December 12, 2019

By Bruce MacKellar and Roger Betz

What is the potential for corn to dry in the field over the winter months? In all honesty, not particularly good on a per-day basis during the December-to-February time frame.

However, there are a lot of days during this period, and even small amounts of drying per day can lead to much lower moisture levels by early spring. With corn moisture levels remaining above 30% in many June-planted cornfields, the cost of drying corn this fall is going to be very high. When considering the options, producers need to balance the risk of yield losses from leaving corn in the field with the cost of drying the corn.

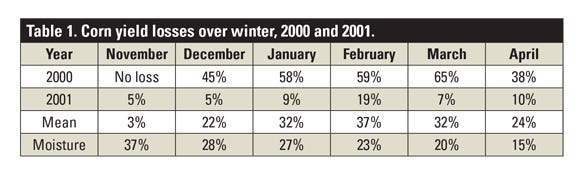

Joe Lauer, University of Wisconsin Corn Extension specialist, conducted a study looking at corn yield losses over winter during 2000 and 2001. The results are in Table 1.

Yields shown in Table 1 reflect the percent of harvest loss by month. In 2000, there was heavy snowfall, which affected how much corn the combine was able to get into the machine. In 2001, there was much less snow, and hence, less overall losses.

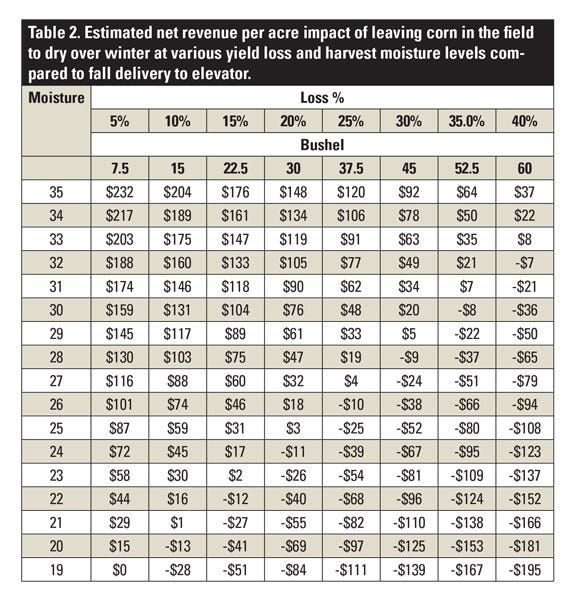

A partial budget analysis investigated the net revenue-per-acre impact of leaving 150 wet bushels-per-acre (30% moisture) corn in the field overwinter to dry to 18% moisture compared to taking this corn to an elevator to dry.

The results showed that corn at 30% moisture left to field dry, with a 30% expected yield loss, still would have a $20 per acre advantage over drying the crop this fall. This assumes there will not be substantial loss of grain quality over the period that the corn remains in the field.

The table below provides the breakeven for various corn moisture levels in the fall and expected yield loss from field drying.

The values in Table 2 were calculated using 150 bushels-per-acre wet bushel yield that had a test weight of 50. Drying charge was calculated at 4.0 cents per bushel per point of moisture above 15%. A shrink calculation of 1.4% per percent of moisture above 15% was used to calculate the number of marketable bushels. Drying charges, trucking charge for hauling the water in wet corn and a deduction of 5.0 cents per bushel for test weight were calculated on a wet bushel basis.

Factors that can contribute to overwinter yield losses

As you might expect, there are several factors that can contribute to overwinter yield losses, and the risks for loss can be substantial.

Lodging. Corn has the potential to lodge, which can substantially reduce harvestable yield. This is particularly true where stalks have been weakened by tar spot or other leaf diseases or stalk rots. Leaf diseases causing loss of green leaf tissue during the growing season can cause the plants to scavenge carbohydrates from the stalk, reducing stalk strength and increasing the potential for lodging.

Ear size and weight. Heavy ears create more potential for lodging. In addition, activity of insects such as corn borer and, to a lesser extent, western bean cutworm can affect stalk and ear shank strength, causing more lodging and corn ear drop.

Winter weather. No precipitation events are created equal. Wet snow tends to be more problematic than dry snow. Ice storms also can add weight that can increase lodged corn. High wind conditions during any of these events, including wind driven thunderstorm rainfall during the winter, can cause significant lodging.

Wildlife damage. Deer can be a significant factor in making the decision of leaving corn in the field to dry. Overwintering deer can choose to yard up in standing corn as an alternative to woodlands and swamps, causing unacceptable levels of yield loss. The extent of damage that will occur is directly correlated with the numbers of deer in your area. If you expect to have fields you will not harvest until late winter or early spring, contact your local Department of Natural Resources biologist to request extra doe antlerless deer tags this fall and round up hunters to proactively reduce the deer herd in your area.

Producers will need to weigh their anticipated risk for yield loss and make harvest decisions based on their corn moisture, risk of yield loss and drying cost.

MacKellar and Betz write for Michigan State University Extension.

You May Also Like