Farmers looking for expenses to prepay by the end of the year have plenty of choices for their annual attempt to minimize taxable income. Early discounts provide an incentive for some purchases like seeds, while fertilizer could eat up a quarter of a grower’s budget for 2023 corn.

Costs for energy, by contrast, account for just 5% or less of projected crop expenses, according to the latest estimates from USDA. But timely purchases are never out of season, and locking in fuel for next year could offer protection against petroleum markets that, last week, fell by a third from highs set March after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Tax deadlines aren’t the only reason for urgency. Energy is notoriously unpredictable – one reason its volatility index, or VIX, is double levels seen in the stock or grain markets – and risk appears to be increasing.

Seasonal factors in the fuel market are another motivation to consider action soon: Diesel tends to be cheapest in early winter because farmers aren’t burning as much as they do during spring planting or fall harvest. Even more incentive comes from an international market still reeling from effects of the Ukraine invasion and Covid pandemic.

Still cheap

After trading as low as $73.60 a barrel last week, crude oil futures moved back above $80. That still looks a little cheap according to my model of supply and demand in the sector, which projects a current average price around $86.50. While that target isn’t too far above the market, the range for crude over the next year could be huge, anywhere from $47.50 on the low side to $125 if the market becomes unglued.

Think that spread is too large? Just remember that nearby crude traded from $66.12 to $130.50 over the past 12 months.

OPEC+ is back

The latest inflection point could again come from OPEC and Russia, which continue to discuss whether to add to production cuts that took effect in November. While additional restraints aren’t expected yet, another round of falling prices could increase pressure on the cartel to act.

The OPEC+ decision comes as sanctions against seaborne Russian crude exports are due to ramp up. Plenty of Russian crude has found a home elsewhere, especially in India, but new restrictions could make it more difficult for G7 countries and Europe to obtain cargoes, sending them onto a world market where supplies are already tight.

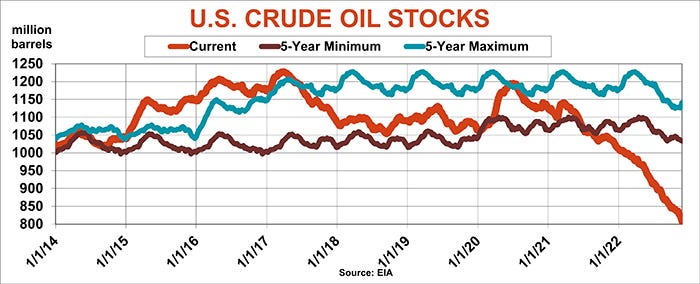

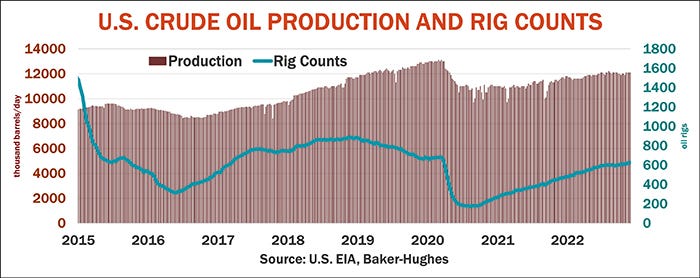

After swelling during Covid lockdowns, total U.S. oil inventories dropped last week to the smallest in more than 20 years as the Strategic Petroleum Reserve was drained near 40-year lows. Those stocks represent a 45-day supply at current refiner usage, 25% less than before the pandemic. U.S. crude production has flatlined after rebounding from pandemic cuts, and stands 7.6% below peaks reached in the fracking boom.

Fuel for flyover country

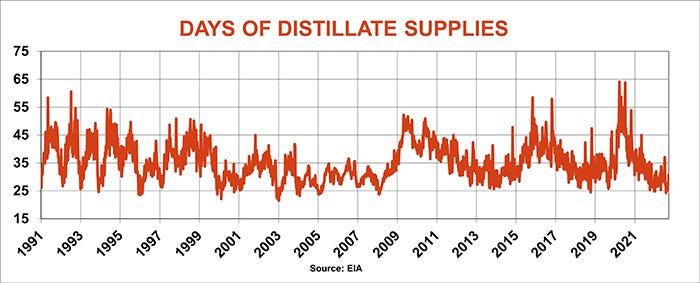

Supplies of distillates, mostly diesel, are the smallest since 2008, when futures first breeched $4 a gallon. After surging briefly past $5 in April, ULSD futures held support above $3 last week.

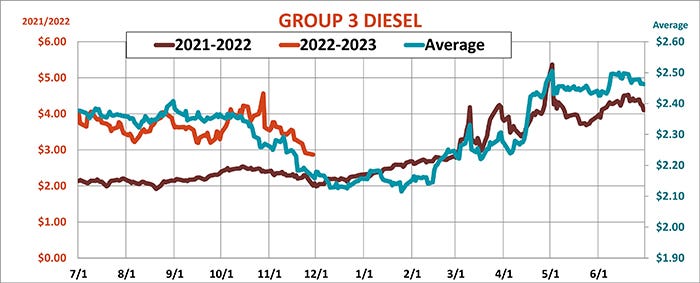

Those contracts are delivered in New York, where the cash market is tightened further during the winter by demand for heating oil. Fuel in flyover country normally trades below futures this time of year, but that that discount is far weaker than normal. Midwest cash wholesale benchmarks are 15 to 35 cents below futures, basis that can create obstacles and opportunities for farmers looking to hedge their needs for the coming year.

The obstacles include basis risk between local cash prices and futures markets that may or may not provide a good hedge. Farmers with adequate on-farm storage don’t have that risk; they can use this opportunity to just fill ‘er up.

