April 12, 2019

For any country that wants to grow an adequate and stable food supply, some level of irrigation is necessary. Even in the Upper Midwestern U.S., where there is ample rain-fed cropland, we count on irrigated acres to provide stable crop production, especially in drought years. As recently as 1988 and 2012, corn and soybean yields in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana tanked, because of droughts. The U.S. food supply would have been on unstable ground in those years, without the irrigated areas in the Great Plains.

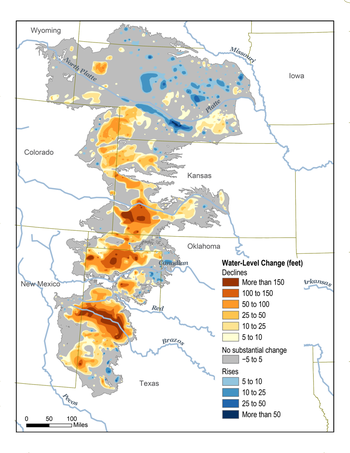

The Ogallala Aquifer, underlying eight states in the Great Plains, supports nearly one-fifth of the wheat, corn, cotton and cattle produced in the United States. However, it is widely reported that water from the Ogallala Aquifer is being extracted faster than it is being replenished in some areas. Because it is a non-renewable resource, the Ogallala Aquifer, and others like it, should be conserved.

The Ogallala Aquifer, underlying eight states in the Great Plains, supports nearly one-fifth of the wheat, corn, cotton and cattle produced in the United States. However, it is widely reported that water from the Ogallala Aquifer is being extracted faster than it is being replenished in some areas. Because it is a non-renewable resource, the Ogallala Aquifer, and others like it, should be conserved.

It is possible to conserve these important nonrenewable water resources, like the Ogallala Aquifer, and still protect the U.S. food supply in drought years, by irrigating the Upper Midwest. While this may seem like an irrational idea and waste of resources, let’s take a closer look at how it could be accomplished.

The Upper Midwest often receives excess rainfall, resulting in flooding of high value metropolitan areas. In fact, in most years, flood events are more prevalent than droughts. To mitigate flooding, cities often look upstream to locate and build structures to store excess water and reduce flooding. In times of drought, the same water retention structures could become the water source for drought-stricken cropland. This seems like an excellent way to build a more resilient landscape; capturing water during periods of excess and using it in times of need.

Multiple revenue streams could be used to finance the dual-purpose water retention structures. Those farmers interested in spending money on irrigation systems, coupled with reductions in federal crop damage premiums, could offset the cost of the impoundments. Downstream, the beneficiaries of improved flood control could also help pay for a percentage of water retention structures.

In 2012, Jim Sladek, a southeast Iowa farmer, said his irrigated acres out-yielded his non-irrigated areas by 120 bushels per acre; the profits of which paid for the original irrigation system – in just one year. In 2014, Sladek built an 18-acre pond for another irrigation system. Jim is still making adjustments, but he is confident he can increase yields by 50 bushels/acre/year, on average.

Sladek says, the harder farmers push to produce more, the higher the risk of something going wrong. Irrigation is one input that should improve yields and lower risk. There are few inputs, other than water, that can make this claim. For this reason, he is excited about irrigation in the Upper Midwest.

As an alternative to pumping nonrenewable resources dry like the Ogallala Aquifer, why would we not consider using water from flood retention structures to irrigate Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana?

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like