of N. The percentage of N-deficient areas was more than twice as large as in a relatively dry year, 2006. Total N rates had no effect on the size of N-deficient areas. The size of N-deficient areas was affected by N form, timing and rainfall.

A number of studies have shown traditional N recommendations based on yield goals have missed the mark because of weather-driven variability in N supply from the soil and losses to leaching, volatilization and denitrification. In seven Corn Belt states, N rate recommendations can be calculated with maximum return and profitable N goals — see the Corn Nitrogen Rate Calculator online.

Wet years (red and green bars) had at least twice the N-deficient areas as the dry year (blue bar) consistently across all five categories of N management. (Results are from 800 field trials by the Iowa Soybean Association’s On-Farm Network. The deficiency was measured with cornstalk nitrate tests and aerial imagery.)

Move toward spring applications, but see a bigger picture

“Getting the crop in the ground during the optimum spring planting window is the most significant of any of the risks,” says Frieberg, who has the benefit of reviewing precision ag production data from farms across the Midwest. “Too often in the real world, Mother Nature gives us only 10 to 15 days fit for field operations in that optimum planting window and you don’t want to be caught missing an optimum planting day because you’re taking that day to apply nitrogen. 2013 is going to be a dramatic example of just how important it is to plant when it’s fit—in the Upper Midwest, we’ll have more of the world’s most productive fields that didn’t get planted to a crop than any time I can remember.”

. Beyond yield loss for late planting, it’s important to factor in the potential cost of drying corn if planting is delayed too long.Still, Frieberg’s recommendation is to delay N applications on lighter soils until spring, and on well-drained heavy soils, fall-apply no more than 60% of total expected N needed as anhydrous ammonia with an N inhibitor.

“Nitrogen management has so many variables across the Corn Belt that it’s misleading to make recommendations that apply across the board. But in general, my strategy would be to save your N adjustments until spring,” Frieberg advises. “It’s still a guess then, but in the fall, it’s a total guess. You can apply more nitrogen preplant, at planting, or as sidedress. Sidedress as soon as possible—don’t wait until the week corn will close the row. If you split hairs over sidedress timing, the weather could shut you out again.”

Waiting until spring to apply N is pretty much a given for most of independent crop consultant Damon Winterrowd’s clients.

“We have very little fall N application in our area, CropStar crop consultant Winterrowd says. “Late June and July is a high nitrogen demand period for corn—even if you put it all on before planting in April a lot of things can happen to that N. You want to know the N is there when the plant is growing—not just hope it’s going to be available.”

So Winterrowd’s first discussion with growers involves avoiding single applications. “You spread your risk if you make as many applications of N as you can, with other field operations. Put some on preplant, apply some with the planter, maybe mix some with herbicides—the more applications you can make, the better,” Winterrowd says. “Then use tests like the late spring nitrate soil test to analyze remaining needs, and make adjustments at your final sidedress.” Winterrowd also recommends trying two N stabilization products, and testing their effectiveness through yield comparisons and cornstalk nitrate tests.

The University of Minnesota has a time-tested, simple decision tool Vetsch says can be used in lieu of late-spring soil N tests to estimate N losses and guide decisions on supplemental N needs as sidedress. The guide uses a point system with multiple-choice answers to these three questions:

1) When was the fertilizer N applied?

2) What was the predominant May soil moisture condition?

3) How does the corn look today?

The answers to the questions result in points that either recommends sidedressing at 40-70 pounds of N/acre, recalculating in a few days, or applying no additional N. See the worksheet online.

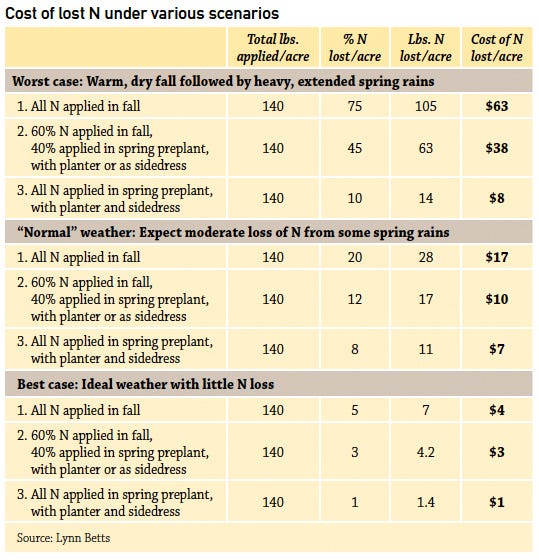

N losses from weather conditions are highly variable, but you can limit your N risk. This chart shows that at 60 cents a pound, a fall N application could cost you more than $60 an acre if you lose 75% of 140 pounds per acre applied in the fall in a worst-case scenario. Split applications cut the risk.

