February 23, 2017

By Emerson Nafziger, University of Illinois

The unseasonably warm and dry weather we have had during February this year has a lot of people applying ammonia, and others considering it. This raises the question of whether or not February is a good time to apply NH3, and also the question about whether or not a nitrification inhibitor (N-Serve) should be included in late-winter applications.

We encourage waiting until soil temperatures are below 50 degrees before making NH3 applications in the fall, and then to use N-Serve to slow conversion of ammonium to nitrate. Although it was several days into November before soil temperatures fell to 50 last fall, most people were patient, and NH3 went on well. We have not had as much wet weather since then that we had in December 2015, but the soil was not frozen for very long in recent months, and tiles lines have been running for some time in most areas.

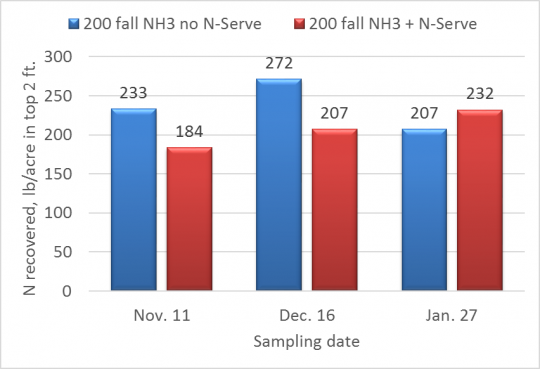

Along with Dan Schaefer of IFCA, we are working on an N-tracking study funded by the Illinois Nutrient Research & Education Council (NREC) that includes three on-farm sites in central Illinois. We applied 200 lb. N as anhydrous ammonia in late October last fall, both with and without N-Serve. Figure 1 shows the amount of N (ammonium plus nitrate) that we have measured in samples taken in November, December, and late January. These are averages across the three on-farm sites.

Soil N recovered following application of 200 lb. N as NH3 in fall 2016. Data are averages over 3 on-farm sites in central Illinois.

Nitrogen in February? | The Bulletin: Pest Management and Crop Development Information for Illinois

The variability over time that we see in Figure 1 is normal with such sampling; we can’t say with confidence that amounts recovered changed over sampling dates or with N-Serve. When we recover amounts of N close to the amounts applied like this, we take that as an indication that there hasn’t been a lot of loss of N to date. In fact, we recovered considerably less N in February 2016 than we had applied in fall 2015, but by April we were able to recover the amount we had applied, and by May, after mineralization had kicked in, we recovered more N than we had applied the previous fall.

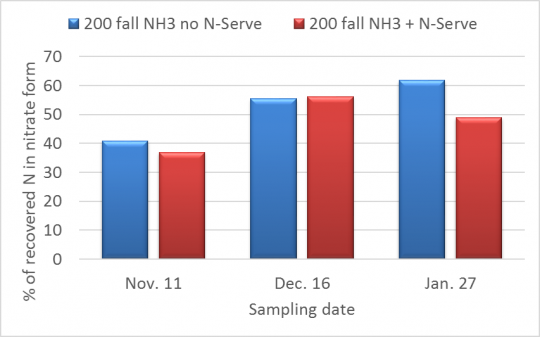

The percentage of soil N present in the nitrate form is also important, especially this far in advance of crop uptake. As a negatively charged ion, nitrate is not held by the soil, and so it will move freely with water as water moves through the soil, including into tile lines. Figure 2 shows the percentage of the N amounts shown in Figure 1 that was recovered as nitrate. Like soil N, percentage nitrate is not a very precise number, but we can see that nitrate percentages have gone up some since the fall but do not seem to be changing very quickly, and that N-Serve might be slowing this conversion to a small degree. At the same time, with more than half of the N now in nitrate form, and with soil temperatures above normal now, it is likely that most of the fall-applied N will be nitrate by May, if not earlier.

Nitrogen in February? | The Bulletin: Pest Management and Crop Development Information for Illinois

Figure 2. Percentage of recovered N (from Figure 1) that was recovered in the nitrate form.

Nitrogen in February? | The Bulletin: Pest Management and Crop Development Information for Illinois

Does this mean we should hold off applying if soil temperatures rise to the upper 40s or lower 50s in February? If soil conditions are good, I don’t see a good reason to wait. For those who prefer to wait, soils dry now means a better chance of being able to apply NH3 with good soil conditions later in the spring. Nitrogen applied as NH3 converts to ammonium quickly, and ammonium will stay in the soil where it was applied. Nitrification (conversion of ammonium to nitrate) is a biological process, and while its rate is low when soil temperatures are in the 40s, it is not zero. So the earlier we apply NH3, the greater the chance that it will be converted to nitrate by the time soils warm and the crop is growing in the spring. Using N-Serve will slow this conversion, and is likely to be as effective used with NH3 applied in February or March as it is when used with fall-applied NH3.

Whether or not the conversion of ammonium to nitrate is a negative depends on the amount of rain that falls between the time nitrate forms (which depends on time and soil temperatures following application) and when crop uptake of N starts in early June. In the spring of 2016, nearly all of the fall-applied N was nitrate by early May, while very little of the N following spring application of NH3 was nitrate; but without loss conditions, the N from both treatments was fully available to the crop in June. We did not see excessive loss of N in the spring of 2015, even though June was much wetter than normal. That’s in part due to the fact that May 2015 was not wetter than normal, so the N was there in early June, and the crop was able to take it up before it was lost. If we happen to get wet weather in April or May, there could be substantial loss of nitrate, whether we applied it last fall or we wait until April to apply.

You May Also Like