March 16, 2017

THINK Different.

A ten-year study of tillage and corn-soybean rotations across seven locations in Iowa shows that overall corn yield with a corn-soybean rotation resulted in highest yields across five different tillage systems – compared to corn-corn-soybean rotations or continuous corn.

The long-term study also showed it could be a mistake to base tillage decisions on corn yields only, especially on well-drained soils, if your goal is highest economic return per acre and long term productivity.

--------------

An Iowa State University study of corn and soybean split plots at seven locations from 2003 to 2013 (results just published in 2016) gives a long-term perspective to yields and economic returns from crop rotations and types of tillage.

The study found:

1) There was no detectable increase in corn yields over the ten years.

2) Corn/soybean rotations offered better yield and economic returns than continuous corn.

3) Northern Iowa locations with poorly-drained soils showed higher corn yield penalties for no-till than southern locations with well-drained soils.

4) Soybean yields were similar regardless of tillage system but economic returns from no-till soybeans exceeded conventional tillage.

5) Corn yields and economic returns with no-till and strip till systems on well-drained soils can be competitive with conventional tillage systems.

Corn-soybean rotation rules

“When you factor in all the inputs and costs, you see the highest net returns from a corn-soybean rotation, and the lowest returns from continuous corn,” says Dr. Mahdi Al-Kaisi, a professor of soil management and environment in the agronomy department at ISU.

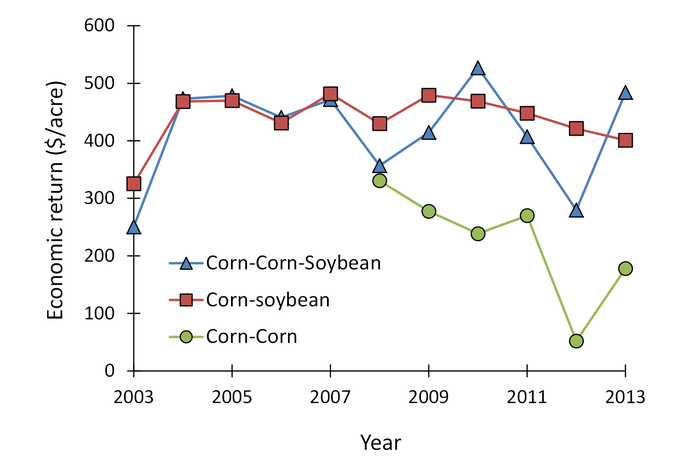

“For ten years, on all tillage systems, you see a corn yield drag of 11% to 28% on continuous corn compared to a corn-soybean rotation. Across all locations, the average economic return per acre for corn-soybean rotations ($388) was 14% higher than corn-corn-soybean rotations ($333) and 41% higher than continuous corn ($227). At the McNay farm, with poorer soils in south-central Iowa, the economic analysis showed we lost money with continuous corn over the years, regardless of tillage type.”

The seven research locations were on ISU research and demonstration farms near Sutherland (northwest), Kanawha (north central), Nashua (northeast), Crawfordsville (southeast), McNay (south central), Armstrong (southwest) and Ames (central) Iowa.

For ten years, on all tillage systems, research showerd a corn yield drag of 11% to 28% on continuous corn compared to a corn-soybean rotation. Across all locations, the average economic return per acre for corn-soybean rotations (workspace://SpacesStore/e37dc097-ff3c-4fd0-9f79-33314ca0e5cc88) was 14% higher than corn-corn-soybean rotations (workspace://SpacesStore/e37dc097-ff3c-4fd0-9f79-33314ca0e5cc33) and 41% higher than continuous corn (Courtesy of Iowa State University27). Land rental cost was not included in calculating economic return, as this was the same across locations.

Yields vary by geography

While the corn-soybean rotation was the best system for economic returns, the research showed considerable variation between the locations, ranging from a $153/acre average return at McNay to an average return of $485/acre at Nashua. Corn yields varied from 108 bushels/acre at McNay to 204 bushels/acre at Nashua. Over all, year-to-year variability of corn yields was 28% across all tillage types, rotations and locations.

Soybean yields varied from 22 bushels/acre to 74 bushels/acre. “Soil drainage, soil temperature, residue breakdown, organic matter mineralization, precipitation and weed pressure in a wet season are all factors for regional variations in yields,” Al-Kaisi says.

“There was no detectable yield trends for either corn or soybeans over the ten years of study,” he says. “We did find that soybean yields were maximized at some locations in years with less precipitation in May, cooler summer temperatures and higher precipitation in August.” The study also showed that soybean yields were 5% higher and economic return was 9-11% higher after two years of corn in a corn-corn-soybean rotation compared to those in a corn-soybean rotation at five of the seven locations.

Tillage costs, soil degraded

The five tillage systems—no-tillage (NT), strip-tillage (ST), chisel plow (CP), deep rip (DR) and moldboard plow (MP)—were randomly assigned as main plot treatments. The same tillage operations for each tillage treatment were conducted every fall at each location for the duration of the 10-year study. No-till was the typical no pre-plant disturbance of the soil, other than use of a single coulter and residue cleaners. The tilled zone in strip till was 8” wide and 6-8” deep. All tillage treatments, except NT and ST received spring field cultivation 6 inches deep prior to planting.

Al-Kaisi says input costs for tillage systems (CP, DR, and MP) were 7.5% and 5.7% higher than those for no-till and till-plant, respectively, across the board for all locations and all rotations. Despite lower input costs, the economic return for the no-till system in a corn/soybean rotation was generally lower than that for the tillage systems and strip till systems, and significantly lower in more than half the locations.

“In the corn-soybean rotation, corn yields with the tillage systems (CP, DR, and MP) weren’t significantly different from strip-till,” Al-Kaisi says. “But corn yields with both the tillage systems and strip-till were significantly higher than no-till at the northern locations with poorly drained soils. No-till yields were more competitive at southern locations with well drained soils.”

Factor in soil health

Al-Kaisi cautions, however, that yields and even economic returns over the ten-year span don’t tell the whole story. “You decimate microbial populations in a continuous corn situation,” he says, “and with tillage in general you deplete soil organic matter. Just three weeks after tillage with a chisel plow, approximately 250 pounds per acre of organic carbon can be lost. In contrast, organic matter is less vulnerable to loss in a corn-soybean rotation with a no-till system.”

“You should expect to pay more to rent soils with high organic matter,” Al-Kaisi says. “More than half your yield (56%) depends on the organic matter in your soil. Much of the reason for that is that water holding capacity increases with more organic matter. It’s significant to build organic matter and soil conditions over time with no-till.”

Check out the study here: http://bit.ly/10yeartillage

About the study

The objectives of the Iowa study:

1) investigate the seasonal variability of corn and soybean yields as affected by five tillage systems and three crop rotations and their interactions at each of seven locations.

2) identify appropriate tillage systems for each crop rotation and location by evaluating criteria such as yield and economic returns.

3) evaluate the rotation effect on corn and soybean yields and economic returns at each location.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like