Chatter in the grain market during March normally obsesses over what USDA’s first survey of planting intentions will show at the end of the month. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine upended that convention for sure. Fears about global grain supplies sent wheat prices to 14-year highs, with nearby corn and soybeans hitting their best levels in nearly a decade.

But acreage concerns still loom large. A market already buffeted by the pandemic and the second year of drought in parts of South America now faces rising fertilizer prices that complicate acreage decisions, increasing prospects for the government’s March 31 Prospective Plantings survey to provide more volatility.

USDA updated the unofficial projection for seedings at its outlook conference Feb. 24-25, calling for farmers to plant 92 million acres of corn, down from 93.4 million in 2021. Soybean plantings would increase to 88 million acres, up from 87.2 million last year.

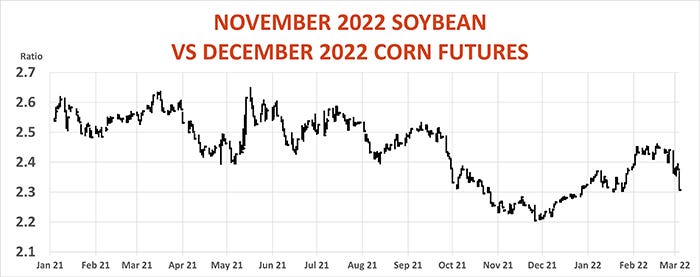

The agency’s estimates were based on economic models, so there’s plenty of room for changes when the voice of farmers is actually heard. Soybeans dominated the discussion this winter due to anticipated yield cuts in Brazil and Argentina that caused November 2022 futures to gain ground against December 2022 corn. But the ratio never strengthened significantly more than its long-term average of about 2.36 to 1 before the tide turned with Russian tanks, putting Ukraine’s huge corn crop in question.

Futures favor corn

South American drought gave new crop soybean futures a bit of a boost to start 2022, but the ratio is starting to tilt toward corn.

Even at current levels the relationship between futures for the two crops isn’t yet screaming “PLANT CORN!” Still, coupled with strong projected profits, USDA’s March corn plantings number could be higher than its outlook estimate, with soybeans losing ground in response.

The government’s National Agricultural Statistics Service normally contacts farmers during the first two weeks of March for its planting intentions report, so changes to futures markets now could still impact the final numbers released at the end of the month. Some other important data points are already decided, though others involving costs are still very much in play.

Traders normally focus on the ratio of new crop soybeans to corn futures in part because it’s easy to track. Farmers are more likely to look at profit per acre differentials between the two crops, a much more difficult calculation to make even in normal times. This year, uncertain fertilizer costs – and availability – are an extreme wild card.

Normally I compare expected profits based on average cost of production forecasts made by USDA’s Economic Research Service. But the latest estimates released by ERS were developed in October, so they failed to account for much of the increase in fertilizer and fuel costs as inflation exploded to 40-year highs. I added $50 an acre for corn and $30 for soybeans, but these are admittedly ballpark estimates.

Russia’s move in Ukraine upended an already gyrating fertilizer market. Even if buyers can figure out how to ship supplies out of the Black Sea and Baltic ports and pay for them in the face of international sanctions, little is likely to move soon. Natural gas is still flowing west from Russia to Europe, but at very high prices, impacting manufacturers’ ability to make nitrogen fertilizers on the continent.

Normally, a lot of nitrogen moves out of Ukraine. Though it accounts for only 2% of world ammonia production, the world’s longest ammonia pipeline provides a Black Sea outlet in Odessa, Ukraine for Russia, which produces 11% of global ammonia. Russia also mines 6% of the world’s phosphate rock – its DAP and UAN exports to the U.S. were already being hit with anti-dumping tariffs.

But potash is the big concern longer term. Not only does Russia produce 20% of the world’s potash, but close ally and sanctions-hit Ukraine neighbor Belarus accounts for another 17% of the total.

After falling from multi-year highs to start 2022, fertilizer prices bounced back when bombs started falling in Ukraine. Urea remains below its fall highs but jumped $250 a ton at the Gulf the past two weeks. Both potash and DAP made new highs this week, and the outlook for ammonia imports was clouded after Yara and Mosaic failed to settle contracts for March at the Gulf.

Getting fertilizer into last-minute position this spring for farmers and dealers who have yet to book supplies won’t be easy, either, thanks to supply chain disruptions and soaring costs for transportation.

Still, both crops appear to pencil out with triple-digit profits for 2022 with corn having the edge on the bottom line.

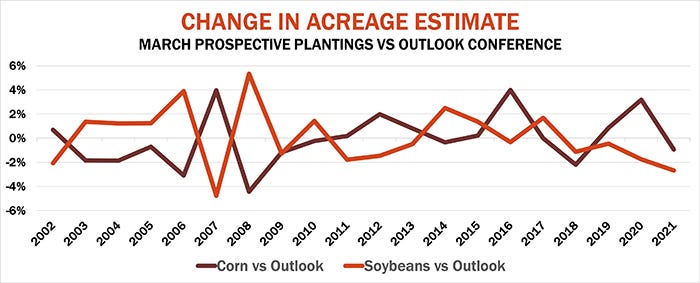

All of these metrics would normally mean USDA’s March ratio of soybean to corn acres could be sharply below the outlook conference estimates, which put soybean acreage at 95.6% of corn. But a huge change from the outlook estimates would be an outlier. Shifts have topped 4% a couple of years, though these occurred during years of extreme price volatility such as 2007 and 2008. The average variation is less than 2% over the past 20 years.

