Trees are just a part of most farmsteads or ranches. Many rural properties, even in the Plains states, include riparian woodlands, groves and old stand timber.

That’s why landowners often ask themselves if they might have marketable timber on their farms that could offer an additional income stream, if managed properly. But how do you know if you have something that is of value?

What is the market?

In the Plains states, walnut, oak and maple are among the most common marketable species.

“Harvesting trees as part of the management of the forest presents more volume and sustainable wood products when done correctly,” says Kim Slezak, Nebraska Forest Service forest products specialist. “Very little Plains states’ trees will ever be construction-grade lumber, as there are mostly hardwoods.”

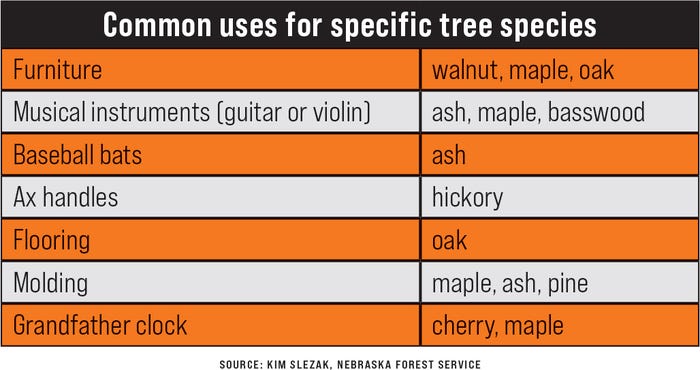

But these can be useful for furniture, molding, flooring and other uses (see table).

“If you are managing your property and want to keep the woodlot healthy and functioning, a harvest of marketable timber can help pay for the management,” Slezak says. “Species and quality do play a part in that, so just because Dad or Grandpa planted walnut for the future, if the stand has not been pruned and thinned, it is likely not growing to its full potential or top quality.”

Landowners can advertise their marketable trees, listing species and sizes on websites or wood product newsletters, which often come out regularly and list available standing timber for sale, Slezak says.

When to ask a forester

Slezak says that if you receive a lump sum or “by-the-piece” offer from a logger, marketer or processor, “it’s always good to get a second bid, and a forester can provide a volume estimate to judge if you are getting a good value for the material.”

But what about those trees that are deep into the woods and on rough terrain? “The farther the trees are from semitruck and trailer access, the more forwarding from landings to loading a log truck,” Slezak says. “It comes down to more expense.”

Farmers probably prefer allowing access to woodlots for loggers after grain harvest or before planting in the spring, and working on frozen ground is most likely preferred to prevent soil compaction, she adds.

After the trees have been harvested and loaded, the site may be a bit messy, Slezak explains.

“Part of your contract with the logger can specify how much material or slash, like tops and branches, are left in the woods to decay and build soil, or left on the landing to help reduce erosion,” she adds.

Slezak points out that marketable trees do not have to be located in a woodlot. “Trees in yards, city or rural, in parks and along streets can often be utilized as lumber,” she says.

Learn more by contacting your local or state forestry agency. Email Slezak at [email protected].

Read more about:

ForestAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like