Traders watching USDA for clues about the direction of corn prices return their focus, briefly at least, back to old crop data with the April 11 update of World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates.

These monthly numbers won’t include any guesses about 2023 production or usage, but will instead show how the government interprets recent data on grain stocks and usage. Big changes aren’t expected to the bottom line of projected supplies left over at the end of the 2022 crop marketing year on Aug. 31.

Attention from futures price swings should return quickly to weather after a slow start to planting, amid lingering concerns about the impact of drought in the western half of the growing region.

While watching new crop bids for preharvest pricing opportunities is important, farmers still have a whole lot of inventory to move – 4.1 billion bushels of it, according to USDA’s recent estimate of March 1 supplies. That grain represents around 30% of the 2022 corn crop, smack on the average over the past decade or so. In all, 7.4 billion bushels were sitting in on-farm and commercial storage. On-farm bins held 55% of March 1 inventories, in the middle of the 49% to 60% range seen in recent years.

While many market participants will be watching weather reports and the daily export wire for sales, the often-overlook stocks data could hold clues for growers wondering if it’s time to fish or cut bait on their remaining inventory. Interpreting what the numbers say about potential may in part depend on where that grain is located.

Cash vs. futures

Taking a tip from the grain merchandisers on the buy side of the trade could also pay off. That’s because elevators are interested in basis, the difference between cash and futures.

Average U.S. cash prices are down around 11% since harvest in mid-October. From that standpoint, storage will need a big rally to pay off on the 2022 crop.

But for some of those hedging basis, storage returned dividends. Selling futures at harvest protected inventory from falling prices, positions that benefited as the difference between cash and futures prices strengthened.

The unusual nature of the 2022 growing season helps explain some of the wide variance in basis patterns around the Midwest. While total U.S corn production was 1.4% below its 10-year average, state-by-state results ranged from boom to bust. Growers in the central and eastern Corn Belt generally harvested decent crops. But the west was a disaster. Nebraska corn production fell 13% below average while Kansas harvested only 80% of a normal crop.

Mid-October corn bids reflected those results. Harvest basis across the Midwest is generally negative on average. That was also the case last fall outside the parched West. But cash prices in Central Kansas averaged more than $1 more than nearby futures. Central Nebraska and Central Missouri also saw positive basis.

Some hedgers lose

The Kansas cash market last week ended with basis that was still much stronger than average. But nearby bids averaged “only” 55 cents more than futures, a decline of nearly 50 cents from mid-October. Hedgers lost as a result – the red-hot bids last fall were a flashing red light to move corn early because the market wanted it so badly.

Fast forward to last week and that demand urgency had shifted. Bids in Iowa and Illinois, which as usual produced a third of the entire U.S. crop, were running around 20 cents over the board, a remarkable turnaround. End users who didn’t want to buy Iowa corn in October paid dearly for it in April, at least as far as basis is concerned.

Not every place saw better than average spring bids. Bids in Indiana and Ohio last week were weaker than normal, due to all the corn in Illinois and Iowa standing between eastern growers and the short crops in the west, though their harvest to April appreciation was still above average.

Stocks clues

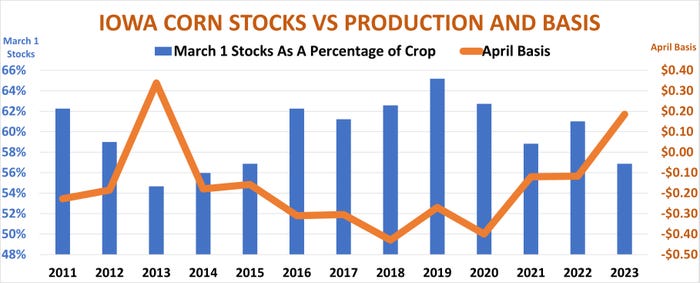

USDA’s recent tally of March stocks helps explain some of what happened. Iowa’s March 1 corn inventory as a percentage of the state’s crop explains almost 60% of the variance in April North Central Iowa basis. Basis there tends to be stronger when that percentage is lower than the previous year. That’s what happened after the drought crop of 2012 and again last year.

Look out Cleveland

So what, if anything, do stocks reveal about potential for basis gains through the end of May? On average, locations in the eight states studied saw appreciation of a dime or better during this period.

Now, there’s an adage in the market that attributes basis strengthening to grain being in “strong hands” – that is, owned by commercial hedgers. But basis out in the country tends to strengthen in spring when it’s under farmer control and likely unhedged. This year’s farmer ownership is about average, which could increase chances for average gains.

Still, the drivers of appreciation in Illinois and Iowa could be different from forces affecting other states.

Illinois and Iowa March 1 stocks compared to the size of the state’s crop tends to have a negative correlation to basis appreciation. That is, basis in both of these “I” states tends to improve when their March 1 stocks’ share of production is tighter than normal, which it is this year, though the relationship is not terribly strong.

By contrast, basis in western states like Nebraska and Kansas tends to improve from April to June when their state has a higher share of U.S. stocks, as it does this year.

This factor could punish appreciation in the eastern Corn Belt. Indiana and Ohio tend to have a negative correlation to their stare of U.S. stocks. When it’s bigger than average, as it is now, basis tends to weaken in the spring.

Most farmers don’t hedge inventory with futures, storing for flat price gains. But basis changes can make a good futures market better – or a bad one worse, and vice versa. Some growers may be better off moving cash now and buying futures – a basis contract – or replacing inventory with calls if they’re still bullish on the board.

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like