With the coming of age of different chemistries in the soybean seed market, off-target drift has been an increasing concern for producers employing the new chemistries. Enlist E3 soybeans were available for planting in 2019, but 2020 is the first planting season where these 2,4-D-tolerant soybeans are available to farmers in commercial quantities.

With the acreage of E3 soybeans set to dramatically increase across the soybean belt, there is no doubt that off-target drift will be a continued concern for some farmers on their non-2,4-D-tolerant soybean fields.

A University of Nebraska field study that began in 2019, and will continue through this growing season, is looking at the effect of microrates, or drift rates, of 2,4-D on four soybean types — including dicamba-tolerant, Roundup Ready, LibertyLink and conventional.

Stevan Knezevic, Nebraska Extension weed scientist, recently explained the differences between dicamba and 2,4-D and the microrates of each at a Crop Production Clinic in Norfolk. He explained some of the differences between dicamba and 2,4-D impacts from off-target microrates on nontolerant soybeans.

"We've been using dicamba and 2,4-D for 30-plus years," Knezevic said. "But with the introduction of dicamba- and 2,4-D-tolerant varieties coming to market, we are using those more and more."

Study results

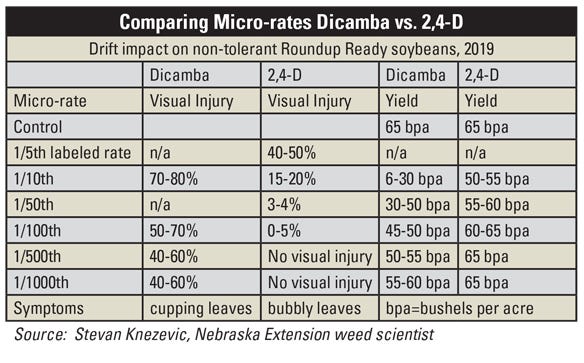

Studying and comparing using both a visual assessment and actual yield differences (see table below) after the application of various microrates that simulate drift in the field, Knezevic talked about some of the early findings.

One-tenth of the labeled rate of dicamba caused 70% to 80% plant damage according to trained visual assessment, he said. The same proportional microrate — one-tenth the labeled rate — caused 15% to 20% visual damage from 2,4-D application. Yields from this same proportional microrate on dicamba ranged from 6 to 30 bushels per acre. The 2,4-D plot yielded 50 to 55 bushels from one-tenth the labeled rate.

The same trend continued as the microrates became more diluted. One-hundredth of the labeled rate produced 50% to 70% visual injury from dicamba, while the same proportion of the labeled rate of 2,4-D exhibited 0% to 5% visual damage.

On the yield side, this microrate produced 45-50 bushels per acre in yield on the dicamba plot, but 60-65 bushels per acre on the 2,4-D plot. The control plots yielded 65 bushels per acre as well. With a microrate of one-thousandth of the labeled rate, visual damage was 40% to 60% on the dicamba plot, and yields were 55-60 bushels per acre. The same microrate on the 2,4-D plot left no visual damage and yields the same as the control.

Looking at differences

Symptoms of off-target drift and microrates are different for each type of herbicide. "Dicamba boosts the growth in the plants, and that's why you see the curling and twisting of the plants," Knezevic said.

Usually, two days after application, there will be initial leaf cupping in nontolerant plants from dicamba. Glyphosate is different, in that it takes four to seven days to show symptoms, depending on the temperature, and leaves will turn yellow. With 2,4-D, off-target soybean plant damage will consist of what Knezevic calls "bubbly leaves," and will take between seven to 10 days to exhibit those symptoms.

LEAF CUPPING: Dicamba microrate injury results in a cupping effect on soybean leaves.

"Volatility is much higher with dicamba," he said. "It is not as much with 2,4-D, and very little with glyphosate." Higher temperatures increase volatility. "Dicamba is also rainfast in four to six hours, while glyphosate is rainfast in about an hour, and rainfast for 2,4-D is varied," he added.

For successful use of any type of herbicide, weed height at the time of application is generally important. "We've been using glyphosate for 20 years, and it still works as long as you don't have resistant weeds," Knezevic said. "However, with dicamba and 2,4-D, bigger weeds will be crippled, but they will curl back and start growing again."

The same goes with application rates. Producers can't cut the application rate with dicamba and 2,4-D if they expect to get a good kill on weeds. This fact makes sprayer calibration even more important with these herbicides.

Of the different types of soybean seed tested in studies, dicamba-tolerant seemed to be the most tolerant of microrate off-target application, while conventional soybean varieties were the most sensitive, Knezevic said. The study also is testing the effect of microrate applications at different growth stages in the plants.

Learn more by visiting cropwatch.unl.edu or by emailing Knezevic at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like