The money farmers have contributed through the Ohio soybean checkoff has expanded the use of soy-based products by supporting product development research. But money is not the only thing companies need to introduce new products based on soy.

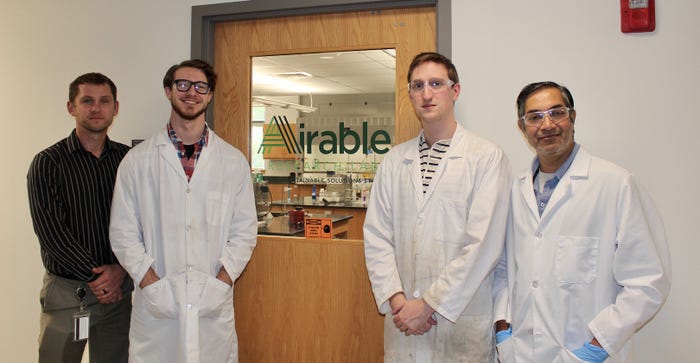

“They need ideas,” explains Barry McGraw, director of product development for the Ohio Soybean Council (OSC) and founder of the new Airable Research Lab. Through the lab, OSC will be playing a more direct role in the research and development process, instead of simply investing in projects done by other companies or research institutions.

OSC has been sponsoring soybean research for nearly 25 years and has seen great success with research partners, such as Battelle, in creating and improving soybean-based products. Going forward, OSC will continue to work with outside research partners, while the new labs will focus research on soybean technology in commercial products, McGraw says. Bringing those products to market will help increase demand for soybeans.

McGraw is a former Battelle program manager. He has been working as OSC’s director of product development and commercialization for the last six years. Over the last year, he’s been overseeing the establishment of the Airable lab, which is housed at Ohio Wesleyan University in Delaware, Ohio.

The name Airable came out of a brainstorming session involving researchers and OSC board members. It refers to both the arable land where soybeans are grown, and the improved air quality that results from replacing petroleum products with soy-based products.

Airable researchers will focus on product development, with the goal of bringing products to market quickly. Taking control of the research will help minimize research expenses and streamline the process, because researchers focus solely on soy products. For most research projects, researchers will be working directly with companies to improve existing products by using soy-based materials. “We want companies to tell us what they want,” McGraw explains.

Long-range vision

In addition, about 30% of the work at the lab will be devoted to “blue sky” projects that look toward future needs. For instance, Airable researchers will be looking at chemicals on the U.S. EPA’s hit list, because companies will be looking for replacements for those chemicals as they are banned.

Researchers can also get clues about future needs from restrictions of certain products in California and European markets. For instance, soy-based plasticizers are already being used to replace phthalates that can leach out of plastics and cause health concerns, McGraw notes. “We’re looking for the next material that’s problematic.”

Besides identifying products that fill a need, researchers will be working to make soy-based materials cost-competitive. Generally, that means a soy product needs to be within 10% of the cost of a competing material.

The market will accept a slightly higher cost for a soy product if it is safer or offers environmental benefits, McGraw explains. Companies like to use soy materials when their products can qualify for the USDA’s BioPreferred program or the EPA’s Safer Choice program, he points out.

Soy-based products can also offer improved functionality. For instance, research funded by OSC helped a South Carolina company develop a floor polyurethane that cures more slowly, which makes the floor more scratch-resistant.

Commercial success

Roof Maxx is another example of an OSC-sponsored product that has achieved commercial success. Several years ago, McGraw made a connection with Mike and Todd Feazel, founders of Roof Maxx Technologies, when he was looking for a way to revive the roof on his own house before selling it.

The Feazels were already working with a soy-based product for restoring asphalt roofs, but needed some help with reformulation and scaling up production. Funding from OSC helped them bring the Roof Maxx treatment to a broader market.

Now, Airable Lab researchers are working to develop an improved roof coating with fungicidal properties, to keep roofs looking new longer. The researchers are also looking for flame-retardant properties, which could increase demand for the roof coating, particularly in areas of the country prone to wildfires.

The Feazel brothers had operated their own roofing business for 25 years. They sold the business in 2013 to start a new business focused on making roofs last longer.

Their research turned up a roof coating product that had been patented 15 years earlier, but had never been widely used, Mike Feazel explains. “Ultimately, I drove out to Maryland and I bought out everything they had stored in the corner of a warehouse.”

That soy-based roof treatment formed the basis for the Feazel brothers’ new roofing restoration franchise business. The spray-on product uses bio-based chemicals to replace the petrochemical oils that evaporate over time, explains Feazel says. Roofs age at different rates depending on their location; but in southern Ohio, roofs typically start to shed granules at about Year 10. Applying Roof Maxx readheres the granules and restores the flexibility of the asphalt shingles. Each application costs about 75 cents per square foot and is effective for about five years.

Feazel estimates that about 85% of the home roofs in the U.S. have asphalt shingles. Extending the life of those roofs reduces the waste heading to landfills and saves homeowners money. Already, Roof Maxx has 500 franchise locations around the country. There is no other commercially available roof restoration product on the market, and Roof Maxx is creating a new niche industry that will drive demand for soybeans, Feazel points out. “The market wants it.”

Keck writes from Raymond, Ohio.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like