On average, the Group 3 benchmark many dealers use tends to stay weak in December before firming as agricultural demand kicks in. But last year the pullback ended in the first week of December, with prices of crude oil and products rising steadily to 20-year highs after OPEC+ announced cuts in October 2021.

This year there’s another wild card: China. Fears that county’s strict Covid policies could depress demand helped trigger the market’s pullback this fall. But unusual protests in the Communist country convinced leaders to begin relaxing the policies, prompting ideas a wider reopening could turn around the energy declines.

Bulls thought they got more ammunition from a speech by Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, who fueled hopes the central bank will slow the rate of its monetary policy tightening when it meets Dec. 13-14. Traders largely dismissed Powell’s assertion that rates may have to stay higher for longer to cool inflation, but there was hopeful news on that front too. Personal Consumption Expenditures, the price barometer watched most closely by the Fed, cooled more than expected in October, though it’s still running at 6% year-on-year.

That optimism was offset Friday by a hot employment report for November, which showed the economy continuing to create more jobs than anticipated.

A bigness problem

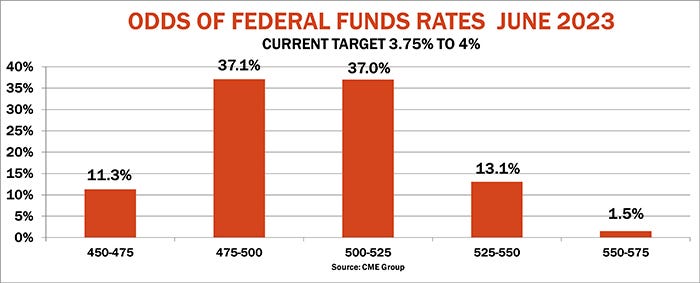

Investors betting on Federal Funds Futures still expect rates to rise another 1% by June 2023, but fewer see this so-called terminal rate much above 5% to 5.25%.

A soft landing for the economy in 2023 or only a mild recession might help energy demand recover sooner than expected. Lower rates also spurred selling in the dollar, which tends to follow the lead of monetary policy. Weaker greenbacks can boost prices for commodities denominated in the dollar, like crude oil and products.

Besides a possible basis trap, ULSD futures have another obvious drawback: they’re big, 42,000 gallons, far more than most operations need. That size could also rule out futures based on the basis between New York futures and cash market benchmarks like the Group 3 price, which are the same size.

Companies with experience trading these markets may be able to devise other swaps contracts suited to an individual grower’s needs, and local fuel dealers may also offer deferred cash contracts for growers without enough on-farm storage.

Another alternative for futures traders could be micro-crude oil futures, contracts one-tenth the size of the normal 1,000-barrel lots. These don’t have the volume of full-size futures, but are more suited to the average farm. Smaller contracts for New York ULSD are also available, though these attract little volume or open interest.

The trouble with using crude oil to hedge fuel is another basis issue. Crude and ULSD contracts are closely correlated over the long haul, but the connections can vary widely short-term. In November the daily one-month correlation ranged from above .9 to less the zero on a scale of -1 to +1.

Propane power

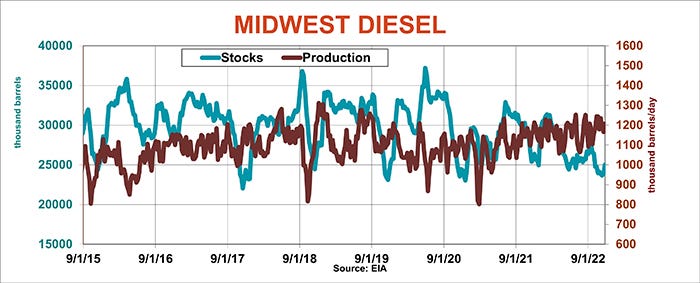

Adding Midwest basis to the mix increases uncertainty. Midwest ULSD production hit a two-year low in November and is slowly recovering, while inventories remain towards the high end of their recent range.

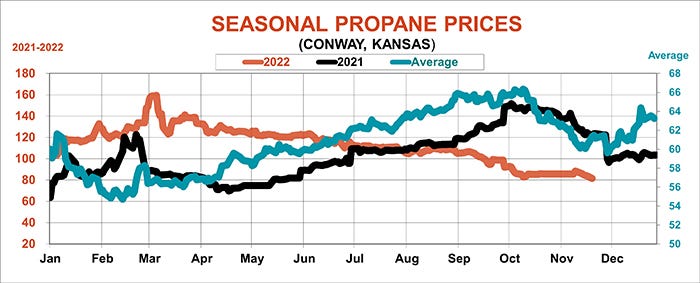

The other segment of many farms’ energy needs is propane, which tends to follow crude oil long-term but has a different seasonal due to its use for winter heating. Typically the best time to refill tanks is at the end of winter or in early spring, but weakness can also extend into summer if economic events pressure financial markets.

Wholesale prices hit their lowest of the year last week as stocks rebuilt before winter, but weather and economics can change the mood quickly. So, following the market can help spot opportunities.

Farmers also have an interest in energy from the income side of the ledger, thanks to the biofuel industry.

Soybean crush margins are down from record highs set earlier this year but remain attractive, though soybeans processed in September and October are behind the pace forecast by USDA for the marketing year. Biofuel mandates announced last week disappointed the trade, causing a selloff in soybean oil, which had benefited from the rebound in crude.

Ethanol margins remain also under pressure, with lackluster gasoline usage cutting demand from blenders.

It’s a lot to chew on, for sure. But tightening profit margins mean every penny counts to keep your bottom line from running out of gas.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

Read more about:

TaxesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like