Corn and soybean profit potential

Big changes in estimates from USDA’s February outlook conference to its end of March survey normally occur only in years with very volatile prices, like 2007 and 2008. Could 2022 repeat the pattern?

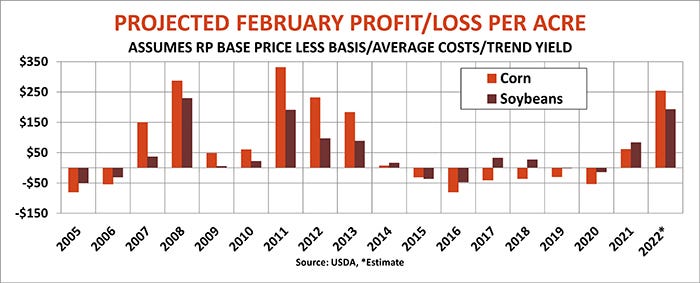

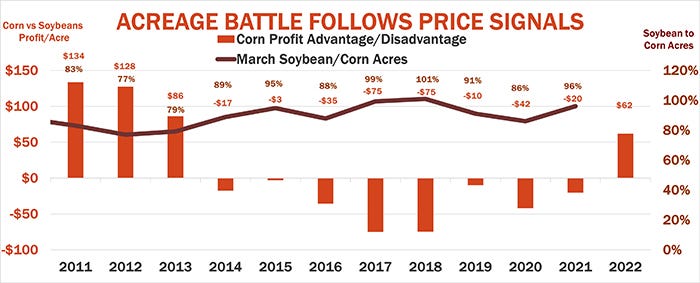

One way I measure profit potential is to look at the price used in popular Revenue Protection crop insurance policies favored by most growers. Based on these prices -- $5.90 for corn and $14.33 for soybeans -- less average basis, corn has a $62 an acre advantage over soybeans.

Soybeans penciled out better than corn last year when prices guaranteed by Revenue Protection crop insurance and normal yields were factored into projections. Corn looks to have the edge this year.

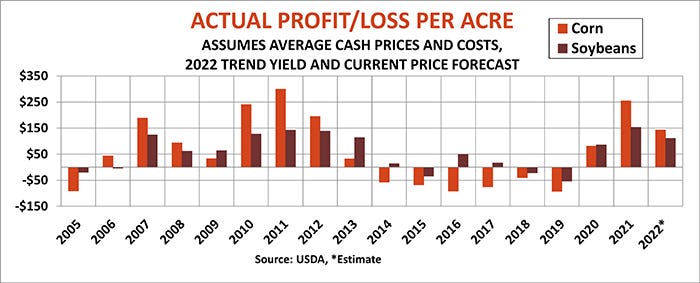

USDA’s outlook conference report provides another yardstick for profits. It forecast the average cash price for 2022 crop corn at $5 a bushel, with soybeans at $12.75. The government’s expectation for normal or “trend” yields – 181 bpa for corn, 51.5 for soybeans – translates into a profit advantage of $31.55 for corn.

Finally, history also suggests farmers also base planting decisions on what they earned for the previous crop – a bird in the hand being worth two in the bush. The marketing year isn’t over, but 2021 crop corn looks to have a $100 per acre profit advantage on soybeans.

Corn has been a decisive winner over soybeans for the 2021 crop marketing year so far, but USDA’s outlook conference estimates show the gap narrowing for 2022.

Comparing these potential profits to acreage shifts suggests corn could add 575,000 to 1.215 million acres to USDA’s outlook guess of 92 million. Soybean losses could be less, from 45,000 to 265,000 of the February estimate of 88 million.

Fewer soybeans?

Good corn profits compared to soybeans can convince farmers to plant significantly fewer soybean acres than corn. USDA currently projects that percentage to be a little less than a year ago.

Whether those changes would be enough to sway prices depends on how old crop supply and demand play out in the second half of the marketing year that began March 1. USDA updates its forecasts for the world March 9, and may be cautious with so much uncertainty afoot. Trade estimates suggest 2021 crop corn ending stocks estimates could fall 75 million bushels, with soybeans dropping 50 million.

South American weather appears to be stabilizing, which could minimize further damage to soybeans there. But the fate of Brazil’s large second corn crop won’t be known until late spring and summer, further clouding potential export demand.

Argentina is already moving to restrict wheat exports as prices surge to 14-year highs, a rally that could also limit wheat feeding in the U.S. this summer. Wheat feeding slumped to just 16 million bushels in 2007-2008, the last time winter wheat futures hit double digits. USDA in February put feeding at 110 million bushels.

While sky-high gasoline prices could curtail driving – and the amount of ethanol needed for blending – the biofuel is more than competitive at current prices, which could encourage E15 and E85 usage. Data so far points to a 9% increase in corn used by plants, compared to the 6% bump over 2021 levels forecast last month by USDA, which would add 155 million bushels to demand.

Increased biodiesel consumption could also help soybean crush. USDA already forecasts a 24% rise in soybean-based biodiesel for the 2021 marketing year, though year-to-date crush is actually a little behind the 2020 crop season. Ukraine usually grabs about half the world’s sunflower oil market, helping give the vegetable oil complex another leg up that sent soybean oil futures to new all-time highs in Chicago last week.

Economics, however, are only one force influencing what farmers will actually plant. Springtime weather could scramble the best-laid plans of growers, or let them plant fencerow-to-fencerow.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like