Extreme rain events cut profits

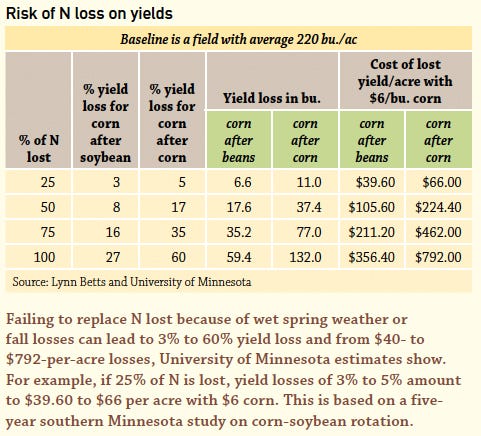

It’s bad enough when heavy rains and saturated soils wash away your applied N investment. But you really compound the economic risk if you fail to replace it, says Jeff Vetsch of the University of Minnesota. Vetsch used a 5-year yield response to various rates of N study to estimate how much yield would be lost if 25, 50, 75 and 100% of the N was lost.

In his estimates, yields from fields with no N loss averaged 220 bu./acre. He figures that if 75% of the N was lost, in continuous corn, an estimated 35% yield loss would amount to 77 bushels and $462/acre! Even a much more moderate loss of 25% of N lost and not replaced in a continuous-corn field would result in an estimated 11-bu./acre loss at a cost of $66/acre.

N-decision model boosts savings

Frank Moore, an independent agronomist who farms about 2,000 acres in Howard County in northeast Iowa and southeast Minnesota, has been testing Cornell University’s online nitrogen management tool, Adapt-N. The popular program uses a computer model, high-resolution weather information and grower information on soils, crops and management to more precisely assess how much N is needed at sidedress time, among other things.

Moore ran a couple of scenarios in mid-June on a Minnesota farm he operates to compare the quick and easy Minnesota N-decision tool to recommendations from Adapt-N.

“The first scenario was for a Minnesota farm I operate where 140 pounds/acre of anhydrous ammonia was fall-applied on corn following soybeans. The Minnesota tool called for 40 to 70 pounds of additional N, while Adapt-N suggested 100 pounds,” Moore says.

In a second comparison, with everything the same except spring-applied anhydrous, the quick and easy Minnesota tool called for 40 to 70 pounds of additional N again and Adapt N recommended 45 pounds.

“The Minnesota tool has some limitations—the 40 to 70 pounds spread can represent a significant range in cost over a lot of acres—but I would encourage people to use it,” Moore says after his quick comparison. “Using it helps create an awareness of how nitrogen management and weather are closely linked. It helps reinforce the thoughts that the earlier you apply N and the wetter the spring is, the more likely N will be lost. And lost N is reflected in how the crop looks. Using this tool with Adapt-N might also lead people to discover how Adapt-N (find it online at http://adapt-n.cals.cornell.edu) can further refine their nitrogen rates.”

Fall N application advice

The University of Missouri, like most who make N recommendations, says the BMP of timing for N fertilizer applications is to apply fertilizer as close as possible to the period of rapid crop uptake. Fall N application is considered relatively high risk and is not a BMP. For those who are willing to take the risk in order to apply N at a lower cost and without interfering with spring field work, the University of Missouri Extension recommends:

Use only anhydrous ammonia—it converts to nitrate more slowly than any other form.

Use a stabilizer.

Apply N on no more than half—preferably only one-quarter—of planned corn acres to limit your risk.

Delay application of anhydrous ammonia until the soil temperature at a 6-inch depth reaches 50 degrees

The risk of N loss increases the farther south you farm in Missouri

High-pH soils are more likely to lose fall-applied N, don’t fall-apply N on them.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like