Battered grain markets finally showed signs of trying to bottom last week. But without a swift recovery of bullish sentiment, growers who held off selling the best new crop corn and soybean prices in a decade may be headed for a familiar marketing strategy this fall: holding and hoping.

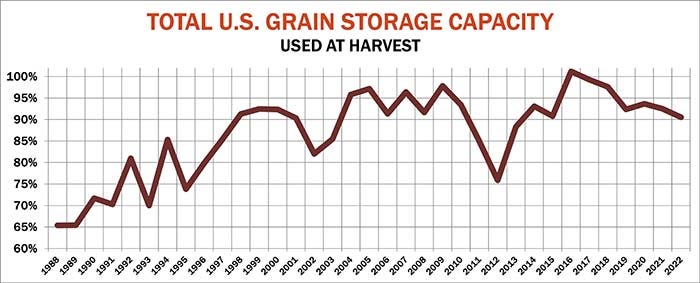

The good news for farmers with unpriced production: Even with blockbuster yields plenty of storage space should be available at harvest for those betting on better days ahead. And if yields come in only slightly less than expected, the percentage of storage capacity used nationwide for row crops could fall to its lowest level since bins refilled following the 2012 drought.

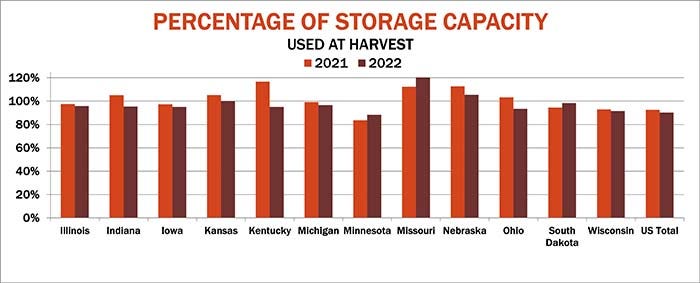

To be sure, those without enough on-farm space could wind up dumping in ground piles at elevators, if fields in their area are more bountiful than average. Still, even some states lacking capacity in recent years could see more favorable conditions -- as long as transportation bottlenecks and weather don’t compromise a steady flow in and out of commercial facilities.

Missouri and Nebraska could face more grain stocks than bin space from 2022 production and supplies left over from 2021. But both states have faced this situation before. And if cash bids in those locations fall too far below other areas, that grain could be sucked into the pipeline more quickly to alleviate some of the crunch.

New crop basis trends so far this summer generally reflect prospects elevators face locally. Buyers posted weaker than average bids at some locations in Nebraska, with fall soybean and some corn basis fading in along the Mississippi River in Iowa and Minnesota. But while North Central Iowa basis weakened, markets in Minneapolis firmed a little. To the east, eastern Corn Belt buyers started to strengthen their boards as more storage space appears to be available there.

Storage conditions aren’t the only factor in basis decisions elevators face this fall as the industry battles market volatility, inflation and fears of a global recession. Demand remains uncertain though world food prices eased again in June. Higher interest rates only add to the tab for storing grain, whether you’re an international grain company or a farmer with a few hundred acres, while expensive fuel prices increase the cost of transporting grain to deliverable locations, a factor affecting shippers of every stripe.

Harvest rail bills jumped sharply toward the end of June, though some routes are still a third off highs for the slot set earlier this spring despite fuel surcharges that swelled to all-time highs. The trend for river shippers was similar, sending fall levels near or above 2021 as tows continue to face labor shortages , exacerbating delays. Low water levels on the river system also forced tows to cut volumes to accommodate lower drafts.

Moving grain by truck remains expensive, driven by on-highway diesel bills near record highs around 75% more than a year ago.

Cheaper freight could give buyers more leeway to strengthen bids, especially if farmers hold tight. Otherwise those charges could be passed on to farmers in the form of weaker basis.

Another factor could also be in play this year. Lack of carry in the futures markets may limit how much elevators can push basis and still make money.

In this case, carry is the spread between harvest futures and contracts for deferred delivery in 2023. Elevators buying from farmers traditionally can’t speculate on flat prices going up or down. Rather, they typically hedge purchases in futures to capture appreciation as basis narrows. Lack of carry reduces those potential gains unless basis strengthens enough, which happened when nearby futures traded for premiums to deffereds, signaling end users wanted grain immediately thanks to strong exports and domestic usage.

The combination of harvest basis and carry was quite small for corn in the fall of 2021. Elevator hedges worked anyway after nearby basis vs July strengthened around 40 cents by the end of February.

Fearing they won’t get the same boost from demand this year, elevators may weaken bids to make up some of the shortfall because carry is lacking. The December 2022-July 2023 corn spread traded at just 6 cents last week, not even enough to pay for one month of full commercial carry, which is now running around 10 cents a month.

Carry in the soybean market is rarely enough to pay for long-term commercial storage at deliverable locations. That’s even more the case this year, with the cost of full carry around 13 cents. While November traded last week at a five-cent discount to January, the harvest delivery contract was premium to other 2023 delivery months.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like